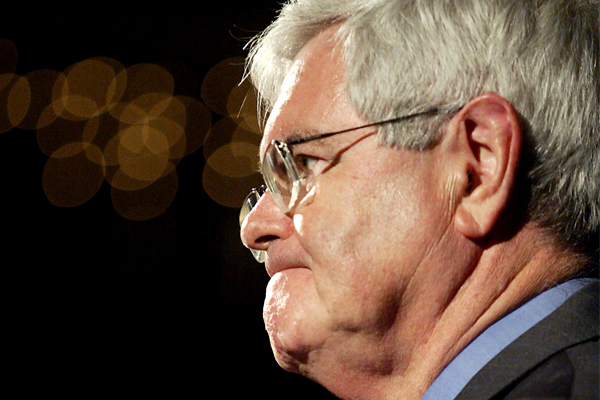

Newt Gingrich is a boastful kind of guy. But when it comes to Wall Street, the former House speaker is surprisingly modest. He has taken a moderate tack, not talking much about it (except to say that he was not a lobbyist for Freddie Mac, God forbid). He’s even said that banks are too quick to foreclose and that deregulation of Wall Street in the 1990s was “probably a mistake.”

Judging from those remarks and the brickbats he has thrown at Mitt Romney, ripping into his record as a former slash-and-burning private equity guy, you’d think that Gingrich doesn’t much like Wall Street. Au contraire. A testimony before Congress in 2006, when he was still in the “consulting” business, shows that Newt Gingrich is a passionate defender and advocate of the interests of the securities industry, and passionate about making life hard for consumers, investors and anyone who has a beef against Corporate America.

Since he doesn’t have to disclose such things, it’s not known which client or clients paid Gingrich to appear before the capital markets subcommittee of the House Financial Services Committee on April 26, 2006. He didn’t appear to be directly pushing the interests of Freddie Mac, the client that has gotten the most attention. (Of course, it’s possible that the former House speaker was just a citizen speaking his mind, and if you believe that, there’s a bridge over the East River I want to sell you.) What we do know is that he was unabashed in his advocacy of the Street, tailored to the concerns of the bankers in those carefree pre-crash days.

It’s surprising that Gingrich’s Republican opponents, who also carry water for the Street but are not above hypocrisy, haven’t mentioned his testimony so far. It can be found in the pdf link in this congressional Web page, which is the transcript of a thoroughly routine hearing titled “America’s Capital Markets: Maintaining Our Lead in the 21st Century.” Gingrich’s testimony begins on Page 14, and his prepared statement, bearing the imprint of Gingrich Communications, is in the appendix on Page 102.

This wasn’t Gingrich as a lofty “historian” but Gingrich the policy wonk, deep in the weeds, pushing the Wall Street agenda. He quotes the American Enterprise Institute copiously and repeats right-wing talking points on tort reform.

Gingrich began by recommending the gutting of Sarbanes-Oxley — the legislation, passed after the Enron scandal in 2002, that was a weak attempt to deal with corporate chicanery — on the grounds that complying with its simple provisions was “too expensive.” Sarb-Ox discomfited public companies by requiring them to swear to the accuracy of their financial reports, and also set up safeguards against accounting chicanery by creating a Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (PCAO).

Gingrich contended that “fundamental overhaul of Sarbanes-Oxley” would prevent stock listings from fleeing overseas, similar to the argument often made by the right — and equally bogus — that raising taxes will send corporations fleeing across the Atlantic. He wanted Section 404 of Sarbanes-Oxley, which requires companies to report on the state of their internal controls, to be made voluntary and not mandatory.

“This approach,” he said, “would be well suited to a market economy and a free society.” And, he might have added, it would be well-suited to companies like Enron and WorldCom, which cheated their investors by deciding not to have particularly good internal controls.

Gingrich also wanted Congress to take a stand for haziness in accounting, something that would be like manna from heaven for companies desiring to fudge their numbers. He told the committee that it was necessary to “state clearly that Congress does not have the naive belief that accounting is something objective, but rather understands, as every financial professional does, that accounting is full of more or less subjective judgments, estimates of the unknowable future, and debatable competing theories. As the saying goes, it is art, and by no means science.” This sounds less like a line from congressional testimony than something Max Bialystock might have said in “The Producers.”

And just to be sure that little old ladies could continue to be ripped off by the crooked-CPA Leopold Blooms who work for the Max Bialystocks producing corporate “Springtime for Hitler,” Gingrich would have hobbled the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board, which is supposed to keep a watchful eye over the auditing firms that certify to the correctness of corporate disclosures. Gingrich’s proposal would have turned it into a political football under the aegis of the notoriously corporate-influenced Congress. He wanted the PCAOB “subject to appropriations, oversight and a normal appointments process.”

That all sounds technical, but it’s not. Gingrich would have rolled back the only, slim protections that the public received from crooked companies after the scandals of a decade ago. And he was just getting warmed up.

