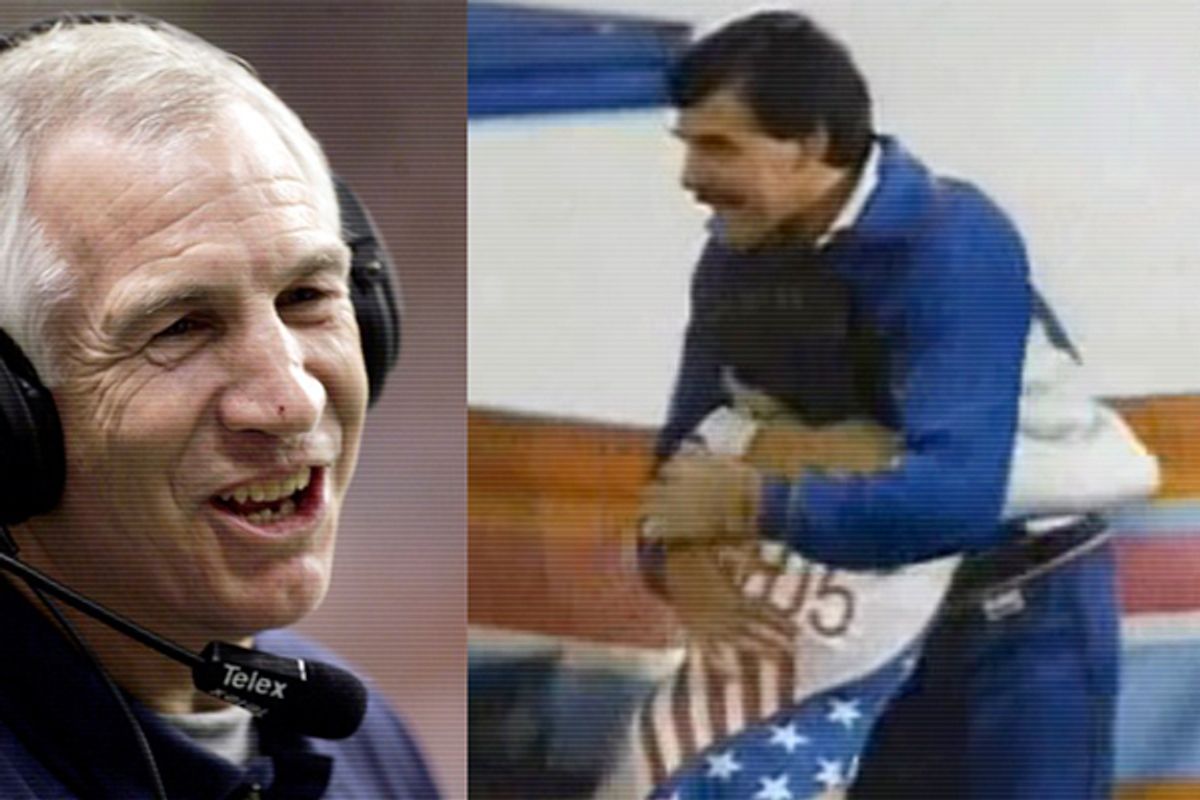

Disgust flows freely after reading each new story about Penn State. Why, we wonder, would someone willingly ignore reports of heinous sexual abuse of a child? Why would someone as “good” as Joe Paterno brush aside the alleged despicable and predatory actions of a coach on his staff, a coach representing his Nittany Lions? By all accounts, Paterno was the hero coach, a model of highly invested and supportive team building, a molder of men, a teacher and a mentor. As a thinking, feeling adult, it seems so obvious what the right choice would be. Report Jerry Sandusky to the police. No matter what.

So why are good people likely to do not so good things? Well, in the microcosmic world of hyper-competitive athletics, a high-performance culture where winning trumps all, obvious moral choices become blurred. The sport, the team, a berth on the squad, a medal on the stand – that becomes the priority. The parents, coaches and teams put everything else aside in honor of the win. I know this firsthand.

I was the 1986 national champion in gymnastics. I competed on broken bones, with black eyes, and went days without food. I broke my femur and had the cast removed more than a few weeks too early so that I could get back to training in time to compete at the U.S. Championships. I broke the opposing leg’s ankle in the process -- but I competed and won. Two bum legs, but I got the trophy. There was never any question about what I’d do. Long-term damage didn’t matter. My mental and emotional health didn’t matter. Winning did.

