Let me tell you a story about the history of America. About drunken physicists, the atom bomb and the greatest cheeseburger in the world.

At 5:30 a.m., July the 16th, 1945, the United States detonated the world’s first implosion-design plutonium bomb. Wise or not, it did this thing in the middle of a desolate, dry and beautiful stretch of hell outside of Socorro, New Mexico, called the Jornada del Muerto — the Route of the Dead Man.

At 5:30 a.m., July the 16th, 1945, the United States detonated the world’s first implosion-design plutonium bomb. Wise or not, it did this thing in the middle of a desolate, dry and beautiful stretch of hell outside of Socorro, New Mexico, called the Jornada del Muerto — the Route of the Dead Man.

There were 240 people who knew about the first test; 239 of them were scientists or military personnel, high-ranking political figures, generals, and the President of the United States. One of them was grocer and a cook: J.E. Miera, the only civilian to see the flash, the boom, the tremulous mushroom cloud rising against the dawn sky, and know it for what it was. He stood at the crossroads of Second Street and old U.S. Highway 85 — the only two roads of note in the flyspeck town of San Antonio, New Mexico — and alongside some of those soldiers, some of those scientists, he watched history being born under the umbrella of light.

When that was done, he went inside. At some point, he and his son, Frank J. Chavez — owner of the Owl Bar, which sat in the lot beside Miera’s small grocery store and row of cabins — started popping beers and making cheeseburgers.

Find me out at the bar some evening — propping up the long oak with a head full of Irish brain lubricant and a glass of dry rocks in front of me. Sit down on the next stool with a full wallet and some time to kill, and this is the story I’ll tell you. It’s my hands-down favorite food story ever. The one that has gotten me more free drinks than any other I know.

Miera had been running his store and renting out his cabins in San Antonio since 1939, in competition with the only other business of note in town: the A.H. Hilton Mercantile and Hotel — the first business venture of the family that would someday be known mostly for the unfortunate production of Paris Hilton.

But it was a fight that Miera was winning, because his place? It had the only phone in town. The only gas pumps, too. And when A.H.’s place burned to the ground in 1940, Miera ended up with something else as well: Hilton’s wooden bar, which he’d rescued from the wreckage and hung onto, thinking that, someday, he might need it.

Come 1945, he did. Or rather, his son did. Because in 1945, Miera was playing host to a bunch of “prospectors” who were renting out all his cabins, buying up all his gas and tying up his phone at all hours. These men claimed that they were rock hounds — mineral enthusiasts who spent their days out in the middle of nowhere, and their nights in San Antonio because San Antonio was just to the left of the middle of nowhere.

Of course, those prospectors? They weren’t really prospectors. They were Robert Oppenheimer’s atomic cowboys, the sunburned physics geeks and Wild West Poindexters of the Manhattan Project who would shortly be giving birth to their own small, hot high desert sun. When Frank Chavez came back from the war, the scientists were already in San Antonio. Looking at his father’s inn, he realized they had a phone. They had gas for their jeeps. They had a roof over their heads. What Frank figured they needed now was beer.

So he built his roadhouse and called it the Owl. At the center of it, he installed Hilton’s bar, put the beers on ice and started serving. Shortly after that, what he figured his best, most dependable customers needed were cheeseburgers. Green chile cheeseburgers. Lots and lots of green chile cheeseburgers.

Actually, it seems more likely that Frank was asked to start making cheeseburgers. The story goes a few different ways: That it was Frank’s idea alone, that it was a request from one of the MP’s who’d begun to filter into town — a man late of California where both the cheeseburger and the green chile were already close friends — or that it was an order, coming down direct from someone at Los Alamos, where the Manhattan Project was headquartered. It’s the third version that carries weight with me. The notion of Uncle Sam, Harry Truman and Robert Oppenheimer demanding cheeseburgers to fuel the midnight genius of these odd and sunburned nerds just moves me. And it makes sense, too. It had to occur to someone, somewhere, that having the best brains in America getting all liquored up and tear-assing across the desert in the middle of the night looking for tacos was just a phenomenally bad idea. Eventually, one of these guys was doubtless going to wrap himself around a cactus at 60 miles an hour. And it’d be a shame, too, because there just weren’t any tacos to be had anyway.

Frank installed a grill and started making cheeseburgers topped with roasted and chopped green chiles from Hatch and Socorro and Magdalena. And every night at the Owl’s bar, some of the smartest men in the world sat through the huge New Mexico nights, drinking cold beer and eating burgers, burning their tongues on sweet-hot New World chiles while talking about implosion triggers, explosive lensing and, among themselves, laying bets on what would happen when “The Gadget” was finally detonated. There were pools, with results ranging from a complete dud, to destruction of the state of New Mexico, to ignition of the earth’s atmosphere and the subsequent death of every single living thing in a fireball like the bright bloom of a match head.

