My own mother, my sister and nearly all the women in my family had full-time jobs as mothers. They were wonderful at it. They drove their children back and forth to soccer, skating lessons, piano lessons, private schools, but I sensed, even in my own mother, a kind of distant dissatisfaction.

Every time I went to the doctor when I was in my twenties, he repeated the same thing to me: don’t wait too long to have children. But since then I had spent nearly two decades as a war correspondent seeing children wrecked and traumatized by war. I saw babies born in the middle of a siege, saw amputated limbs, kids who stepped on landmines, a young swimmer who lost her breast to shrapnel, budding nine-year-old soccer players who lost their hands to American smart bombs, kids who had breakdowns, kids who were blown up by mortars as they were building snowmen.

I saw kids orphaned from AIDS in Africa and India, and I held them and fantasized about bringing them away with me and giving them a home and food and real medical treatment, but the fact was, I was not entirely sure I — who could barely take care of myself unless it was in the midst of chaos — could care for them. And seeing all of that, as much as I protested that it had done nothing to me, alienated me from people who had never seen it at all. When I returned to London from my assignments, the only people I wanted to see were people I did not have to explain anything to, people who did not ask questions, people who had seen what I had seen. And my husband, Bruno, a French news cameraman who knew me, who understood me and who spoke a language identical to mine.

I played Russian roulette with my biological clock, and then when the time came and I felt capable of becoming a mother, it was almost too late. I got pregnant very easily. But the weeks would pass, I would buy special oil to rub on my belly for stretch marks, and maternity dresses, and then one night I would wake up in agonizing pain and get rushed to the hospital, and a grim-faced nurse or doctor would tell me the baby was dead.

No one could work out what was happening, why my body kept failing me, and I spent what seemed like months inside the labs of St. Mary’s Hospital, Paddington, having blood test after blood test. Finally, someone, a doctor in New York worked it out: my niece and my mother suffered from a rare blood-clotting disorder, and one day, I found out I had the same thing. But it took years to discover, and years for this baby to come down to earth.

In the Bible, both Sarah and Rachel, who had very late and very yearned-for babies, are told that the child who is much desired, much waited for, is always special. And I had waited so very long for my Luca.

When I finally held him firmly inside me, I tried to act appropriately: I thumbed through my copy of “What to Expect When You’re Expecting,” but I only got through the first chapter. Nothing in it seemed to relate to me. Someone loaned me a Moses basket with long handles so I could carry the baby everywhere, which was my plan. When people asked what I would do about work, I would shrug and say I would take the baby with me in the basket. In truth, I had no clue what I would do or how I would manage my life.

When my boss, a man with many children, found out I was pregnant, he brought me into a small office, his face full of anger. “I’ve got a war correspondent who can’t go to war,” he said. “I’m allowed to get pregnant, aren’t I?” I responded, but he talked about contracts, and Iraq, and maternity leave and getting back to work, and I knew then that I could never do it again, not the way I had before. I knew that I would miss reporting the war that was breaking out in Baghdad, in Basra, in Mosul, but I realized for the first time I had made a choice, and that I had to stand by it.

He finally stopped talking, still angry, and I sat in my chair, slightly dazed. I’m not sure I knew then how deeply the addictions of being in those places, those times, watching countries fall apart and being put back together again, had affected me.

A specialist in post-traumatic stress disorder, which I had been tested for extensively in the 1990s by a Canadian psychiatrist writing a book about war reporters, said I did not have it. Aside from one brutal flashback after the murder of two of my colleagues in Sierra Leone by rebel forces, and weeks of seeing people amputated at the wrist or the elbow, I managed, somehow, to escape a syndrome with which so many of my colleagues had been afflicted. At one point, a psychiatrist in Sarajevo told me that nearly the entire population of the besieged city probably suffered from it.

