The book business may be undergoing tectonic changes brought on by the booming popularity of e-books, the consolidating power of Amazon.com and the wobbly state of bricks-and-mortar bookstores, but books themselves are better than ever.

The 10 best books of 2011 (five fiction, five nonfiction) feature characters ranging from empresses to impostors, settings as far flung as Amazonian jungles and secret Antarctic cities, themes as compelling as love, race, class, art, revolution and the very nature of communication itself. (We revealed the top fiction titles yesterday.) At at time when the economic horizon often seems to be contracting, the curiosity and imagination of authors know no bounds. It's amazing how far you can travel and how much you can discover, all for the modest price of a book.

2011's BEST NONFICTION

"Townie" by Andre Dubus III

When Dubus' parents (his father was the revered short-story writer Andre Dubus Jr.) split up, he, his mother and his two siblings were relegated to a financially precarious existence in a New England mill town. He found their working-class neighborhood to be a realm of peril, where drugs, petty crime and, above all, pointless violence lurked around every corner. Survival meant cultivating a hard, aggressively macho carapace, but Dubus' occasional visits with his father showed him that there was a world of thought, tranquility and art out there somewhere, however inaccessible it seemed. The inspiration offered by these encounters was equaled only by the pain of his exile. "Townie" is the story of how Dubus made the journey to his own writer's life, and also of how he almost didn't make it. Unsparing and occasionally brutal, but never bitter, it's an exceptionally eloquent depiction of something many Americans have experienced in the past three years: what it feels like to be left behind.

READ SALON'S REVIEW

"Love and Capital: Karl and Jenny Marx and the Birth of a Revolution" by Mary Gabriel

Of all the gallons of ink that have been spilled in discussion of Karl Marx, relatively few drops have been devoted to his family life. Gabriel corrects that deficiency, portraying the budding revolutionary's relationship to his worried father, a Jewish lawyer, and his eventual marriage to Jenny von Westphalen, the beautiful daughter of a Prussian baron. She follows the young couple as, inflamed by the appalling miseries suffered by the underclass created by industrialization, they surrounded themselves with like-minded malcontents and tried to hammer out a vision of a better society. They were rich in ideas and friends -- including Marx's collaborator, the suave Friedrich Engels, as well as nearly every other radical of the time -- but muddled along in material poverty. Three of their six children died before reaching adulthood, and while Marx treated Jenny as his intellectual equal, he also subjected her to the unhappiness of knowing that he fathered an illegitimate child by their housekeeper. Learned and wide-ranging but unfailingly lively, "Love and Capital" illustrates how that long-lost generation applied themselves, emotionally as well as intellectually, to fighting the inequities of their day.

