Ping! The other day, I got a Facebook friend request in my in box. This is now a relatively rare occurrence – I’m long past the frenzy of those first few Facebook months when friend-finding was more satisfying and addictive than chocolate, and I’m done gorging myself on it all. But, intrigued, I opened it up, to find that this was no ordinary future friend (from the past) – it was a man I’d met while making a film about a tribe from the Sepik Valley in Papua New Guinea. It was a man who was born and raised in a remote hunter-gatherer society, where, to this day, the women spend their time searching out wild sago palms in the swamps to pulp into flour for pancakes, and the men hunt monstrous saltwater crocodiles in tea-colored jungle rivers at night with nothing more than spears. My new Facebook friend no longer joins these hunts – he’s an elder and has managed to find some income in the embryonic Sepik tourist industry – but for many years he was a hunter-gatherer, and now he’s on Facebook!

Of course I accepted the request and was immediately gifted an entrance ticket to a remarkable corner of Facebook – a place where friends comment upon each other’s walls in Papua New Guinea’s wonderful lingua franca, Tok Pisin (a language that started life as a pidgin and is just about translatable if you say it out loud), tag each other in photos of their relatives’ scarification ceremonies (the most disturbing albums you’ll ever spy on Facebook), and post each other links of mining companies’ press announcements (so that they can challenge the frequent ambitions of multinationals to ruin their homeland).

I’ve long since ceased to view the cultures of the Sepik tribes with the romantic and naive preconceptions that we in the West routinely assign to hunter-gatherer societies. I know, from having lived with these people in their magnificent A-frame stilt houses, that Sepik tribes are as modern a group of people as any of us – people who, like you and me, must constantly interrogate and adapt the culture they have inherited so that it best suits the changing world about them. But even I was astonished to discover that a community that only recently learned that arrows could fly better if they had feathers on their shafts was now into Facebook.

I’m not being flippant. I was actually in the room when members of the “Insect Tribe” became the first people from the Sepik Valley to discover the “feathers on arrows” idea. In fact, I was the one who inadvertently introduced them to it in the hall of a community center in Weston-Super-Mare, England. I’d better explain.

