I must’ve been eight or nine the one time my dad took me along to meet Bart. This was somewhere near Tompkins Square Park. What I recalled was a shaggy shock of blue hair, and feelings of both elation and terror: On the one hand thrilled to be old enough to be taken along one night to the city to meet a guy with blue hair, and on the other frightened of the jagged dark in the Alphabet City of the late '80s. In my memory Bart looked like Warhol, but maybe that was just part of the dream pedigree I had for my dad, the one that looked to White and Genet and not "Will & Grace." But I did think that my dad once said he’d gone with Bart to sell drugs to Allen Ginsberg, so maybe in this case my retrospective fantasy — that if he’d had a secret life, it could at least have been an exciting one, something worth escaping his surface life for — was accurate. I remembered hearing for the first time about AIDS, and I remembered my dad walking around for some months, maybe years, as though accompanied by ghosts. It was selfish and obscene for me to look back and want his secrets, the secrets I’d come here to try to clear up, to have hidden amazing things: It meant I have at best ignored and at worst aestheticized the fact of what must have been unimaginable pain. Like any gay man of his age, he’d watched a great number of his close friends die of AIDS, but unlike many of those men, he was not able to talk about it to the people closest to him, the people he lived with. Maybe the reason he liked "Will & Grace" and not so much White and Genet — though, now that I think of it, I did give him "The Married Man" once and he told me it was the best novel he’d ever read — was that all he wants now is to be normal and happy. He wanted to marry Brett and drink boxed wine and take Yoshi out for walks and watch "Mamma Mia!" until their DVD player caught fire. I myself had never been less than loathsome on the subject of "Mamma Mia!" and I felt terrible about it, but I didn’t want to digress into overemphatic apology, and I would stand by my derision of "Mamma Mia!"

It was around the time that Bart died of AIDS that things began to get really bad. That was when my dad had dyed his bangs platinum, which didn’t go over so well with the congregation he then served and would not serve much longer. This was around the time that in a fifth- or sixth grade art class I made a painting of a male seraph sealed in a black box in the center of an otherwise Edenic scene and wrote, in black block letters across the top, Who are you forcing into the closet? A nasty debate ensued over whether it could go up on the middle-school wall. I can only imagine that my dad had gone to see "Angels in America," talked about it at home. It is, however, also possible that this episode lends credence to his idea that I knew all along. He talked about theater a lot back then and gave me John Simon’s reviews to read when he thought they were particularly savage. They were confusing for a 10-year-old. But I liked waking up in the morning to clippings he’d left under my door. Sometimes he said he’d wished he’d been an actor, had become a rabbi less for the liturgical than for the performative aspects of the job, and because he’d so much liked spending time in Israel and speaking Hebrew. This was also around the time my dad started to seem arbitrary and punitive, when he would come home late and throw all my CDs down the stairs because there was unfolded laundry on the dining room table. I began then to understand there were sealed-off swaths of my dad’s time, and that the patterns of his emotional climate could neither be predicted nor accounted for.

“Bart was the first person I ever told I was gay. That was in 1986. I was taking social-work classes one night a week in New York. It was raining and I was headed downtown in a cab. The cabbie asked if I minded if we picked up a guy standing in the rain. He got in the cab and looked at me and knew right away, and we went out for coffee. He was the first person I could talk to openly.” Again, it’s hard to get his stories straight (again: so to speak). When he told me, at nineteen, that he knew I already knew he might prefer men, the backstory went like this: In the early to mid-'90s he discovered he was bisexual but chose to live with this knowledge and remain in his marriage. In 1997 or 1998, after meeting Brett, he began to envision a different sort of life. It was time for him to do something for himself for a change, put himself first. This meant the license to make up for lost time. There was a lifetime of Palm Springs poolside drag parties to catch up on.

After five or six years he was telling a new version, or hinting at one. There were salacious allusions to the loss of his virginity, wistful ones to his first love. But these comments felt more like boasts than invitations to further inquiry. Under the pretense of closeness it expanded the distance between us. His unexplored asides reminded me of how much I didn’t know, how much had happened that had nothing to do with me. “I had a boyfriend who sold drugs to John Lennon. Someday I’ll tell you about that,” he’d say, and then smile and trail off. These conversations made me angry. No, more than that, they made me feel stupid, gullible, excluded. He’d deceived me, deceived us, and then everything he ever said could only appear in that light. His clumsy attempts to clue us in only ever deepened my sense of deception. The implication of this second story was that he’d been with men before and then decided—in a way that somehow suggested a proleptic sacrifice — to martyr himself with a straight life. Twenty years later he found the strength to live once more for himself. His stories always ended with this new resolve, a moment in which he at last was able to swear off his burdensome obligations.