I had never had nightmares in the years of moving from war to war — perhaps some inner survival mode would not allow me to be introspective enough to see it — but they started now: vivid dreams of burning houses, of people without limbs, of children trapped inside shelters. I thought endlessly of the days in Chechnya when I listened to the helicopter gunships and put my hands over my ears, sure I would go mad from the sound of the bombs. Or the time that I rode on the back of a motorcycle in East Timor and smelled the burning of the houses, saw the terror in people’s faces.

Every time something terrible happened to me, Bruno was there to save me. In January 2000, I had gone to Chechnya, knowing what I would find: a brutal war, perhaps worse than what I knew in Bosnia. We were caught in a suburb with the retreating Chechens, who were covered in blood from crossing a minefield to get out. I stood in a freezing school building with my feet sticking to blood on the floor as the lone doctor chopped off limbs with minimal anaesthetic, and I saw the men’s eyes open on the table, bracing themselves against the saw.

That night, I gathered with the soldiers in a small wooden house and we told jokes, but there was nothing to joke about. The Russians were circling the village with tanks; by daybreak they would enter and probably waste everything in sight, the way they had wasted villages like Shamaski, nearby,when special forces went in high on drugs and killed and killed and killed.

I was there illegally, without a work permit, without a Russian visa, and there were no aid workers, no UN peacekeepers, no Médicins Sans Frontières. There were Thomas, a German photographer, and me, and earlier I had met a French reporter dressed as a Chechen woman, but that was it. There was no way for us to leave the village, and the shelling that was raining down on us was heavy.

Back in the house with the other soldiers, we ate pickled cabbage from a jar an old woman had given us, and bread. I sat on a bench with my arms wrapped around myself from the bitter cold and thought, All right, this is it. This is really the end. With the last battery of my satellite phone and no electricity, I filed my story: Grozny had fallen to Russian forces. Then I called Bruno. “I can’t get out. I’m trapped here.”

“Listen,” he told me in the calmest voice, “I can’t do anything for you from here. No one can, do you understand? But you have to get out of there, somehow. Find a way to leave that village, don’t stay with the soldiers any more. And don’t be scared. You are going to live. You have angels all around you.” Then he hung up, telling me that saving batteries was more important. “I’ll see you soon — do you understand? Now get out of there, fast.”

I stood with the receiver in my hand, and disconnected my satellite phone. I spent all night in the potato cellar with the old woman while the shells fell, and then in the morning light, I saw the soldiers retreating in a long column, some angry, some throwing their guns in the snow, dragging the dead. There was so much blood in the snow.

An hour later, the man from Ingushetia who had brought us into Chechnya drove into the compound in an old car. “Get in, get in,” he shouted. “Now!” He had bribed the Russians to get through. The old woman dressed me like a Chechen, and someone handed me a baby for me to smuggle out. “Not a word,” the driver said. “You’re a deaf mute. This is your baby. We’re leaving.”

On the way out, we wove through the tanks and he handed each crew money. When we got to the road, he broke into breakneck speed and told me, ridiculously, to put my seat belt on. The baby did not cry at all. I turned to look at the village one last time and saw the tanks moving in.

We found refuge in another village that seemed safe, but which got rocketed a day after we arrived, killing schoolchildren I had seen earlier, walking in the snow with little backpacks. From there, I phoned Bruno.

“I knew you would live,” he told me. “The best reporter is the one who gets out to tell the story. And also,” he added, “there are the angels.”

Then, and later, I felt nothing. I never talked about what happened in those places, but I wrote about them. I disagreed that reporters suffered from trauma; after all, I argued, we were the ones who got out. It was the people we left behind that suffered, that died. I did not suffer the syndromes, I did not have the shakes. I did not have psychotic tendencies. I was not an alcoholic or drug addict who needed to blot out memories. I was, I thought, perfectly fine and functioning.

