By delicious coincidence, the new movie "Rise of the Planet of the Apes" was showing in theaters nationwide, even as two contenders for the Republican presidential nomination debated whether it is a fact or a theory that humans, chimpanzees, gorillas, orangutans and gibbons descend from a common ancestor. On Thursday, Aug. 18, Jon Huntsman tweeted: "To be clear, I believe in evolution and trust scientists on global warming. Call me crazy." On the same day, campaigning in New Hampshire, Texas Gov. Rick Perry described evolution as "a theory that's out there" and one that's "got some gaps in it."

How times have changed. During his successful campaign for the presidency in 1912, Woodrow Wilson, Ph.D., the former president of Princeton University, was asked whether he believed in evolution. He replied, "that of course like every other man of intelligence and education I do believe in organic evolution. It surprises me that at this late date such questions should be raised." Theodore Roosevelt, his predecessor in the White House, wrote in "My Life as a Naturalist" about his childhood reading: "Thank Heaven, I sat at the feet of Darwin and Huxley."

The rise of creationist Protestant fundamentalism in America has been paralleled by the decay of liberal Protestantism, which supplied much of the moral energy for the progressive movement, the New Deal and the civil rights movement. For the most part, the liberal Protestant churches are losing members, not to more conservative denominations, but to a growing minority of the unchurched. Some are self-described atheists or agnostics while others profess a vague belief in God.

The religious vacuum to the left of center in the U.S. and Britain, where liberal Protestantism has undergone a similar collapse, has been filled with three new creeds. The first is radical environmentalism, which is best understood as a kind of nature-worshipping pantheism. The second is the "new atheism," with champions like Richard Dawkins and Sam Harris. The militantly anticlerical tone of the new atheism is not particularly new; it differs little from that espoused from the 1960s to '80s by the late Madalyn Murray O’Hare of the American Atheists Association.

The third and perhaps hardiest creed, now nearly a half-century old, is "secular humanism." With less fanfare and more tact than the new atheists, "secular humanists" have attempted to provide an all-encompassing public philosophy based on science, as an alternative to moralities and political programs justified by supernatural religion. While the scientific naturalism that inspires it is true, American "secular humanism" is a naive and sentimental creed that, ironically, is too unworldly to serve as a practical guide to ethics and politics on this, the real planet of the apes.