During this time, I met Don Peters, the coach of the U.S. national team and the head coach of a Southern California private club called SCATS. He was personally responsible for producing scores of national team members. And as the 1984 Olympic coach, he led that team to silver-medal glory and a record eight medals, including Mary Lou Retton's gold medal in the all-around.

Peters was revered. He was a legend in our sport, even if he was relatively unknown to the outside world. And within some corners of the team, he was rumored to be involved with one of the gymnasts at his club, Doe Yamashiro, one of my teammates on the national squad. I first wrote about it in my 2008 memoir "Chalked Up: Inside Elite Gymnastics' Merciless Coaching, Overzealous Parents, Eating Disorders and Elusive Olympic Dreams." Earlier this fall, Yamashiro said publicly that Peters began fondling her in 1986, when she was just 16, and began having sex with her when she was 17. This week, USA Gymnastics permanently banned Peters from coaching and kicked him out of the sport's hall of fame.

Some of us whispered about it at the Goodwill Games in 1986. Doe was with Peters all the time. She was shy and he kept her away from the rest of the team. She didn’t hang out with us in between practices, doing girly things like makeovers and diet soda binges. He squirreled her off to some private place. We wondered what happened when they were alone. I recall mentioning it offhandedly to my parents and other coaches at the event. Everyone waved it off. I almost giggled about it when I said it, so perhaps my revelation was not to be taken seriously. But it made me so uncomfortable, how else was I to share it?

As I wrote in the book, "It got to the point where we all joked about it. 'Where's Doe?' one girl would say, and we would all fall into a pile in fits of laughter. Nobody asked Don, 'What's going on here?' Everyone just let it happen."

Looking back, I was hoping someone, anyone, an adult with some common sense would have done something. But no one did. And the effect on me was: You girls don’t matter. He does. Because Don Peters creates winners, and that is the most important thing.

And so, despite the fact that I wasn’t sexually abused, the insidious effects of a culture that allowed it, are salient to me. You learn not to trust your own experience. Maybe I’m wrong? Maybe it’s fine. Everyone else seems to think it’s OK. If I am good, this won’t happen to me.

Morality viewed in the funhouse mirror of elite athletics is grotesquely distorted. And the distortion becomes invisible after a time. A parent or coach might say: What if the reports aren’t true? It would be unthinkable to ruin this great man’s reputation. Oh, and by the way, he might not let my daughter/gymnast compete in the next big meet if I implicate him in such ugliness. This all-powerful man will strike back and my daughter/athlete will suffer. We’ve worked too hard. Let’s let it slide.

So it slid for almost 25 years. Until this week, when Peters was issued that lifetime ban. More than 20 years later Doe Yamashiro found her courage, stopped believing that she was somehow complicit, or that maybe it wasn’t that big of a deal.

She told her story to the Orange County Register, and USA Gymnastics, the governing body for the sport, responded. They investigated and held hearings. Peters resigned his coaching positions, but the sport still expelled him for good. It took this long because those of us in the sport were enthralled by his power. And the same might have been true of Paterno. While he didn’t commit these alleged acts of abuse, he did run the legendary program. No one wanted to mess with that. Even now, students remain in his thrall, protesting his firing – because he made winners.

Pediatricians and other healthcare workers are required by law to report any suspected abuse of children. They can lose their licenses and their livelihoods if they fail to do so. Teachers are held to a similar standard. So why aren't coaches? They spend more time with the kids they coach than doctors or schoolteachers. I spent up to eight hours a day with my coaches. But coaches somehow exist outside the laws of child protection.

The solution needs to be legally mandated guidelines for coaches of minors. If the guidelines are violated, legal action must be taken. And the guidelines must specify that other member-coaches are required to report suspected abuse to child protective services. Adults cannot be compelled to “do the right thing” when there are wins at stake. They must be required to do so.

And child athletes must be encouraged to speak up when there is abusive or questionable behavior from a coach. All too often an athlete in this sort of relationship feels powerless. He questions his own rights, his own take on the experience. He is beguiled by the coach in hoping for that all too critical break -- the spot on the team or an extra hour of one-on-one training. So enthralled, the athlete is unable to come to his own defense -- and the lingering effects will last a lifetime.

Parents must demand regulation that has real legal implications -- not just a ban or a firing. The good coaches need to come to the defense of their beloved sports by requiring that the “bad coaches” be held to task in the eyes of the law. And we all must insist that coaches are teachers of children first, and champion builders a far, far distant second.

Shares