The fall of the Roman Empire is traditionally dated to 476 CE, the year when the last emperor, Romulus Augustulus, was deposed. There is a pleasing symmetry in the fact that the last emperor's name should pay homage to the founder of Rome and the founder of the Empire; but to those who lived through it, the fall of Romulus Augustulus would not have felt like much of a milestone. By then, the transformation of the Roman Empire had been going on for at least a century, as a series of radical changes put an end to its age-old identity: the official conversion to Christianity under Constantine, the splitting of the empire into Western and Eastern halves, and the unstoppable invasions of Germanic tribes, many of which carved out new kingdoms on imperial territory. This period of transition, beginning in the fourth century CE, can be seen as "late antiquity" or the early Middle Ages, and it has been the focus of some of the most exciting classical scholarship in recent years.

It's fitting to close out my three-part appreciation of the Loeb Classical Library (here are parts one and two), then, by looking at two works from the sixth century CE, near the chronological end of the series. The lives of Boethius, author of "The Consolation of Philosophy," and Procopius, author of "The Secret History," overlapped, and between them they neatly embody the two halves of the imperial legacy. Procopius was born about 500 CE in Caesarea, in the Roman province of Palestine. He spent his life in the service of the Eastern Roman Empire, which continued intact after the Western Empire had disintegrated into a group of barbarian kingdoms. Anicius Manlius Boethius, born about 480 CE, was a servant of one of those kings: Theodoric, the Ostrogothic ruler who established control over much of Italy. Procopius wrote in Greek, Boethius, in Latin; the former was a historian, the latter a philosopher and theologian. Read together, their most famous works offer a powerful portrait of an age of violent transition, which even at the time looked like a decline and fall.

It's fitting to close out my three-part appreciation of the Loeb Classical Library (here are parts one and two), then, by looking at two works from the sixth century CE, near the chronological end of the series. The lives of Boethius, author of "The Consolation of Philosophy," and Procopius, author of "The Secret History," overlapped, and between them they neatly embody the two halves of the imperial legacy. Procopius was born about 500 CE in Caesarea, in the Roman province of Palestine. He spent his life in the service of the Eastern Roman Empire, which continued intact after the Western Empire had disintegrated into a group of barbarian kingdoms. Anicius Manlius Boethius, born about 480 CE, was a servant of one of those kings: Theodoric, the Ostrogothic ruler who established control over much of Italy. Procopius wrote in Greek, Boethius, in Latin; the former was a historian, the latter a philosopher and theologian. Read together, their most famous works offer a powerful portrait of an age of violent transition, which even at the time looked like a decline and fall.

It's doubly ironic that Procopius should be best known today for his "Anecdota," a title that literally means "Unpublished Notes" and is usually translated as "The Secret History". First, because this work was so scandalous and at times pornographic that it remained practically unknown for centuries after it was written in the 550s -- the first Latin translation was not made until the seventeenth century. And second, because "The Secret History" constitutes a repudiation of the much longer historical works that made Procopius famous -- the "Wars of Justinian" and the "Buildings of Justinian".

Those books are our main source for one of the most important periods in Byzantine history, the reign of the Emperor Justinian from 527 to 565. Justinian is remembered for three hugely ambitious undertakings: building the Hagia Sophia cathedral in Constantinople; codifying the whole body of Roman law in the" Corpus Juris Civilis," thus transmitting its legacy to the Middle Ages and beyond; and attempting a reconquest of the Western Roman Empire, under his great general Belisarius. All this sounds like enough to ensure his reputation, which Procopius' own works did much to promote.

But "The Secret History" begins by confessing that those works were not the whole story. "It was not possible, as long as the actors were still alive, for these things to be recorded in the way they should have been," Procopius writes. "Nay, more, in the case of many of the events described in the previous narrative I was compelled to conceal the causes which led up to them." Only now will he reveal the whole truth -- even though, he acknowledges, the stories he is about to tell are so grotesquely outrageous that "such things...will seem neither credible nor probable to men of a later generation." (He was right about that. The editor of the Loeb edition, H. B. Dewing, says in the introduction that Procopius' "testimony...falls to the ground through the weight of its own extravagance.")

The central message of "The Secret History" is that Justinian and his wife, the Empress Theodora, were evil incarnate, the most depraved and cruel human beings who ever lived. That is, if they were even human:

And some of those who were present with the Emperor, at very late hours of the night presumably, and held conference with him...seemed to see a sort of phantom spirit unfamiliar to them in place of him...the head of Justinian would disappear suddenly, but the rest of his body seemed to keep making these same long circuits.... And another person said that he stood beside him when he sat and suddenly saw that his face had become like featureless flesh; for neither eyebrows nor eyes were in their proper place."

If Justinian was a bodiless demon, Theodora was all too fleshly for Procopius's liking. His sketch of her is a masterpiece of character assassination that even the National Enquirer would consider outré. Evidently, Theodora started life as a child prostitute and became a notorious sex maniac: "[S]he used to take Nature to task, complaining that it had not pierced her breasts with larger holes so that it might be possible for her to contrive another method of copulation there." One of her specialties, Procopius writes, was a sex show in which geese would peck grains from her genitals -- a pornographic version of Leda and the Swan.