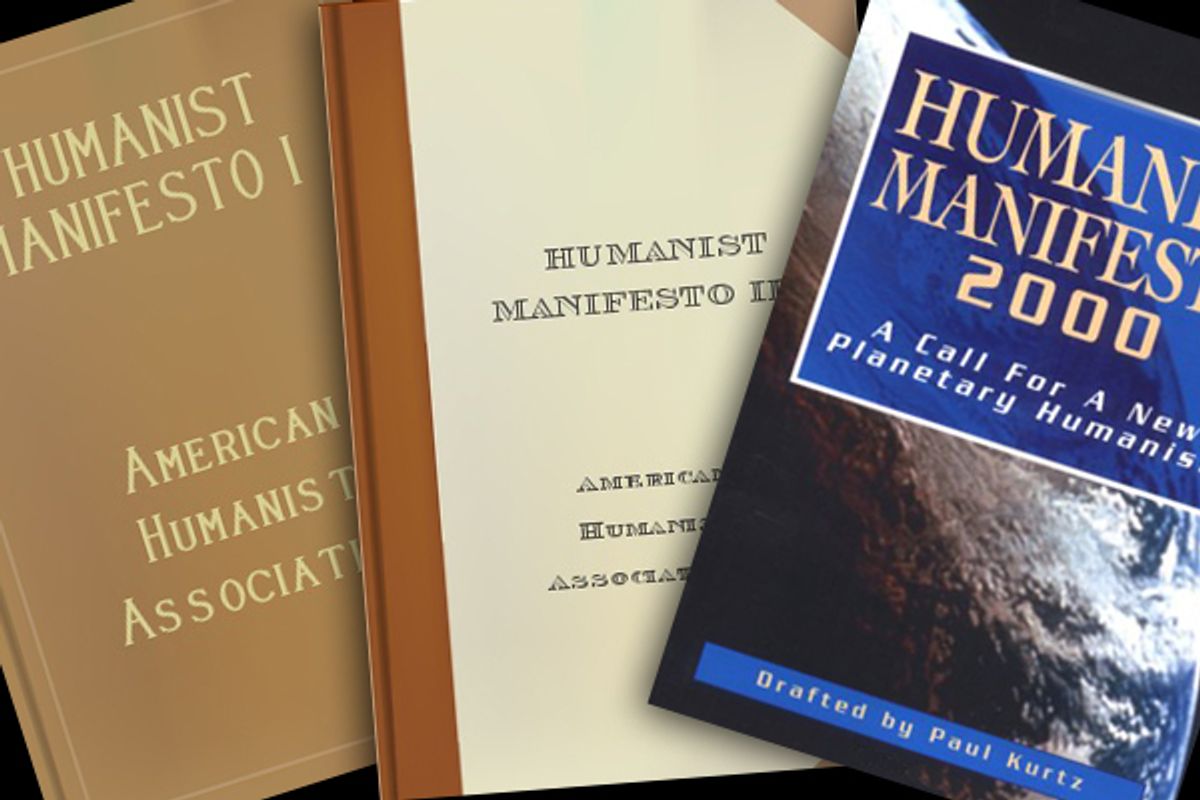

The equivalent of the Nicene Creed for secular humanists is the "Humanist Manifesto," published in 1933. Signed by the philosopher John Dewey and a number of now-forgotten professors and clerics, it called for a "religious humanism."

In 1973, Paul Kurtz, a professor of philosophy who has taught at the State University of New York at Buffalo, co-authored second humanist manifesto. In 2003 the American Humanist Association, of which Kurtz is a member, published a third update, titled "Humanism and Its Aspirations."

Kurtz also published a book with the title "Humanist Manifesto 2000: A Call for a New Planetary Humanism."

Since then, he has published yet another manifesto, titled "Neo-Humanist statement of secular principles and values: Personal, Progressive, and Planetary."

If the secular humanist creed lasts a millennium, it may well generate more manifestos than the pope has encyclicals.

Kurtz’s call for planetary humanism in 2000 is representative of this ramifying literature. Notwithstanding conservatives who claim that secular humanists are relativists, humanists of the Kurtz school are defenders of the Enlightenment and hostile to postmodern intellectual and moral relativism. The call for planetary humanism begins with a strong and, to my mind, entirely persuasive defense of science ("a coherent world view disentangled from metaphysics or theology") and technology (which can "advance happiness and freedom, and enhance human life for all people"). Philosophers from Francis Bacon to John Dewey, the manifesto notes, "have emphasized the increased power over nature that scientific knowledge affords and how it can contribute immeasurably to human advancement and happiness."

Hear, hear! I am not particularly fond of Dewey, but any friend of Francis Bacon is a friend of mine.

Unfortunately, in the next section Kurtz’s secular humanist manifesto addresses "ethics and reason" and goes horribly wrong, never to recover:

The realization of the highest ethical values is essential to the humanist outlook. We believe that growth of scientific knowledge will enable humans to make wiser choices. In this way there is no impenetrable wall between fact and value, is and ought. Using reason and cognition will better enable us to appraise our values in the light of evidence and by their consequences.

Here Kurtz implicitly takes on another atheist, the 18th century Scottish philosopher David Hume. Hume famously wrote that you cannot derive a moral "ought" from a factual "is." He also insited that, "Reason is, and ought only to be, the slave of the passions." By this Hume meant that reason by itself cannot supply motivation. Reason is like the GPS device in a car. Emotion can tell reason where to go, and reason can tell emotion how best to get there. But reason itself is a neutral instrument, which can aid sociopathic murderers and genocidal tyrants as well as saints and heroes. If Hume’s version of atheism is correct, then the entire secular humanist liberal project in its current form is fundamentally misguided.

Unlike Hume, Kurtz dismisses any barrier between "fact and value, is and ought." According to Kurtz, "The realization of the highest ethical values is essential to the humanist outlook." How do we distinguish among higher and lower values, he asks? "Using reason and cognition will better enable us to appraise our values in the light of evidence and by their consequences." In other words, we will ask the car’s GPS computer to tell us not only how to get there but also where we should go.

Our moral GPS, it seems, has software written by the 19th century utilitarian philosopher Jeremy Bentham. That, at least, is implied by Kurtz’s allusion to "the consequences" of our "values." Consequentialism is another name for utilitarianism, the goal of which is to promote "the greatest good of the greatest number." Utilitarianism tends to be cosmopolitan in its scope. After all, if what is good for a nation is more important than what is good for a family, surely the greatest good, the secular summum bonum, is the good of the human race.

Sure enough, in the next sections of his manifesto Kurtz proceeds from suggesting an ethic of utilitarianism to calling for cosmopolitan ethics and politics, including "a Universal Commitment to Humanity as a Whole," "a Planetary Bill of Rights and Responsibilities," and a "New Global Agenda." The conspiracy theorists of the far right are wrong when they accuse secular humanists of moral relativism -- but at least some secular humanists like Kurtz really do believe in world government.

He asserts "The Need for New Planetary Institutions," including

A bicameral legislature in the United Nations, with a World Parliament elected by the people, an income tax to help the underdeveloped countries, the end of the veto in the Security Council, an environmental agency, and a world court with powers of enforcement.

In calling for a World Parliament and a global income tax, Kurtz has forgotten or neglected the warning found in the 11th clause of the original 1933 Humanist Manifesto:

We assume that humanism will take the path of social and mental hygiene and discourage sentimental and unreal hopes and wishful thinking.