I told people, when they asked me about my expectations for Rosh Hashanah in Uman, that what I thought was going to happen — what I wanted to best-case-scenario happen — was to hear the third version of his story, the one where Micah and I found out he’d been with men all along. I wanted to hear this in part because I wanted to feel undeceived. Of course, though, there’s no such thing as making yourself undeceived; I suppose I wanted the deception confirmed. Contained. Laid bare. There had always been rumors. My freshman year in high school I heard third-hand from a classmate that my father had told someone he was gay, or maybe had been seen at a gay fundraiser. What was worse than not knowing was that other people did somehow.

“I told Max in 1988. I went to Philadelphia on business and I stopped into his office at the thermocouple plant when I knew I only had 10 minutes to talk. I told him and I walked right out before he could really respond. He didn’t know what to say. He didn’t say he knew all along. I think he was stunned.”

“Did Max seem accepting?”

“I don’t know. I didn’t give him a chance to say anything. I told my mother a few months later. By then Bart was taking me out and introducing me to people, showing me around, taking me to the Roxy.”

“So you and Bart were involved, then?” I tried to keep my voice even.

“No! Never. That first time I met him, over coffee, I made a pass, but he looked at me and said I was craaaazy, that he’d have to be crazy, that I had a wife and two little kids at home. He didn’t want to get involved with that. So we were only ever friends, which was better anyway, because what I needed then was a friend I could talk to about things I’d never talked to anybody about.”

“I want to know how you were feeling then. Did you wake up in the morning at home and look around you and think, This is not really my life?” I thought of David Byrne, This is not my beautiful house . . . this is not my beautiful wife.

“No. I wanted that life too. I wanted to be married. I loved you guys, and I loved your mother, and I know you don’t believe me but I still love your mother. I never thought about doing anything differently.”

“But didn’t you feel regrets? Don’t you feel regrets now? Wasn’t it hard to live this double life?” I was baiting him a little. It seemed important to me, had seemed important to me for a long time, to know he regretted everything, he was sorry for everything, he wished it had been otherwise. I do not know how to account for this but there was some part of me that wanted to hear he regretted we’d been born.

“Gay guys compartmentalize. It’s just what you have to do. No, it wasn’t that hard, mostly, and I really have no regrets at all. At that point in my life I had no way to imagine anything else. In 1974 there was simply no openly gay role model in my life that might have shown me a way to live differently. And I never didn’t want to be married. I never didn’t want to have my family. I’d always wanted a family.”

“So, what made you finally stop? What made you decide it was time to come out. Also, wait a second, what’s 1974?”

“I wanted to give your mother her life back.” Micah and I exchanged our long-practiced well-that’s-bullshit look. The one thing we knew we were absolutely not going to talk about was our mom, because whatever he was possibly going to say was going to make us angry. “And I wanted to do something for myself. I wanted to put myself first.”

“But weren’t you already putting yourself first, at least half the time? In your New York life? In whatever was going on in the other compartment? Weren’t you number one there?”

“I guess I wanted to put myself first successfully.”

“And you couldn’t have done that before? And you never regretted not having done that before?”

“No, really, Gideon. I am not lying to you. I couldn’t and didn’t.”

We stood over fragments of Jewish gravestones strewn amid the clumps of dead grass. This was all a little much, the broken gravestones, the pogrom detritus. I was surprised. I’d always imagined this was going to be a conversation about his regrets, about the psychic strain of having committed to a life that didn’t feel like yours, that didn’t feel like what you’d wanted or chosen for yourself. I was prepared to be sympathetic to him — the volatility, the punitive tendencies, the absences — if I could hear from him that he’d been driven out of his mind by the suspicion that his real life was happening elsewhere. If he’d had two lives, I could have been at the very center of one and at the very periphery of the other, and I would have known to take only the first one personally.

But my dad was making it clear that he did not feel as though his real life had been elsewhere. I had suggested it must have been hard to have two lives, and he’d agreed, but he didn’t actually have two lives. Nobody has two lives, just like nobody lives an imitation life. He had one life, a real life, and in that one life he’d told a lot of lies and kept a lot of secrets, and it was never clear if I was — if we were — at the center or on the margin. I’d never wanted to think of him as a liar. I’d never wanted to feel like someone who could be so easily lied to. I’d wanted him to have regretted a lot of things because that might also have meant he hadn’t lied about a lot of things, and if he regretted them, it meant he was acknowledging he hadn’t made the best decisions — even if he continued to think of the consequences of those decisions in terms of his own life, not in terms of ours.

