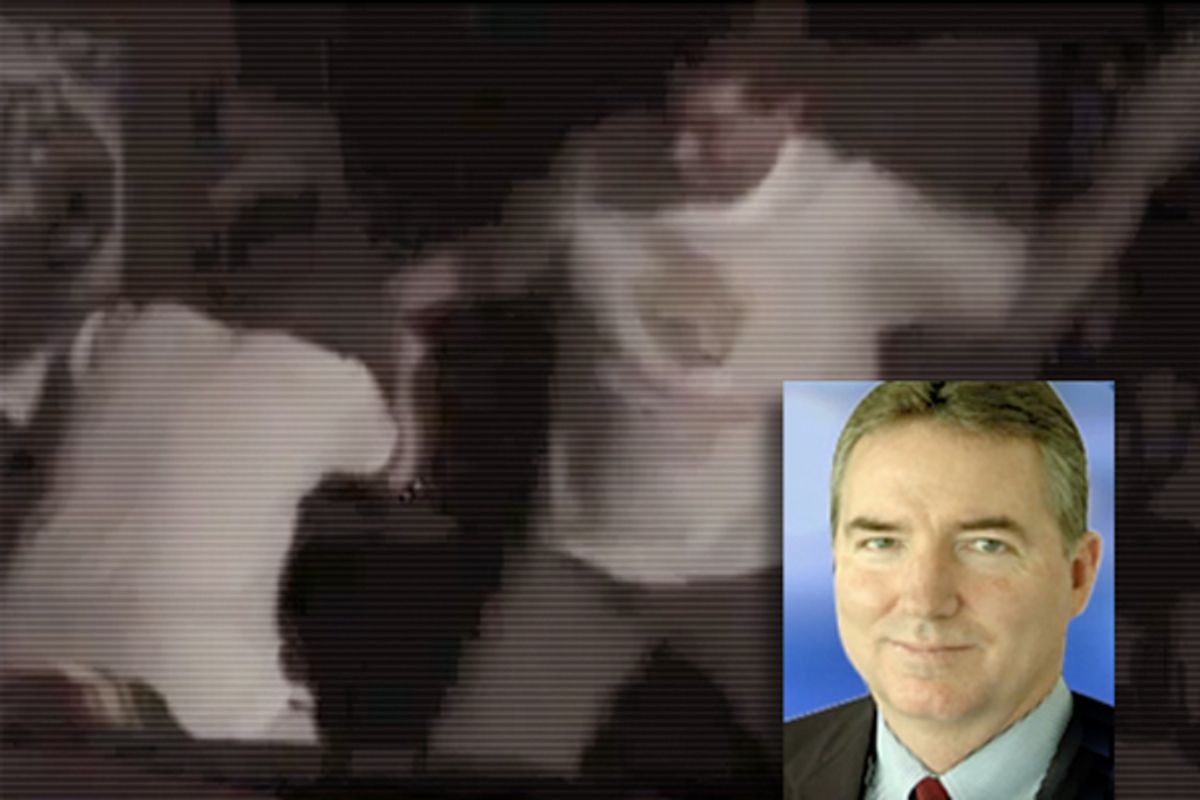

By now, the YouTube video of Texas county Judge William Adams and his wife, Hallie, savagely beating their disabled daughter, Hillary, then 16, has been viewed about two-and-a-half million times; this morning, it got the Matt Lauer treatment, with Hallie and Hillary at his side.

Whatever happens to the judge, whose duties include family court proceedings and juvenile offenses, his daughter told Matt Lauer he’d “been punished enough just by seeing this go public like this.” That shaming exposure wasn’t the only Internet-native method by which he’d gotten his comeuppance.

It’s what most abuse victims lack: incontrovertible proof. "People are believing us now, instead of calling us liars like they have in the past," Hallie, who has since claimed she was also abused by her husband, told a local TV station.

Indeed. Recorded in 2004 but put online less than a week ago, the video is seven-and-a-half minutes long, during which even people who might be disposed to corporal punishment might flinch. (That might include the Texas attorney general, whose website offers the following relativistic statement: “belts and hair brushes are accepted by many as legitimate disciplinary ‘tools’ and their use is not likely to be considered abusive, as long as injury does not occur.”) Other self-described victims of abuse envied this trump card; wrote one anonymous commenter, “I am thrilled she got it on tape and shared it with us. I wish I had the same, especially to show my parents now, as they deny it ever happened.”

But it wasn’t enough for there to be a video – it had to move through the Web. Views were catapulted by Reddit, which as Max Read noted, “has a strong protective streak.” And then it had to inspire the Internet-specific mode of action. Almost instantly, Facebook groups were launched to demand punishment. The statute of limitations on the criminal justice system may have passed, but Internet justice knows no expiration.

It’s a bizarre symmetry that the “reason” given for Hillary’s abuse that day was, according to her, downloading media illegally from the Internet. (The video is titled, “Judge William Adams beats daughter for using the internet.”) This is possibly what Judge Adams is referring to in his barely exasperated video interview with a local television station, when he says she was caught stealing. On "Today," Hillary said of her father that he “feared and didn’t understand the Internet.” And when she, years later, threatened to post the video online, he dared her to go ahead, showing that the latter was still true. Now his best excuse is, "It looks worse than it is."

Online masses don’t always mobilize for good; the sad tale of Jessi Slaughter is proof enough of that, as is the recent series of conversations about harassment leveled at bloggers who write about feminism and sexuality. But the incontrovertible victimization in the video, and its particularities – the judge’s hypocrisy, a note on the video that Hillary suffers from cerebral palsy, Hallie’s jarring statement that her daughter should take the beating “like a sixteen year old girl ... like a grown woman” -- brought out the rage against the victimizer. Technology shifted the power dynamics and mitigated the isolation of abuse, something advocates already hope can be a tool. Just this week, the White House announced the winners of its “apps against abuse” challenge, both of which involve using mobile phones to spread the word of sexual violence and assault to close friends and organizations.

Hillary says she released the video because her father had continued to abuse her. Her mother said on "Today" that she’d left her husband four years ago, that he was an addict and that she had been “brainwashed” by a cycle of abuse and dysfunction. (Her daughter says she forgives her.) But, she said, he was still abusing her through email and text messages.

The arc will end when official punishment gets levied on the judge, who has stopped talking. After all this, Hillary, whatever trauma she still experiences, is no longer an invisible victim of her father; she's a confident interlocutor who looked fully in control of the situation.

That reversal, and any consequences for the judge, can help us, the audience, believe that there is fairness and justice, that we can leave comments and sign petitions and join online groups to fix something -- at least with this one, highly visible case.

Shares