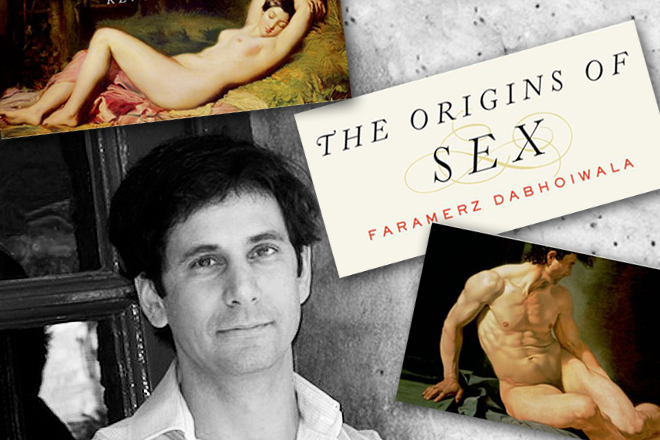

Academic history — the kind backed up by piles of primary-source research and hedged with cautionary remarks — is often useful, but rarely fascinating. Most of it, however, isn’t about a subject as perennially engaging as Faramerz Dabhoiwala’s. The Oxford historian’s new book, “The Origins of Sex: A History of the First Sexual Revolution,” describes how sex became modern in 18th-century England, a transformation that explains “the profound chasm between our present attitudes to sex and those that prevailed for most of western history.” We tend to think of sex as something primal and unchanging, but as Dabhoiwala tells it, nothing could be further from the truth.

“The Origin of Sex” begins with an anecdote from 1612. An unmarried couple accused of fornication and bastardy (producing an illegitimate child) were dragged before the magistrates. They were convicted, then sentenced to be stripped naked to the waist, “whipped from the Gatehouse in Westminster unto Temple Bar” before the jeering public and then banished from the city — severed from their families, former friends, and previous occupations. Publicly shamed and condemned, their lives as they knew them were over.

As extreme as such penalties sound, Dabhoiwala argues, they were generally approved by the populace. Even “members of the gentry and aristocracy” would be punished for “adultery and other sexual crimes,” and that was fine by their neighbors, who saw the stern policing of sexual behavior as a communal as well as a church responsibility. By contrast, a little over a hundred years later, Londoners would be founding hospitals to rescue and reform “fallen women” and gobbling up printed accounts of the exploits of famous courtesans. It was a huge change: from a culture of what Dabhoiwala calls “sexual discipline” to one where many viewed sexual pleasure as natural, something you couldn’t really expect people to forgo — at least, as long as those people were heterosexual men of the higher classes.

The causes of this change are numerous and complex, and it’s particularly difficult to explain because most contemporary people assume that everyone in the past saw sex much as we do now — albeit, with a greater degree of “repression” and a longer list of forbidden activities. Dabhoiwala’s trickiest task is presenting a clear enough picture of pre-Enlightenment conceptions of sex that you can appreciate how profound the 18th-century revolution was.

You may have heard, for example, that in the Middle Ages women were regarded as the more erotically insatiable and adulterous gender. That’s true. However, this was not because the medievals thought women felt more lust than men; everyone was assumed to be subject to more or less the same amount of sinful desire. Women, however, were supposed to be weaker than men morally, less able to control and subdue their unchaste urges. The medieval concept of manliness owed much to the classical model, with its celebration of self-mastery, but with an added Christian suspicion of sex as fundamentally and problematically worldly, even within matrimony. As St. Paul put it, “It is better to marry than to burn” — but better yet to do neither.

All ages have their sexual renegades and bawdy humor, but looking at these doesn’t always give you a sense of how most people lived and thought. Dabhoiwala uses the rate of illegitimate births as a rough guide to just how much adulterous sex was going on at any given time. He also examined court records of trials for adultery, bastardy and other sexual transgressions. The medieval model of sexual discipline, it turns out, was quite effective, and the Adultery Act, passed by the Puritan-dominated Parliament in 1650 and making adultery a capital crime, was even more so. In 1650, only one percent of all babies were born to unmarried women. By 1800, it was 24 percent, and furthermore, 40 percent of women getting married were already pregnant.

What happened between 1650 and 1800? According to Dabhoiwala, the 1700s saw a “momentous ideological upheaval” when it came to the notion of sexual liberty. The Reformation permanently undermined the authority of religious leaders; if the Catholic Church was wrong about this or that point of faith, then couldn’t any church also be wrong in its prohibitions against a particular activity or feeling? It was a shift, ultimately, from the belief that outside agencies ought to impose morality on citizens in order to protect the community as a whole from dangerously immoral behavior, to the idea that “public authorities had no business meddling in people’s personal consciences, and that this extended to their moral choices.”

These Enlightenment ideals infused the American Revolution and still animate our discussions of such issues as gay rights. But if they were embraced by many 18th-century intellectuals and wealthy men, they were problematic when it came to women, whom those men preferred to go on treating like property. At the same time, the blossoming of print media — from newspapers to broadsheets and pamphlets to books — gave women writers an unprecedented access to the conversation. They pointed out that women suffered the consequences of men’s sexual liberty, be it in the form of venereal disease, pregnancy or disgrace. From these and other contradiction sprang the relatively new notion that women “naturally” experience much less sexual desire than men and that an imbalance in the erotic economy is the intractable result of rapacious male lust and female sexual passivity.

It’s no surprise, then, that the same period saw a boom in prostitution, or that prostitutes and their fates became a widespread preoccupation. Once viewed as simply wicked, they were now commonly seen as the pitiable (if still sinful) victims of male seducers. A particularly valuable aspect of “The Origins of Sex” is its treatment of the element of class in this equation. Feeling entitled to sexual pleasure when they could get it, high-status men often considered servants and other working-class women as their rightful prey, whether the women were willing or not. The motif of female virtue under assault by a male libertine became the predominant theme of the first English novels; Samuel Richardson’s “Pamela,” for instance, depicts a virginal maid’s heroic resistance to the overtures of her employer.

Meanwhile, the emergence of the first real mass media made celebrities out of fashionable courtesans like Kitty Fisher, whose doings, outfits and witty remarks were avidly covered by the press. When Fisher fell off her horse and was aided by a “gallant” in a London park, the incident was recounted in engravings and humorous verse. The term “pornography,” or “the writings of prostitutes,” emerged at this time because many of these women wrote and published their own accounts of their lives and loves. (And sometimes they made a little on the side by taking bribes from customers who wanted their names left out.)

The Enlightenment was a complex social and philosophical phenomenon and of course the old views of sexual morality never entirely went away. Yet, as Dabhoiwala observes, in general the Western conception of sexuality as something uniquely personal, a key element of one’s identity and a matter of private, rather than public conscience, was born in the 1700s. It has changed far less in the three centuries that followed than it did in that 100-year span. “The Origins of Sex” tracks that momentous shift up to the beginning of the Victorian era. It’s a hugely ambitious book, and one that makes few concessions to, say, the popular appetite for histories constellated around personalities (like Stephen Greenblatt’s “Swerve”). But Dabhoiwala’s writing is lively, his reasoning rigorous and his respect for facts exemplary. And his story is irresistible, a portrait not only of a revolution in sex, but a revolution in the way we view ourselves and our place in the world.