Much later I met another trauma specialist in a café in London. He told me that PTSD can also appear later, long after the events. He asked me to describe all I had seen, in detail, but nothing was as painful as Luca’s birth: the helplessness, my inability to protect him, and the sense that anything could and would happen. He listened carefully, wrote everything in a notebook and recorded my words, which he later sent to me in transcript form. “There are people who live in extremes,” he said, “and you are one of them. You cannot think that will not affect you in some way. It has. It always will.”

The birth awakened fears that had been buried. It started when I hoarded water in our Paris kitchen: plastic packs of more than fifty bottles, which I calculated would last us twenty days. Every time I went to Monoprix, the French department store, to buy food, I bought more and had them delivered. I hoarded tinned food, rice, pasta — food that I remembered stored well in Sarajevo during the siege — and things that might be hard to get — medicine, vast supplies of Ciprofloxacin and codeine — which I got my confused doctor to give me prescriptions for. I hoarded bandages, gauzes, even the brown-packeted field dressings that I had saved from Chechnya which were meant to be pressed against bullet holes to staunch the blood, and I read first aid guides of how to remove bullets and shrapnel, set broken bones and survive chemical attacks. Bruno would watch, concerned but non-judgmental.

“We’re in Paris,” he would say, “not Grozny. Not Abidjan. We’re safe.”

“But how do you know? That’s what people said about Yugoslavia. One day they went to the cash machines and there was no money.”

I began to hide cash around the house and took copies of our passports. I made lists of what I would grab if we had to flee, and I made Bruno make an exit plan if we had to leave Paris in an instant. Where would we meet? How would we get out? I read books about people escaping from Paris after the Germans arrived, and discovered the route was through Porte d’Orléans.

Bruno finally said, “Maybe you should talk to someone about this?”

But it was all about the baby. If I was alone and caught in a terrorist attack, or a flood, or a disaster, I could manage. But I was terrified of being alone with my son if something major hit and I had to protect him. I was convinced I could kill someone who tried to harm him, and the knowledge of that darkness inside myself frightened me. Everyone on the street I saw as potentially dangerous, and when I walked down the road, I felt invisible, like a ghost, even in the brightest Paris daylight.

I knew I had to fight it. I began to strap the baby onto my chest with the kangaroo holder, and walk. I desperately wanted to feel at home, at ease, and I wanted to try to make this city — where everyone buzzed around so quickly and knocked into you with their skinny elbows — my home.

But I often felt as though I was in exile. One day I realized that war, with all its dangers, seemed utterly normal to me. My real life, my story with Bruno, was behind closed doors in some conflict zone, safe from everything else, where we created our own history. It was what I understood about him best of all: falling in love in chaos.

This real life, with all its sharp edges, was terribly difficult.

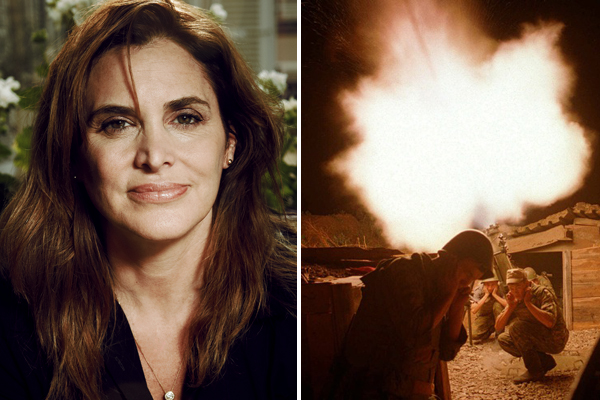

Janine di Giovanni has won four major journalistic awards, including the National Magazine Award, and is a contributing editor to Vanity Fair. She is the author of “Madness Visible,” “The Quick and the Dead” and “The Place at the End of the World.” She lives in Paris.

Excerpted from “Ghosts by Daylight” by Janine di Giovanni. Copyright © 2011 by Janine di Giovanni. Excerpted by permission of Knopf, a division of Random House, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.