Paul Kurtz doesn’t speak for all secular humanists, of course. And the themes of secular humanism have varied somewhat in the last century, reflecting the intellectual fashions of the left-liberal intelligentsia. In the 1930s, liberals tended to favor economic planning and democratic socialism, so the first Humanist Manifesto claimed that scientific naturalism required the socialization of the economy, because

existing acquisitive and profit-motivated society has shown itself to be inadequate and that a radical change in methods, controls, and motives must be instituted. A socialized and cooperative economic order must be established to the end that the equitable distribution of the means of life be possible.

A vague environmentalism has replaced equally vague visions of democratic socialism as the leading source of moral fervor on the center-left. In the recent humanist manifestos we hear about duties to nature rather than the need for socialism. In Kurtz’s words we have "a planetary duty to protect nature’s integrity, diversity, and beauty in a secure, sustainable manner."

For all the variations, the common theory of human nature underlying contemporary secular humanism seems to be cosmopolitan utilitarianism, the conviction that human beings, if liberated from superstition by science, would behave less like selfish, scheming social apes and more like self-sacrificing social insects, giving their all for the good of the 7 billion members of the global human hive. "Life’s fulfillment emerges from individual participation in the service of human ideals…" says Humanist Manifesto III. "Working to benefit society maximizes individual happiness."

The secular humanist movement avoids the difficult question of the coexistence of in-group altruism and inter-group rivalries by imagining, with John Lennon, that conflicts would vanish if only people stopped being religious and patriotic.

Imagine there's [sic] no countries

It isn't hard to do

Nothing to kill or die for

And no religion too

Imagine all the people

Living life in peace

Unfortunately for Humanist Lennonism, evolutionary biology does not provide much hope for the sort of altruistic personal commitment to planetary solidarity that secular humanists want to encourage. Humanist Manifesto III claims that the joy in Stakhanovite that enlightened human beings liberated from religion are expected to feel -- an "ought" -- can be derived from an "is" -- biological fact. "Humans are social by nature and find meaning in relationships."

But social animals are not altruists. Nor are they strict individualists. They are nepotists. As a rule social animals, like wolves, deer, humans and chimps, show favoritism to their relatives and friends and allies, with little or no concern for members of their own species with whom they have no close connection. Abrahamic monotheism insists on the brotherhood of man under the fatherhood of God. Darwinism insists at best on the distant cousinhood of humanity.

Among humans, nepotistic solidarity can be transferred, with difficulty, to political units larger than the extended family. But national patriotism is much harder to promote than city-state patriotism, and global patriotism may be a bridge too far.

The illogical leap from the acceptance of evolutionary science to the call for world government and world taxation is typical of the intellectual legerdemain practiced by secular humanists. They assert scientific naturalism leads to the currently fashionable attitudes of North Atlantic left-liberals, but they never provide any convincing arguments for the thesis that if you believe in Darwin, you must follow Dewey.

Let it be stipulated that, because they rested on economic or racial pseudoscience, Marxism-Leninism and National Socialism need not be taken seriously as variants of secularism. But what about the right-wing secularism of Ayn Rand? What do militant atheists who favor socialized medicine and world government have to say to other militant atheists who follow Rand in wanting to substitute the dollar sign for the cross and celebrate unregulated capitalism? For that matter, what would conventional secular humanist liberals have to say to an intelligent, thoughtful, scientifically literate, secular authoritarian -- say, the late German jurist Carl Schmitt or Dostoyevsky’s Grand Inquisitor?

Given the fact that there are secular conservatives, secular libertarians and secular authoritarians, as well as secular liberals, what conclusions, if any, for politics and economics follow from the scientific account of nature? I don’t pretend to know. I suspect that scientific naturalism, properly understood, provides more warnings than answers.

To the extent that natural science can inform the way we think about politics and economics, it undermines the view that human beings are, or could be, rational actors devoted to the common good, rather than emotion-driven, semi-rational cousins of chimps and gorillas. On this point the secular philosophers Hume and Hobbes are more convincing than Bentham, Dewey and Kurtz.

Our simian psychology has obvious implications for naive models of democracy, in which a neutral, rational public listens dispassionately to all sides before making up its hyperlogical collective mind. And it has implications as well for naive models of economics, in which consumers and producers perceive, think and act with computer-like accuracy.

The skepticism about human rationality that science inspires should not be taken as support for authoritarianism or paternalism (sorry, Professor Schmitt and Your Eminence). On the contrary, it should render questionable all claims to wise and disinterested leadership, including those of America’s own altruistic progressive technocrats who propose policies to "nudge" the unenlightened masses into doing the right thing. It makes more sense to think of our leaders and intellectuals as half-crazed hooting howler monkeys -- just like the rest of us.

Science can tell monkeys where they came from, and technology, informed by science, can build a cleaner and safer monkey house. But a knowledge of science cannot turn monkeys into something that we are not.

Shares