At the time, state attorneys general, led by the morally dodgy but aggressive New York Attorney General Eliot Spitzer, had been ripping into Wall Street analysts who put out misleading reports that were often tinged by conflicts of interest. That made Spitzer the most hated man on Wall Street. Gingrich would have none of that. He would not only “rein in state Attorneys-General” who were annoying Wall Street, but would see to it that states are not allowed to have securities law that might be tougher than federal regulations at protecting investors.

“We must have a uniform national set of securities regulations,” Gingrich told Congress, pushing a longtime securities industry priority. “To the extent that state Attorneys-General are encroaching in this rule-making area, then the Congress should direct the [Securities and Exchange Commission] to preempt such state action.” Translation: Goodbye states’ rights, if they discomfit bankers. He calso astigated the state attorneys general who “have reaped publicity and political advantages through their pursuit of multi-state litigation targeting the tobacco, pharmaceutical, software and financial services industries. A few Attorneys-General have gained national attention by speaking to the media during the pendency of investigations.”

In Gingrich’s administration, you could forget about states taking action against corporate malfeasance, such as the coordinated action against Big Tobacco in the 1990s. At the time Gingrich lamented the tobacco settlement, in which the cigarette makers were forced to yield to a coordinated assault by state A.G.s. “This blackmail model of Attorneys-General championed by New York’s Eliot Spitzer, which mugs companies without going to court, is a job killer,” he said. “These practices must be stopped.”

Gingrich moved on to another longtime item on Wall Street’s wish list, “litigation reform,” aka “tort-reform.” Simply put, it is aimed at making it harder — if not impossible — for private citizens to face off in court against big corporations, as either plaintiffs or defendants. In his 2006 testimony, he spoke up for a particularly pernicious trend: the privatization of justice. Over the years, the ability of consumers to take businesses to court has been eroded, with a variety of companies — banks, credit card companies, cellphone outfits, brokerages and even some Internet retailers — requiring customers to take any disputes to arbitration, where they often are put at a disadvantage. Efforts in Congress to address this pernicious issue have stalled.

Under the subhead “Arbitration Preferable to Litigation,” Gingrich hewed closely to the corporate line on this hot-button consumer issue. Then he took the privatization principle one step further. Gingrich said, “Everyone should know that rapid, inexpensive arbitration is preferable to litigation. Cases involving technical knowledge should go first to panels of experts (health courts in the case of medical malpractice), but plaintiffs should be able to appeal to a court if they feel cheated. They should, however, have to carry the result of the expert panel with them into the litigation.”

If enacted, such a sweeping change in the court system would effectively screw every person who has ever been a victim of bad professional services, be it medical malpractice or crooked stock market brokers, because a “panel of experts” — and not an impartial jury — would determine the outcome. The ability to appeal such panels would be meaningless, if they have to “carry the result” into court. “Expert panels” are already forced on brokerage customers, who are required to forgo their right to a court trial, and bring cases to securities industry panels instead. The brokerage arbitration system has been widely criticized as a network of kangaroo courts.

Gingrich would further tilt the playing field against ordinary citizens by creating a “losers pay” system, with possible treble damages imposed on plaintiffs found to bring cases “without substance.” Obviously, such a system would make lawyers more reluctant to take potentially difficult cases, as the tobacco litigation was in the 1980s when most courts ruled against people suing tobacco companies.

As if that’s not enough to cripple the ability of people to sue corporations, Gingrich would dismantle the entire system of class action litigation, making it impossible for law firms to organize lawsuits against companies. In many cases, such as asbestos litigation, attorneys have proactively sought out clients. No longer. Instead “the injured parties should originate the lawsuits and hire the law firm,” Gingrich said. “The judge should have the option of opening the class action lawsuit to competitive bidding to find the least expensive law firm for the injured parties.”

Some of that sounds like a litigant-protection scheme, but it’s not. Had that system been in effect, the aggressive and organized private lawyering that led to the capitulation of Big Tobacco — and which has been used in every major class action, including those involving securities firms — would have been impossible. Sure, class-action lawyers are sometimes sharks, sometimes dishonest or even criminal, but Gingrich would attack those sharks by, in effect, poisoning the ocean.

Note that Gingrich, on behalf of his unidentified client or clients, went well beyond protecting Wall Street. His was a wide-ranging attack on the interests of consumers and investors — the people whose votes he is seeking in Florida. Naturally, he doesn’t care to talk about it on the campaign trail, except to insist, against the evidence, that he did not act as a lobbyist but as “a citizen.”

“As a citizen, I’m allowed to have an opinion,” as he told the New York Times last month.

The identity of whoever paid him to appear before Congress in April 2006 is really beside the point. Gingrich was expressing heartfelt views. If he becomes president and delivers on his pro-Wall Street crusade, he will make Ronald Reagan seem like Ralph Nader.