Underneath all the lurid details and denunciatory rhetoric, however, it is possible to see Procopius as responding to real historical developments – though we might well draw different conclusions than he did. When he blames Justinian for handing over the wealth of the Empire to barbarian tribes, he is lamenting a shift in the balance of power that no single emperor could have caused or cured. And where he is suspicious of Justinian for staying up late at night or for changing so many traditional laws, we might glimpse an admirable ruler, one working hard to adapt his government to a changing world.

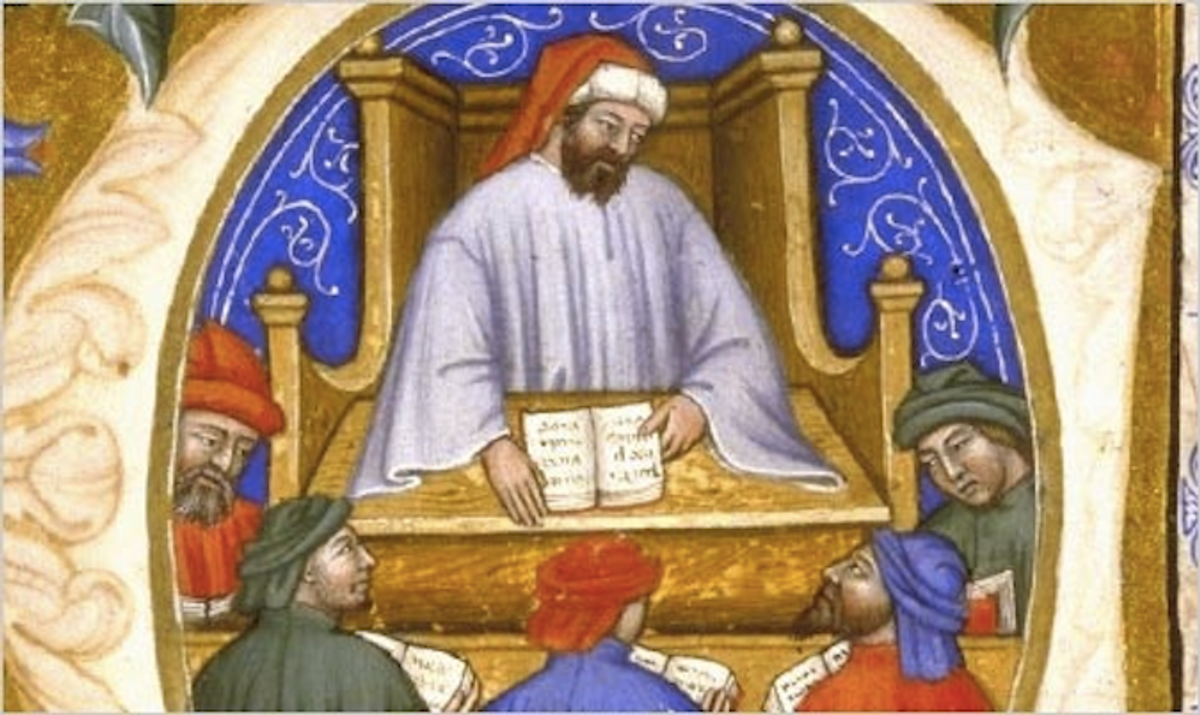

If Procopius responds to change with anger and recrimination, Boethius' response was altogether more sublime. After a career in which he served Theodoric in high office and amassed great wealth, he was accused of plotting against the king in order to restore the old Roman Senate -- charges that led to his execution in 524 CE. In the period between condemnation and death, while he was evidently under house arrest, Boethius composed "The Consolation of Philosophy," setting down in alternating passages of verse and prose everything he had learned about stoicism in the face of adversity.

As the book opens, Boethius is lamenting his fallen condition in a poem: "Ah why, my friends, / Why did you boast so often of my happiness? / How faltering even then the step / Of one now fallen." He is interrupted by the sudden appearance of Philosophy in the form of a woman: "Her look filled me with awe; her burning eyes penetrated more deeply than those of ordinary men; her complexion was fresh with an ever-lively bloom, yet she seemed so ancient that none would think her of our time." Sternly, Philosophy shakes Boethius out of his self-pity and proceeds to explain, in the form of a Platonic or Ciceronian dialogue, all the reasons why men should not be downcast by bad fortune.

Remarkably, although Boethius was a Christian -- indeed, the "Consolation" appears in a Loeb volume along with several of his theological tracts -- he never employs Christian arguments or even mentions Jesus as a source of support. Instead, he allows Philosophy to set forth a classic stoic argument. Fortune is inherently fickle, always spinning her wheel; we should actually be grateful for bad luck, because it reveals the truth about the instability of fortune. The only true source of happiness lies within ourselves -- not in riches, power, or fame, whose claims Philosophy considers and dismisses.

The book culminates in a vision of a divinely ordered cosmos in which everything is ordained for the best, no matter how unjust it may look from the human perspective: "There remains also as an observer from on high foreknowing all things, God, and the always present eternity of his sight runs along with the future quality of our actions, dispensing rewards for the good and punishments for the wicked." In a time like Boethius', when all the old verities were falling apart, this kind of certainty was desperately needed. But like all the best of classical literature, it is no less resonant today. As long as injustice and misfortune touch our lives, we can be grateful for the consolation of Boethius' "Consolation."

Shares