But I could hardly deal with his regret, either. If he was a liar, I was an idiot; but if he was regretful, Micah and I had been burdens. It would be better to admit I’d been deceived, deceived by the person in the world I most wanted to be like — the navigator who knew all the long-cut (mileage-saving, time-adding) hypotenuses on local back roads; the only parent who was willing to drive around on empty unplowed streets after a blizzard to pick up all of our friends on the way to the secret sledding hill he’d found; the former college radio DJ who’d always been so endearingly baffled by the part in “MacArthur Park” (the Donna Summer version, of course) where someone leaves a cake out in the rain; the news junkie who came to dinner with labeled manila folders for each of us, full of relevant and absurd clippings from the five daily newspapers and three weekly magazines he read; the theatergoer who loved the savagery of this John Simon guy and took me to off -off -Broadway productions in dingy Greenwich Village basements when the other suburban parents made the thirty-minute trip into New York once a year to go skating at Rockefeller Center; the rabbi who seemed so proud and calm and authoritative giving demanding High Holiday sermons in which he alluded to the lyrics of Queen and Procol Harum, who made me so proud to be the rabbi’s son, progeny of moral authority, near to a moral center, even if I had so little practical knowledge of Judaism — than to continue to feel as though my existence as the rabbi’s son had thwarted his chance at having the life he deserved. I did not want to have to imagine my childhood and adolescence as an obstacle. I wanted to be able to think of his happy gay life now in terms other than contrastive freedom.

We paused under a lone shade tree and looked at a few sheared-off gravestones with Hebrew names. We picked our way over the uneven ground. Micah had grown completely quiet. He’s got other issues, or maybe he doesn’t have any issues at all. He doesn’t remember as much as I do. He’s much quicker to let go of things.

“But, Dad, wait a second.” I felt as though we’d skipped something here, that whatever had actually been going on — this other life we’d started to talk about — was being acknowledged without being admitted. If he wasn’t going to talk about regret, then we were going to talk about lies.

“You said that Bart was the first person you ever told you were gay. But didn’t you have relationships with men before that?”

“Well, there were always physical things. Bart would take me out and I’d find gratification. After a certain point you just get tired of masturbation, you know? But there was nothing emotional, nothing serious. It was all just physical. After all, don’t forget, I was married.”

I hadn’t forgotten. This felt so unfair. If your dad casually admits to having serially cheated on your mom for your entire childhood with other women, you have the right to be furious. If your dad casually admits to having serially cheated on your mom for your entire childhood with men, you’re supposed to be sympathetic. Or I felt as though I had to be sympathetic. He was such a convincing martyr. I hadn’t been allowed — hadn’t allowed myself — to be furious for so long, because I’d believed the story of sacrifice my dad told. I wanted to feel furious now, but all I could feel was a surprising sense of gratitude. I felt as though these casual admissions had fixed something for me, both in the sense of repair and in the sense of the record I’d come to get, and I was somehow finally understanding where I stood in relation to him.

“No, I mean, that’s interesting,” I said, eager to keep this going, “but that wasn’t quite what I meant. I thought once when you were visiting me in Berlin you made some comment about your first boyfriend, your first love. And a minute ago I thought you said something about 1974.”

“Oh, well, that was before my marriage. That was Rocky.”

My dad stopped and smiled his least melodramatic smile. The imminent unveiling of these memories made the moment seem staged, as if he’d been given a script and asked to play the part of a father overcome with nostalgia. He looked engulfed, totally convincing. I didn’t know if I wanted to hear what was coming. When so much has been kept secret, it’s impossible to know what you do and what you don’t want to know, what ought to be shared and what might best be kept to oneself.

“I was twenty-one and in Jerusalem alone. I’d wanted to go abroad to Russia but it was hard to do that in 1974, and my plans fell through at the last minute. So I scrambled and went to Israel instead. If I’d gone to Russia, I probably would’ve ended up in the CIA or the State Department or something, but as it was I went to Israel and I met Rocky, and I loved Hebrew and I loved Israel and I thought, I’ll just stay here and become a rabbi. Rocky was in his forties. He was an ophthalmologist. He once fitted Golda Meir for contact lenses.” My dad laughed.

“Where did you guys meet?”

