As he demonstrated in what amounted to an unofficial Republican nomination acceptance speech this week, Mitt Romney’s basic pitch to voters boils down to this: If you don’t think the economy’s in good shape, don’t ask questions – just vote the guy in charge out.

Barack Obama’s message is more nuanced, and context-dependent. “Now, the burden on me is going to be to describe for the American people how the progress we’ve made over the past three years, if sustained, will actually lead to the kind of economic security that they’re looking for,” he told Rolling Stone in an interview published this week.

Romney, obviously, has the easier sales job, and the powerful superficial appeal of what he’s saying helps explain why he’s so competitive with the president in polling, despite the serious image problem that Romney and his party both have. The Romney team believes that the basic formula that produced the last one-term presidency – George H.W. Bush’s – applies in 2012: broad economic anxiety and pessimism and an opposition-party candidate who focuses on the economy “like a laser beam.” In his speech this week, Romney even employed a modified version of the signature phrase associated with Bill Clinton’s 1992 campaign, declaring, “It’s still about the economy, and we’re not stupid.”

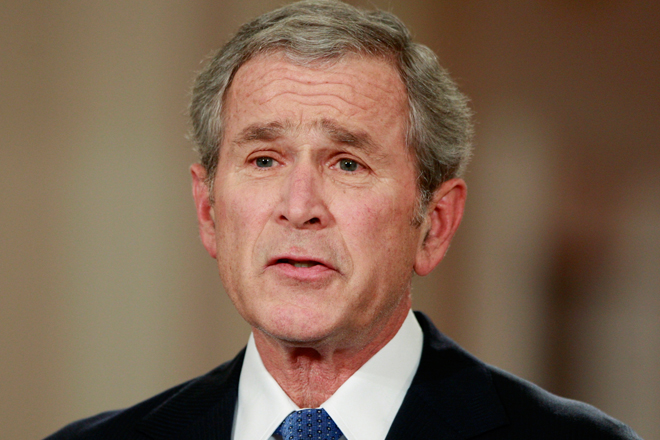

Assuming there’s no significant economic improvement between now and Election Day, Romney’s approach should be enough for a lot of swing voters – enough, at least, to make the race very close. The question is whether Obama can convince a critical chunk of swing voters to look beyond Romney’s prescription and take a broader view of where the economy stands. This is where Obama’s White House predecessor comes in.

For understandable reasons, Romney and his fellow Republicans have committed themselves to never mentioning George W. Bush and to acting as if their party didn’t control the White House for most of the last decade (and Congress for half of it). But Obama has been bringing up the Bush years, as he did with Rolling Stone:

Their vision is that if there’s a sliver of folks doing well at the top who are unencumbered by any regulatory restraints whatsoever, that the nation will grow and prosperity will trickle down. The challenge that they’re going to have is: We tried it. From 2000 to 2008, that was the agenda. It wasn’t like we have to engage in some theoretical debate – we’ve got evidence of how it worked out. It did not work out well, and I think the American people understand that.

There’s something to this. A poll a few months ago found that more than half of voters – 54 percent – still say that the country’s economic woes are primarily Bush’s fault, with only 29 percent blaming Obama.

This represents a potentially key difference from the ’92 scenario that Romney is trying to replicate. When Bush 41 sought reelection 20 years ago, he couldn’t claim that he’d inherited an economic catastrophe. He’d taken office with unemployment low and had watched it skyrocket thanks to the early-’90s recession. Nor could he credibly say that the mess was the product of the other party’s mismanagement. By ’92, Republicans had controlled the White House for 12 consecutive years – and 20 of the previous 24. This allowed Bill Clinton to run not just against the incumbent president’s stewardship, but an entire generation of Republican leadership.

“The thing that makes me angriest about what has gone wrong in the last 12 years is that our government has lost touch with our values,” Clinton said in his convention acceptance speech, “while our politicians continue to shout about them.”

Later in the speech, he said: “The Republicans have campaigned against big government for a generation, but have you noticed? They’ve run this big government for a generation and they haven’t changed a thing. They don’t want to fix government; they still want to campaign against it, and that’s all.”

It’s hard to believe now, in this era of Gipper hagiography, but the popular consensus in ’92 was that the high unemployment, soaring deficits and sagging confidence were the legacy of the Reagan years – and that Bush represented a continuation of the same policies and the same results. Bush pleaded that the domestic economy was the victim of a global slowdown and that the worst was in the rearview mirror and tried to blame the Democratic-controlled Congress, but 12 straight years of single-party White House control created a powerful popular appetite for change.

Obama, on the other hand, remains a personally popular president, and memories of the complete financial meltdown that preceded his presidency – and of the man who was in charge when the meltdown happened – are still relatively fresh. It seems possible this could buy him time with just enough swing voters to hold off Romney. The Bush effect is probably impossible to quantify, but there is some evidence of a small but real “benefit of the doubt” bonus for first-term presidents.

Obama’s challenge remains formidable, especially if current economic conditions linger, or worsen. Public opinion seems perpetually to exist in the present tense. Even among swing voters who remember Bush and understand what happened in 2008, there’s a strong impulse to find a way to blame Obama, even if it requires rationalizing. But you have to go all the way back to FDR and the Great Depression to find a president who came to office against a comparably traumatic economic backdrop. We probably don’t know yet how significant (or insignificant) the Bush factor will be.