In a summer replete with computer-hacking scandals — many of them at the hands of the collectives Anonymous and LulzSec — the adventures of Kevin Mitnick seem of a different time altogether.

In the early ’90s — the era of the primitive dial-up modem — the prodigious computer whiz used a combination of technical prowess and social trickery to hack into the servers of some of the world’s biggest companies. By convincing the unsuspecting that he was somebody else, he insinuated his way into valuable information, which he could then use to crack ostensibly impenetrable security systems. It’s a story that evokes the whimsy of “Catch Me If You Can” more than it does our traditional image of computer hackers — darkened silhouettes furiously typing in a dark basement, tired eyes affixed to a rapid scrawl of green characters across a half-dozen monitors.

Mitnick’s cyber-social acrobatics made him a hot target for the FBI, who pursued him for years. Only by assuming false identities and cleverly covering his tracks did he evade the authorities. He was finally arrested in 1995, and four years later he pleaded guilty to wire fraud, identity theft and computer fraud. Then came eight months in solitary confinement — he says because prosecutors convinced a judge that he could trigger a nuclear emergency by whistling into a phone.

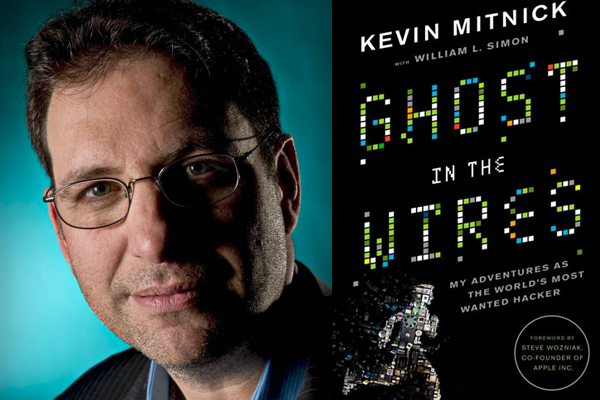

Under his parole agreement, Mitnick could not profit from his story in book or film form for seven years. Now, more than a decade after his release from prison, his memoir, “Ghost in the Wires,” (co-written with William Simon) is on bookshelves.

Salon spoke with Mitnick earlier this week to learn more about his story, his philosophy and his views on the modern hacker movement:

One of the things that fascinated people about your story was your social engineering — how you used your social savvy to convince people to give you the information you wanted. Was it easy for you?

It’s not so easy. When you’re doing these social engineering attacks, you have to be fast on your feet. You have to think about a story that’s going to be believable. You have to change people’s perceptions about what’s going on in the background to increase trust and credibility.

For example, when I’d be social engineering the phone company — when you’d call the business office at Pacific Telephone way back when, they’d give you advertisements instead of Muzak on hold. So, when I’d call these different phone company offices, I’d say, “Hold on for one second, I have another call coming in,” and I’d put them on hold and play the loop tape of their own advertisements. Then I’d come back on the line and start talking.

Immediately, subliminally, it seems like I’m really with the phone company, and I never said anything. It’s just using these types of techniques to build trust and credibility. I was really good at thinking how to do this. I was also really good at acting. I was able to develop the script on the fly. And that made me really successful.

Both social engineering and technical attacks played a big part in what I was able to do. It was a hybrid. I used social engineering when it was appropriate, and exploited technical vulnerabilities when it was appropriate.

How did you first get interested in this stuff? How’d you start developing your skill set?

The funny thing is, when I started hacking, it was a different era. In 1980 I was a senior in high school, and I tried to get into computer-science class. One of the first assignments was to write a program to find the first 100 Fibonacci numbers. I thought it would be cooler to get people’s passwords, so I wrote a program that simulated the computer system at school — when students would sign into the computer, they would actually be talking to my program, pretending to be the computer.

Because I was monkeying around with this program for so long, I didn’t get the assignment done. So, I showed the teacher my password-stealing program instead, and I actually got an A. He told the class how cool it was. And these were the ethics taught when I was growing up. Hacking was a cool thing, even stealing passwords. That was kind of how I started. Then, of course, the world changed around me.

I got so passionate about technology. Hacking to me was like a video game. It was about getting trophies. I just kept going on and on, despite all the trouble I was getting into, because I was hooked. I was addicted to hacking, more for the intellectual challenge, the curiosity, the seduction of adventure; not for stealing, or causing damage or writing computer viruses. This trend today of hacking to steal credit-card numbers has unfortunately changed the definition of what a hacker is today.

That actually segues into my next question, about Anonymous and LulzSec. Those two groups have garnered a lot of media attention for their exploits over the past several months. And I think what really interests people is how these groups combine high-minded activism with this puckish, pranky and arguably destructive approach.

I think what we have here is different factions: Because LulzSec became so popular — they got 300,000 Twitter followers and a highly trafficked website — they were kind of the pinnacle of civil disobedience. Originally maybe their motivation was to send a political message, that they were unhappy with Sony, that they were unhappy with the federal government.

What I think happened here was they got so much media attention and it bumped up their endorphin rush so much that they couldn’t resist. And I think there developed factions of Operation Anti-Sec [an ongoing collaboration between Anonymous and LulzSec] based on the media attention that LulzSec was getting. Everyone wanted to jump on the bandwagon.

Now it’s becoming more like cyber-extortion. There should be more socially acceptable ways for these guys to state their political messages. They used to just deface a website, but now its dropping “dox,” which means getting into a company’s internal sites and dropping confidential information.

And then you have kids who don’t know how to mask their identities attacking targets as part of the Anti-Sec movement, and they’re the ones getting arrested and prosecuted. The real guys behind this, I don’t think they’re getting prosecuted because they’re a little bit better at anonymizing their connection on the Internet.

You talk a lot in the book about how you felt that the legal system overreacted to your exploits.

It’s true, I had hacked into a lot of companies, and took copies of the source code to analyze it for security bugs. If I could locate security bugs, I could become better at hacking into their systems. It was all towards becoming a better hacker.

But the government’s theory — because they wanted to put me away for as long as possible — was that if I copied the source code to Solaris, for example, which was one of Sun’s flagship operating systems, that Sun lost their entire research and development investment in Solaris, which was millions and millions of dollars.

A good analogy is if I get caught stealing a can of Coke from 7-Eleven, and I get prosecuted for stealing Coca-Cola’s formula. It’s a big difference.

It wasn’t that I took the position that I didn’t deserve to be punished, or that I was doing the right thing. It’s my position that the harm was greatly exaggerated so that the government could send a message.

And do you think that kind of overreaction has instilled a misunderstanding about hacking within the general public?

Oh, yeah! A case in point with LulzSec: They did an attack against the CIA’s public facing website. This was low-tech stuff. A 15-year-old could do it. And then I get calls from the media, saying, “Oh, the CIA was hacked.” Which was a complete misunderstanding of what actually happened. The one news organization puts it on the Web, and then all the others follow along, and it snowballs into something crazy.

What do you think the danger in this is?

It’s the danger of informing the public incorrectly. Reporters don’t fact-check, or they want the sensational story, and they salivate when they hear that the CIA was hacked. “Ooh, what secret information did they get? What are they going to pass on to WikiLeaks?” (That was a serious hack. That was the No. 1 security failure of the USA, what Bradley Manning was able to do.)

But what happens is these misreported stories are repeated, and it just communicates inaccurate information to the public at large. I read an article about me today and it says, “In 1983, Kevin Mitnick hacked into NORAD.” And, in 1983, the movie “War Games” was released, about a character played by Matthew Broderick hacking into NORAD. Twenty years later it’s the same myth.