“At the Turkish bathhouse, which was the only thing like a gay scene in Jerusalem in the seventies. You could go and, you know, have sex with young Arab boys.” I hadn’t known that. Micah, I am willing to guess, hadn’t known that.

“Rocky had money, and he had this great apartment, an entire floor on the fourth floor of a building on King David Street, right near the YMCA and HUC,” the reform rabbinical seminary where my dad met my mom a year or two later. “He had such nice things, such beautiful furniture, wonderful rugs. Exquisite taste. I was a kid and away from home and he took care of me.” My dad looked so sweet and serene as he remembered this other place, this thing it’s tempting to call a previous life. We all kept stumbling on the shards of pogrom gravestones underfoot.

“When did it end?”

“I started rabbinical school the next year and met your mother and that’s what I wanted then, so I broke it off with Rocky.”

“And there was really no way for you to imagine living a gay life then? No role model?”

“It was unimaginable to me.” I wondered why Rocky himself didn’t count.

“How did he take it when you broke up with him?”

“To be honest with you, I can’t remember. I hadn’t made any promises to him. I was really just a kid. But then” — he paused — “I went and saw him once, years later, maybe 15 years later, I looked him up when I was back in Jerusalem.” We’d gone to Israel as a family in 1988, when I was eight and Micah was five. Micah had been run over in the street by a kid on a bike. “I can’t remember what we said to each other, though.”

“I’m sad that you were never able to tell us these stories. I’m sorry you weren’t able to tell them to us growing up.” I was a little shaky, but it was a lot easier to hear stories that predated my mom than the other ones he’d been telling. We’d gone back past the mikveh and were walking by a low-slung trailer soliciting donations for a “Fond Rising for the Monuments to Victims of Holohost.” I wanted to hear these stories, didn’t want to hear these stories, felt bad about needing to hear them, felt bad about not wanting to hear them, doubted that even this third version of his life was totally honest, angry to have to feel doubt, very sorry for my mom — sorry for my mom both because of what she went through and because it felt like a kind of betrayal to feel so good that talking to him about all this stuff made him feel so good.

It is nothing special that my dad had a life separate from me, or that he kept secrets; this is something all parents do — straight ones, scrupulous ones — and it’s what we grapple with, to varying degrees of success, our whole lives. What’s unusual about my relationship to my dad’s life is not that there were things about it I didn’t know because he was gay. It’s that I was able to indulge the fantasy that he kept secrets only because he was gay, that if he had been able to be openly gay he would’ve shared his entire life with me and I always would have known exactly where I stood. At a certain point other people have to understand that parents keep secrets, that parents close parts of themselves off to their children, because that is what parents do.

What was I getting out of learning this now? In part, I wanted to hear him tell a story about his life in which he claimed some responsibility for the way things had turned out, rather than a story in which he was first in thrall to social mores and later in thrall to biological urges, in which the pretexts had shifted but the irresponsibility had remained. In which he’d never simply said, “I did it because I felt like it.” I wanted him to be a father who provided an example of how to live a life that he could describe as more than just a series of obligations to others, a life in which he did more than just hurt others under the cover of conflicting obligations. We follow St. James to the end of the world, and follow Kōbō Daishi in his path around that horrible island, because we want to associate ourselves with their absurd decisiveness. We want to inherit from them the ability to make our own absurd decisions, even when that means taking the damn train to the karaoke party. But we also want to know that when people get hurt it’s because they had to be hurt. We also want to be reassured that the eight innocent sons of Emon Saburō had to die in order for justice to reign. That the promises he made had to be broken, that he could not possibly have done what he said he was going to do.

This longing for his decisiveness helped explain my preoccupation with the history of his sexuality. There are very few examples in modern adult life of the successful instantaneous transformation, the switch that is flicked to make everything new — the fantasy of the transformative arrival in Santiago — but the example of coming out is one of them. Which I think is why I’d for so long kept such careful tabs on what story he was telling whom when: I wanted to nail down the moment of his coming out, with the hope that if I could pinpoint that transformation I could . . . I don’t know what I could do, I would just feel better, would be able to look to him as a model of resolve. I wanted to identify the moment that he decided to live for himself despite the costs involved. I wanted to know where he stood.

I wanted him to have been able to say, “I did this because I felt like it.” I wanted that example. But I didn’t want him to stop saying, “I did it because I had to.” I wanted that example too. It is an intolerable conflict to want your father to have been resolute and unapologetic and also need him to have not hurt you, to want to take nothing personally and everything personally.

