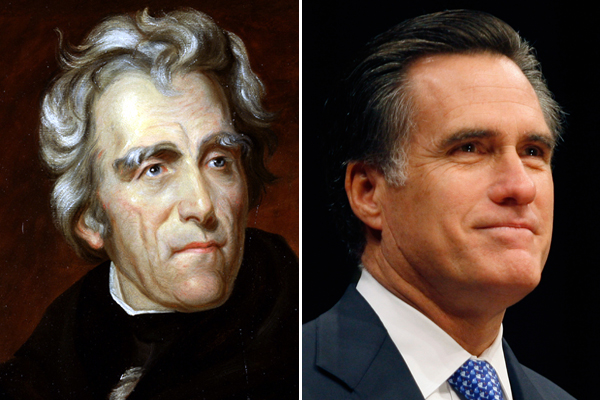

If Mitt Romney receives the Republican presidential nomination, he will be the third upper-class candidate in a row nominated for the presidency by a party that speaks in the accents of Jacksonian populism and pretends to be against “elites.”

America may not have titled aristocrats, but it has always had patrician families, defined by a combination of wealth, educational affiliations and public service. Today’s Republicans may sound like George Wallace in their denunciations of paper-pushing bureaucrats and pointy-headed intellectuals, but their presidential selection pool is a very selective country club.

Between 1980 and 2008, inclusive, there have been eight presidential elections. The Republicans have nominated five presidential candidates — Ronald Reagan, George Herbert Walker Bush, Bob Dole, George W. Bush and John McCain. During the same time, the Democrats have nominated seven presidential candidates — Jimmy Carter, Walter Mondale, Michael Dukakis, Bill Clinton, Al Gore, John Kerry and Barack Obama.

The middle-class Republican candidates — Reagan and Dole — have been outnumbered by the candidates born into the social elite — the two Bushes and McCain. George Herbert Walker Bush’s father, and George W.’s grandfather, Prescott Bush, was a wealthy Connecticut senator, whose own father, Samuel Prescott Bush, was a rich steel and railroad company executive. John McCain’s father and grandfather were both four-star admirals.

Among Democratic presidential nominees in the same era, only Kerry — related to the wealthy Forbes, Winthrop and Dudley families of the Northeast — could claim anything like the pedigree of the Bushes. If it takes three generations to make a gentleman, or even two, Al Gore doesn’t qualify as upper class. His father, who preceded him as a senator from Tennessee, came from a modest background and received his law degree from the Nashville YMCA Night School of Law. The other Democratic nominees in the 1980-2008 period came from middle-class backgrounds, like Barack Obama, the son of two college professors. Bill Clinton was born into the lower middle class.

The plot thickens further, when Republican denunciations of government as tyranny are contrasted with the multi-generational commitment to public service on the part of Republican presidential candidates. Samuel Prescott Bush, who served in the government during World War I, founded a dynasty that has produced a Connecticut senator, Prescott Bush; a Texas congressman and president, George Herbert Walker Bush; a Texas governor and president, George W. Bush; and a Florida governor, Jeb Bush. John McCain, as we have seen, is the heir to a family tradition of military service. Mitt Romney, the former governor of Massachusetts, is the son of George Romney, who was governor of Michigan.

So much for pork-rind populism.

The mystery deepens even further. In the 19th century, the Republican Party was founded by Abraham Lincoln and others, devoted to the Henry Clay’s idea of the “self-made man.” But in spite of conservative rhetoric about small business, today’s Republican economic orthodoxy does not promote the interests of entrepreneurs or industrial capitalism. Instead, it promotes the economic interests of rentiers — families with inherited wealth and Wall Street investors — the kind of people who make money in their sleep, in the words of the 19th-century classical liberal economist J.S. Mill, who despised them.

The GOP crusade to abolish the estate tax — the “death tax” — does nothing for American business in general, even as it chiefly benefits the trust fund babies of a few super-rich families. A lower tax rate for capital gains than for earned income means that the idle rich, and the hedge fund managers who manage their assets and are taxed at the capital gains rate, pay a much lower tax rate on their income than the majority of Americans who depend on wages or professional fees for a living. Self-made entrepreneurs? Hardly.

Nor does Republicanomics serve the interests of captains of industry. If the Republican economic plan were drafted by CEOs of American-based companies that actually make things, rather than rearrange money, it would not necessarily please liberals but it would bear little resemblance to the rentier-friendly plans pushed by the Wall Street right. The emphasis would be on a permanent R&D tax credit, lower corporate taxes, depreciation allowances, public infrastructure investment, policies to lower the costs of energy and other inputs, dollar devaluation and other policies to promote the inshoring of production in America. Genuine captains of industry would not assign priority to estate tax relief and low capital gains taxes for the benefit of the trust fund set like the Bushes and Romneys.

The conclusion is inescapable. The Republican Party is not really a pro-business party at all. It is a pro-hereditary wealth party. Its platform serves the interests of those few Americans who are born into wealth and seek to preserve their fortunes, not those who start new companies or invent new technologies. Naturally, therefore, the party’s presidential candidates are chosen nowadays from among the pedigreed, hereditary social elite who are the chief beneficiaries of its policies.

How is it, then, that the party of old money has succeeded in winning the vote of the white working class since Nixon and Reagan? To understand how this could occur, we need only look at American history.

In the 19th century the Jacksonian coalition, then identified with the Democrats beginning with Andrew Jackson, was, like the Republican Party today, based on an alliance of white Southerners and Southwesterners with working-class whites in the North. Like today’s neo-Jacksonian Republicans, the original Jacksonians posed as the champions of the common man, denouncing government tyranny and privilege.

But Jacksonian common-man rhetoric was a camouflage for the interests of the most parasitic rentier elite in American history: the Southern slaveowners, including Andrew Jackson himself. The rentiers of the plantation South were allied with Northern crony capitalists — businessmen and bankers who sought to loot the public domain by means of what today would be called “privatization.” That is why the Jackson administration destroyed the Bank of the United States, a quasi-public agency that was the largest corporation in the country, and distributed its financial assets to “pet banks” allied with Jackson and his cronies. The modern equivalent would be the privatization of Social Security and Medicare and the diversion of their vast revenues into private hands, which, of course, is the centerpiece of the Republican economic agenda for America.

Old or new, Jacksonianism has always combined the pretense of egalitarian rebellion against privilege with the reality of domination by upper-class rentiers and crony capitalists. In the 21st century as in the 19th, the Jacksonian oligarchs divert the attention of their yeoman followers from what is going on by means of military jingoism (Jackson bellowed at France, today’s Republicans threaten Iran). Central to the Jacksonian tradition is the exploitation of paranoid fears of federal tyranny, combined with dark undercurrents of racism (witness Ron Paul’s recent denunciation of the Civil Rights Act and the blacks-on-welfare trope cynically deployed by Gingrich and Santorum).

Can the Jacksonian trick of enlisting the white working class in the service of hereditary wealth and crony capitalism work again? Why not? It has worked before.