READ THE B&N REVIEW'S REVIEW

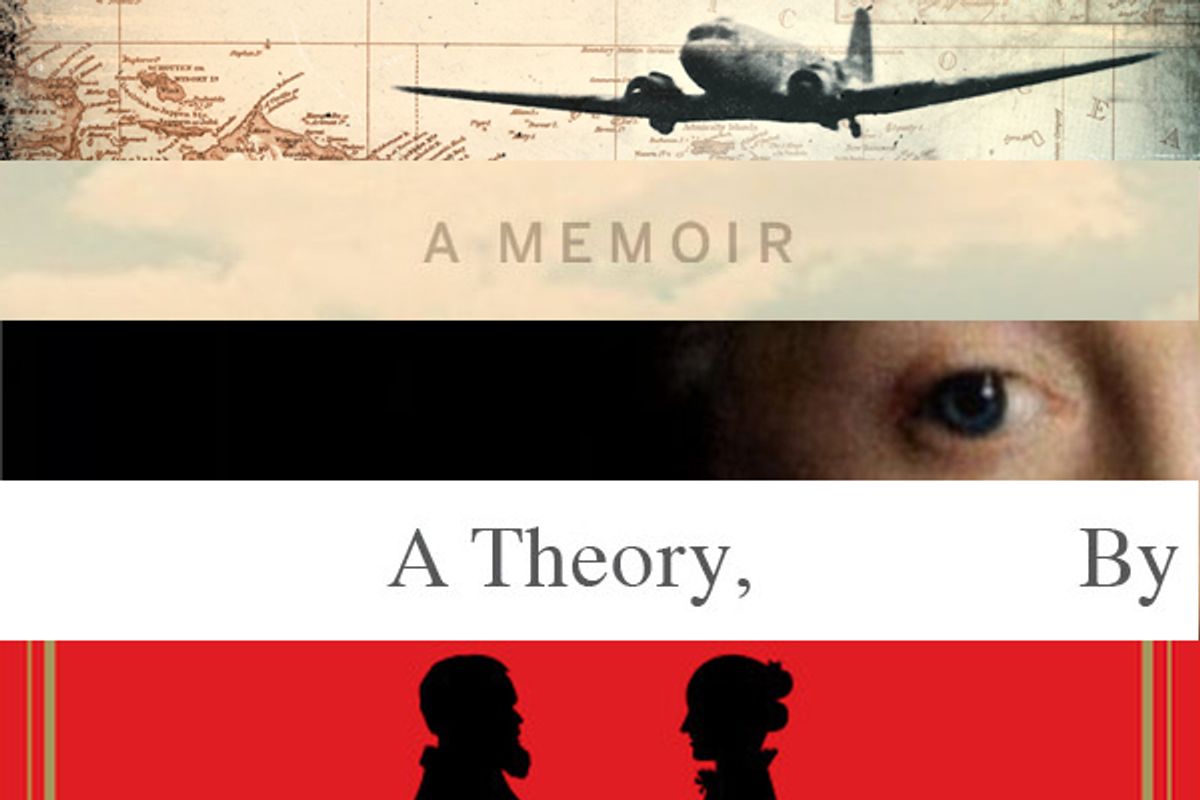

"The Information: A History, a Theory, a Flood" by James Gleick

If the statement "The universe is made of information" seems inscrutable but intriguing to you, then dig in to Gleick's grand, lucid and awe-inspiring history of how a Bell Labs researcher working on telephony and cryptography in the mid-20th century help lead humanity to just that revelation. The researcher was Claude Shannon, but he's only the central figure in this sweeping history of information theory, a history that takes up such thinkers as Charles Babbage and Ada Lovelace, Kurt Godel, Francis Crick, Samuel Morse, Richard Feynman and Jorge Luis Borges. Along the way, Gleick considers communication vessels ranging from African tribal drumming to Wikipedia, but information is about a lot more than what human beings have to say to each other. It's the very stuff of reality, and never have its mysteries been offered up with more elegance or aplomb.

"Catherine the Great: The Portrait of a Woman" by Robert K. Massie

She began as obscure 18th-century German princess and she ended up an empress, the embodiment of her era's ideal of the enlightened despot and one of Russia's longest-reigning and most effective rulers. To get there, Catherine the Great had to overcome a feckless, self-centered mother; a capricious imperial sponsor; a petulant ninny of a husband; an endlessly intriguing court and a coup. Massie (author of the bestselling "Nicholas and Alexandria") is rather imperial himself, taking command of a daunting amount of material to deliver a narrative both delicious and edifying, equal parts serious history and aristocratic soap opera. It helps that his main character is so intelligent, frank, passionate and merry, capable of impressing the likes of Voltaire with her learned correspondence in the morning and swooning over a handsome count by candlelight. A great life, indeed, and irresistibly told.

READ THE B&N REVIEW'S REVIEW

"Lost in Shangri-La" by Mitchell Zuckoff

When an Army transport plane crashed in a remote, mountainous region of Dutch New Guinea in the waning days of World War II, only three of the two dozen passengers survived: a sergeant who sustained a serious head wound, a lieutenant who lost his twin brother in the crash and an improbably beautiful WAC corporal. They'd come down in a valley populated by Stone Age tribesmen who practiced ritual cannibalism and regarded their visitors as eccentric spirits heralding the dawn of a new way of life. The surrounding mountains made rescuing the survivors a logistical nightmare, so a crack team of Filipino-American paratroopers was dropped in to help out. (Eventually, the Army settled on a hair-raisingly risky glider operation to extract them.) Zuckoff's muscular yet sensitive account of the crash and rescue is exciting but never sensational, and richly researched -- he even interviews some of the surviving tribespeople to learn their side of the story. (One's still mad about the air drop that killed her pig.) This is the sort of outrageous-but-true adventure story that seems to tell itself -- until you've seen a few writers blow it. Zuckoff gets it just right.

Shares