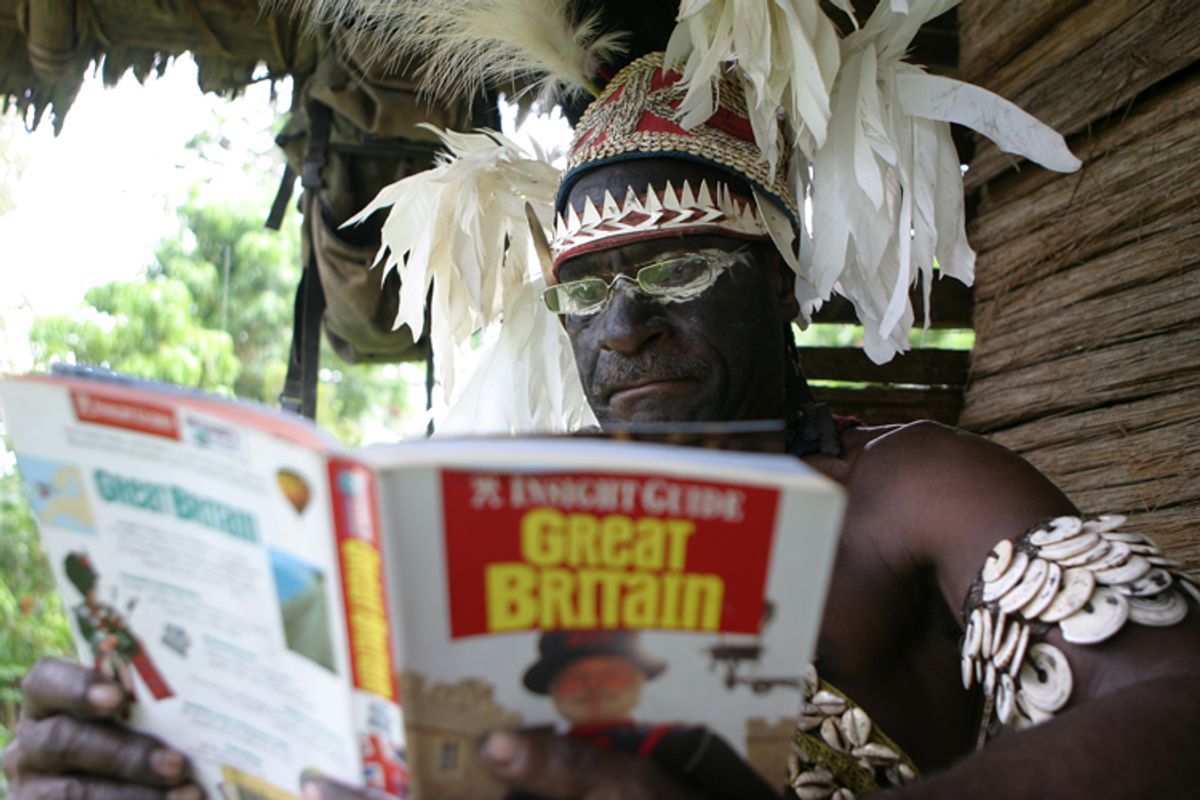

The previous year, the television company I worked for had made the typical documentary where an adventurous Western presenter goes out to visit a tribe in a remote part of the world to see how they live. While there, the crew had been approached by their hosts, the Insect Tribe, to see if it would be possible for the reverse journey to take place – for members of the tribe to go on an adventure to a remote part of the world to examine an equally strange culture – ours. “After all,” they had said, “your queen is our queen, our chief. Why shouldn’t we come to visit her territory?”

The company I worked for didn’t have a good reason why they could not, so we pitched it as an idea and got it commissioned. That’s when I was brought in. Worried that their visit might pollute their culture with modern ideas, or perhaps make them terminally envious of a world beyond their reach, I talked to some experts on Papua New Guinean tribes, and at that point exposed myself for the blinkered bigot that I was. “How dare you,” said one anthropologist, “to imagine, without question, that a Sepik tribesman would be envious of your culture. That’s one of the most arrogant things I’ve ever heard. These people are supremely proud of their own culture. They have a much more rewarding lifestyle than the majority in the West. Mark my word, they won’t want anything you can give them.”

And, essentially, she was right. Six members of the tribe came to Britain. With every whispered observation, they left us powerless to explain the madness of our own social norms, and when they boarded the plane back to PNG, we were the ones racked with envy – envious of their joyously interdependent community, their clear understanding of what mattered in life, their rock-solid roles, simple pleasures and ample leisure time, their lack of mortgages and debts, their indisputable “goodness.” Our world appeared an obscene and dysfunctional manifestation of human existence in comparison.

But the anthropologist was wrong about one thing; they did take something back: the idea of putting feathers on arrows. In the second week of their visit, I took three of the tribe to watch an archery club shoot at targets in a local community center. One of the archers was a fanatic and made his own arrows from willow, spruced with turkey feathers. The tribesmen were fixated on the feathers. “Why these feathers?” they asked. “It makes them fly straight,” said the enthusiast. And after a few practice shots, the tribesmen discovered that it certainly did. Their eyes lit up. Back home (presumably for thousands of years), they had been making arrows that were three times the size and weight of these feathered arrows, because without feathers an arrow needs to be weighty in order to fly true through the air. Just adding feathers would mean that they could carry three times the number of arrows out on hunts, and shoot three times the number of feral pigs. Of all the ideas in England, this was the one that could have an immediate and significant impact on their lives.

But since then, they seem to have taken up Facebook too. Why, after rejecting all those wonderful English ideas, did Facebook cut through? The answer must be that they are attracted to Facebook for the same reason that all of us are. Our species is universally addicted to sharing information. We will gobble up any technology that enables one human to communicate with another, be it a hollow-log-and-stick or social media – after all, it’s all more moreish than chocolate. Now Facebook is here, we shouldn’t be surprised that hunter-gatherers will want to log in too.

But, what I am here to tell you is that it’s happening now. We now live in a world in which a tribe that had not even heard of a feathered arrow until two years ago, can access every idea in the world. For the first time in history, humanity is truly open-access. Our entire species is “logged in.” Should we mourn the passing of a phase in our history when bands of human minds still lived in isolation, or rejoice that we are finally all on the same page? I’m not really sure, but I do know one thing – it’s time we updated our status.

Jonnie Hughes is an award-wining documentary-maker and science writer from England. His latest book, "On the Origin of Tepees," looks at how ideas can be considered to have a life of their own, with their own evolution, natural history and "survival of the fittest."

Shares