“Like a match head,” I would say, snapping my fingers. “Like a wooden match. No one really thought this was likely, but it was a possibility, you understand? These guys, they thought that there was a chance — remote, but still. A chance that their toy would destroy the planet. Did it stop ‘em? No, it did not.”

This is how my story goes — spinning out easy over drinks, which, at this point, you are buying. I’ll sip mine, tap my knuckles on the bar, continue. “The betting pools, they were going on at the Owl — at Frank’s bar, at the tables, out in front of J.E.’s cabins with the stars clear as ice chips overhead. Guy who won it was I.I. Rabi, a Nobel Prize-winning physicist. He picked 18 kilotons, but he did it by default: It was one of the only options left; he picked late. He was around Los Alamos and San Antonio during the last days before the test. The Army brought him in because he was a friend of Oppenheimer’s and they thought that Oppenheimer needed a friend to keep him from losing his mind.”

July came and things in the Jornada del Muerto were getting weird. Locals, ranchers, desert rats — they were telling stories about a big tower being built out in the sands, about bunkers and blockhouses of poured cement sprouting like string warts on the land.

On the night of July 15th, a couple of MP’s were hanging around Miera’s property. These were probably guys that he knew — customers at his grocery, regulars at Frank’s bar. At some point, they took J.E. aside and whispered in his ear — telling him that if he wanted to see something pretty goddamn cool, he ought to haul himself out of bed real early in the morning, about 5:30 a.m. Go stand in the street, they would’ve told him. Look out toward the horizon. Just wait.

And J.E. did. He didn’t tell his family about it. He didn’t tell anyone. But he stood there — him and a handful of soldiers and scientists who didn’t have anywhere else to be — and they all looked out across the twenty-odd unobstructed miles between the Owl Bar’s front door and the Trinity site. At 5:29:45, the bomb went off. The cloud rose to almost eight miles. The explosion was felt a hundred miles away.

“My grandma, she thought it was the end of the world,” Rowena Baca told me a half century later, laughing about it. She is Frank’s daughter, granddaughter of J.E. Miera. She was a child in 1945. (“Little,” she tells me. “You don’t ask a woman her age.”) And today, along with her husband, Adolph, she runs the Owl Bar & Café like her father did before her.

“I’ll never forget that. Everything shook. She shoved us under the bed because that’s what you used to do, right? No one knew any better. And then the whole world just turned red.”

That was the way the world ended. That was the way it began again — all on a July morning in 1945. Frank would continue popping the tops on long necks and grilling cheeseburgers long after Oppenheimer and his prospectors vacated the region, serving the locals now, the farmers and the ranchers. And the story would end there — a strange historical curiosity of atomic bombs and cheeseburgers — if not for one thing. The Owl Bar made the best cheeseburgers in the world.

Made then, makes now. Hands-down. There are a lot of people out there who will tell you that the best cheeseburger in the world is made somewhere else, but they are all wrong. The Owl Bar makes not only the most important cheeseburgers in history (and makes them under Rowena’s ownership in exactly the way it did under Frank’s), but also the best you will ever have.

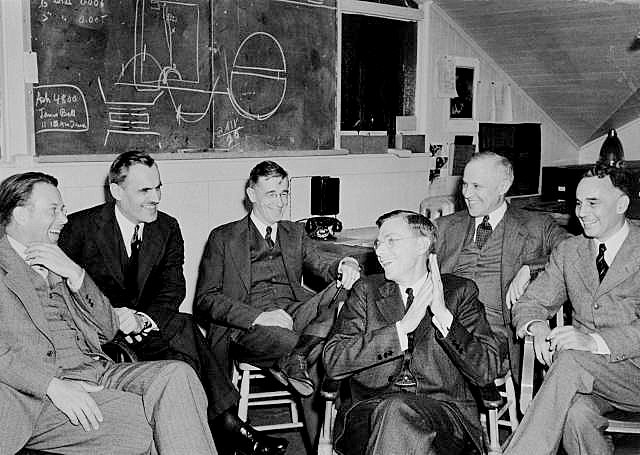

If you go — when you go, to sit among the sun-dried locals, bikers, families and atomic-age tourists melting in the white heat, to look around and see the history climbing the walls in yellowed newspaper clippings and black-and-white photos of skinny gringos packing slide rules and plotting terrible things — order the green chile cheeseburger. It’s a thin patty, hand-formed from fresh ground beef, topped with cheese, chopped lettuce and roasted, chopped Hatch and Luna County green chiles. Smoky-hot, sweet, tender and messy all at the same time, it’s a burger worth lingering over; that has been perfected across the decades by a kitchen that doesn’t do much else.

The Owl is an easy place to find. Just go to the absolute middle of nowhere and turn left. You can’t miss it. And when you come back — wild-eyed, altered, changed, inevitably, by the chiles and the huge, unforgiving sky that once felt the heat of two rising suns — you can tell me whether or not it was worth the price of the couple drinks you bought me, the hour of your time.

I’ll be at the bar, waiting.