What I was finally coming to understand here was that there was no such moment, no grand gesture of repudiation, no final grace, no scene of coming through the Wall, nothing you can do now that makes all future cost considerations fall away, no way to know what you might regret. There was just a long muddle in which he’d had terribly conflicting desires and had been doing his best to resolve them. I still do not believe he’s ever reckoned with the costs — or perhaps he’s reckoned with the costs he paid, but not the costs borne by others. But in Uman I accepted, in a way that felt new, that he had been in a crisis, and that he had also been doing what he wanted.

I’d drawn exactly the wrong lesson from his surfeit of contradictory stories. I thought it was just his standard obfuscation. But it was just his ongoing and incomplete attempt to tell a story about his life that made everything make sense.

There is no such thing as knowing, once and for all, where you stand with someone. Life has no fixed points. But pilgrimage does; that is the point. And the fixed points of a pilgrimage allow people to exist for each other in motion. There is no such thing as coming out.

In Tokyo, three months later, we’ll be having a great time — a really remarkable time — at Thanksgiving dinner and I’ll ask Brett what he thinks about the idea of coming out.

“I’m 48,” he’ll say, “and I’ve been in the process of coming out for 30 years.”

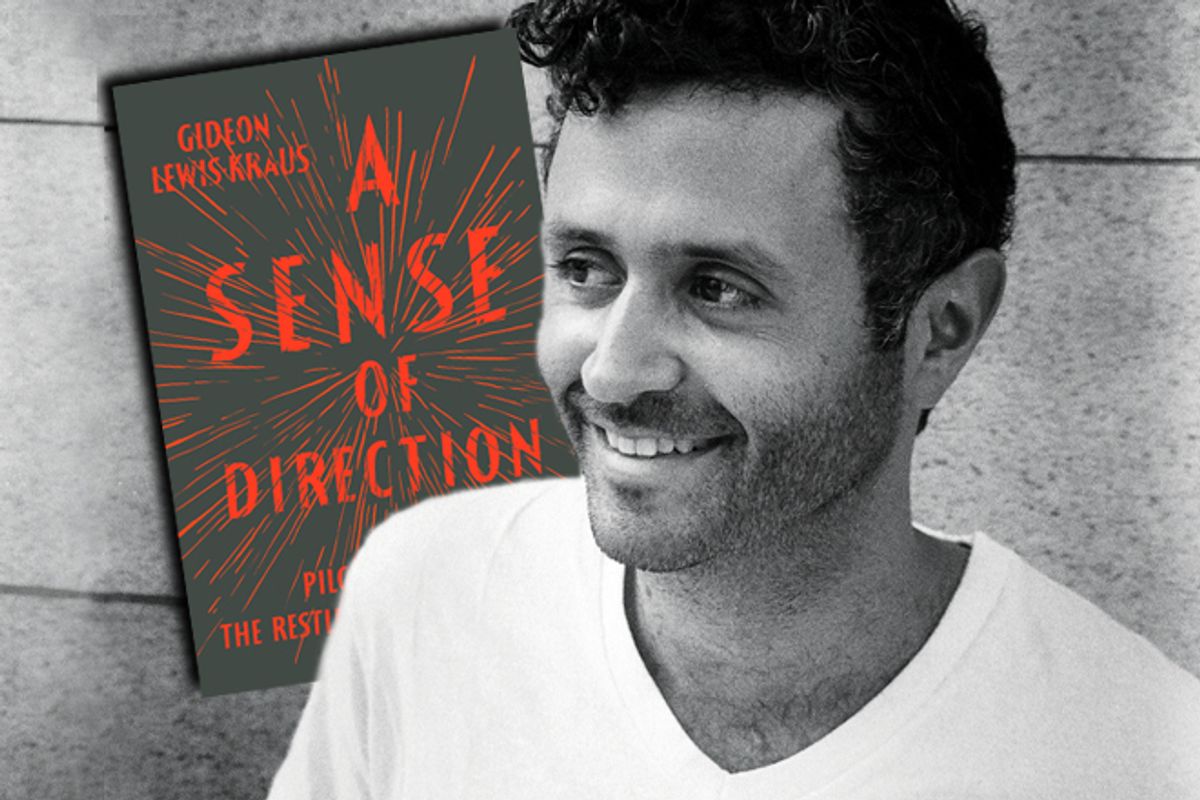

From “A Sense of Direction: Pilgrimage for the Restless and the Hopeful” by Gideon Lewis-Kraus, to be published on May 12, 2012, by Riverhead Books. Reprinted by arrangement with the author.

Shares