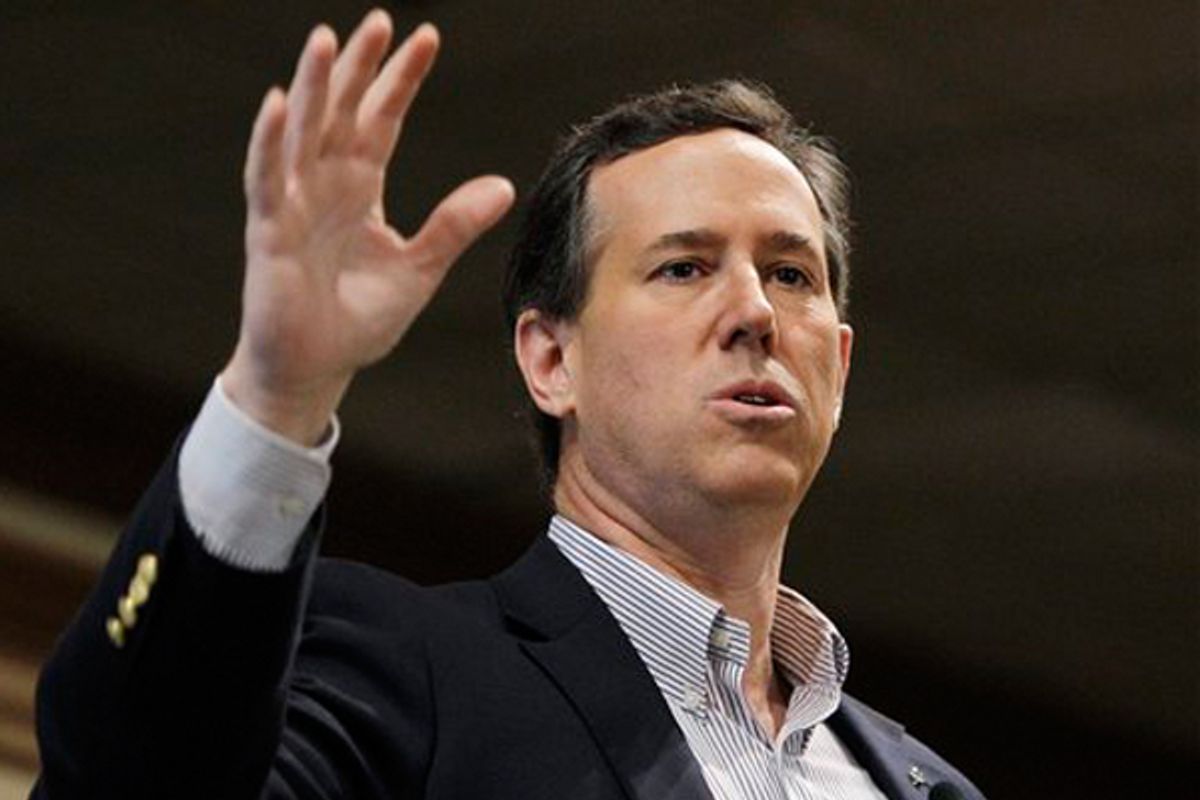

Rick Santorum’s decision to actively seek Democratic support in Michigan, where crossover voting is allowed in primaries, makes plenty of strategic sense. But it also comes with a risk – something that John McCain discovered 12 years ago.

As first reported by TPM last night, the Santorum campaign has been reaching out to Democratic voters with a robocall that conveys this message:

“Michigan Democrats can vote in the Republican primary on Tuesday. Why is it so important? Romney supported the bailout for his Wall Street billionaire buddies, but opposed the auto bailout. That was a slap in the face to every Michigan worker. And we’re not going to let Romney get away with it.”

There’s obvious political wisdom to this. Polls heading into today are basically even, but Romney appears to have a significant built-in advantage thanks to early voting. So if Santorum can expand the voting universe at the last minute and win a disproportionate share of the new participants, it could neutralize Romney’s banked votes.

And the message Santorum is using to court crossover support – Romney opposed the auto bailout! – probably has real resonance with Michigan Democrats, particularly union members, and is reinforced by Romney’s well-documented struggles to transcend his top 1 percent image. The irony, of course, is that Santorum opposed the auto bailout too and is pitching an economic agenda that may be even more hostile to blue collar and middle class voters than Romney’s, although Santorum’s personal roots and public style are more middle class than Romney’s.

The risk for Santorum is that if his ploy succeeds, it will give Romney an opportunity to argue that the Michigan result should come with an asterisk. This is how George W. Bush avoided serious damage 12 years ago, when John McCain upset him in the state by eight points, 51 to 43 percent.

Of course, the circumstances of that race were much different. The 2000 Michigan primary came just days after Bush posted a solid victory in South Carolina, a result that had seemingly restored order to the race after McCain’s stunning 19-point upset in New Hampshire. The expectation was that Bush, who enjoyed the almost unanimous backing of Republican establishment figures, would win decisively in Michigan and effectively end the race. Even McCain’s camp acknowledged that their candidate couldn’t survive a loss.

But by that point, McCain had also emerged as a national political rock star, celebrated by the press and Democrats for his “straight talk,” reformer’s pose, and willingness to stand up to the Big Bad Bush Machine. Polls showed McCain faring far better than Bush in general election trial heats with Al Gore. The GOP primary process was making McCain a hero to Democrats.

Needing a Michigan miracle, his campaign sought to leverage this popularity for votes, seeking crossover support just as Santorum is doing now. It helped McCain that the Democratic primary between Gore and Bill Bradley was canceled when both candidates removed their names from the ballot in solidarity with a DNC rule discouraging states from holding open primaries. Thus, Democratic and independent participation in the Bush/McCain primary surged, and the results were stark. Among Republicans, Bush pulled an estimated 68 percent of the vote; but among independents McCain did just as well, and among Democrats he positively slaughtered Bush.

The immediate effect was the hand McCain a crucial victory that kept his campaign alive. But the nature of his victory permitted Bush to boast at his first post-Michigan event that “you’re looking at a man who got 68 percent of the vote in Michigan.”

"I want to congratulate my opponent for a race well run,” Bush said. “But he's going to learn that in the long run it's going to be Republicans and like-minded independents who make the decision in this primary."

He was right about that. By relying so blatantly on Democratic votes, McCain further alienated a Republican establishment that already deeply distrusted him, and in the days that followed they attacked him with new intensity and resolve. A new talking point was born: “Mischievous” Democrats were trying to boost McCain because they saw him as a weak general election candidate. Never mind that this wasn’t the case at all; the pro-Bush crowd repeated it over and over. Support for Bush became a litmus test of Republican Party loyalty, which gave McCain no chance outside of the Northeast on Super Tuesday in early March. After Bush gobbled up the lion’s share of delegates that day, McCain exited the race.

Not surprisingly, Romney is now trying to frame Santorum’s robocalls as an act of partisan disloyalty, calling them “a new low for this campaign.” If Santorum wins by a tiny margin tonight, you can expect the Romney campaign to scream that mischievous Democrats put him over the top. And if Romney wins by a small margin, surely his campaign will claim that the result would have been much more substantial, if not for Santorum’s alliance with the left.

The good news for Santorum is that the dynamics of this race are far different than in 2000. The entire premise of his candidacy is that he’s more reliably conservative than Romney. The kind of wild disparity between the Republican and independent/Democratic vote that we saw 12 years ago just won’t exist today. Still, there’s now audio evidence of Santorum trying to recruit Democrats to help him against Romney – something the Romney forces will be happy to remind Republicans about going forward.

Shares