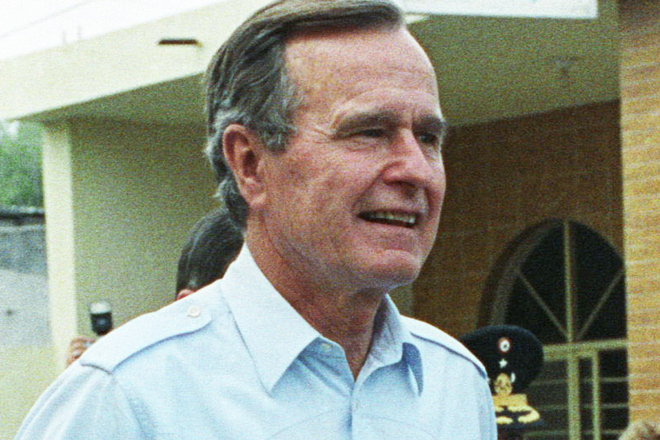

“41,” a new documentary about George H.W. Bush set to debut on HBO Thursday night, is a political film that isn’t very political. It’s the story of the former president’s life, told only in his words, without much context and with no critical commentary.

We see, for instance, that he ran for president in 1980, but we’re never reminded that he did so as a pro-choice moderate who ridiculed Ronald Reagan’s supply-side agenda as “voodoo economics.” Nor is it mentioned that he opposed the Civil Rights Act of 1964 during his first campaign, that his pick of a vice president prompted widespread ridicule and raised concerns about his judgment, and that he won the White House in 1988 with an ugly campaign that challenged his opponent’s patriotism and featured its share of race-baiting.

For the most part, this isn’t a problem. There is much to admire about Bush the man and much to respect about his presidency, and the film isn’t trying to create a definitive historical record; it’s simply offering viewers a chance to watch a public man not known for his introspection reflect at length on his 88 years of living. It’s well worth a viewing.

But Bush does make an observation that is very relevant to the historical record and to today’s paralysis in Washington. It involves the most consequential domestic action of his presidency: the 1990 budget agreement.

As a candidate in ’88, Bush had made a show of promising to resist any effort by Democrats in Congress to increase revenues. “They’ll push and I’ll say ‘No,’” he’d said, “and they’ll push again and I’ll say to them, ‘Read my lips: No new taxes.’” Confronted with the reality of lingering Reagan-era deficits as president, though, Bush recognized the need to go back on his word. But in so doing, he undermined his credibility with voters and prompted a full-fledged revolt from conservatives (who were led by an ambitious and ruthless House minority whip named Newt Gingrich) and a primary challenge from Pat Buchanan in 1992.

In “41,” Bush is asked by an off-camera voice if he regretted any of it. “Nope,” he replies. “It was right.”

History smiles on this assessment. Along with Bill Clinton’s 1993 budget, the deal that Bush struck in 1990 established new tax rates that, once the economy revived in the middle and later years of the decade, produced a revenue windfall. By the time Clinton left office, the country was running surpluses and the elimination of the entire national debt was within sight.

But Bush hasn’t always been this proud of what he did. Rather than standing by his actions, when he ran for reelection in 1992, he actually repudiated the ’90 budget, telling Americans that he’d made a mistake and regretted ever doing it.

“I should have held out for a better deal that would have protected the taxpayer and not ended up doing what we had to do — or what I thought at the time would help,” he said during one of the ’92 debates. “So I made a mistake. I — you know, the difference, I think, is that I knew at the time I was going to take a lot of political flak, I knew we’d have somebody out there yelling, ‘Read my lips.’ And I did it because I thought it was right — and I made a mistake.”

Whether Bush actually believed this at the time is unclear, but it’s worth remembering that the unanimous consensus on the right in ‘92 was that the ’90 budget had failed, since deficits were still soaring. There actually was a reason for this: The economic downturn of the early ‘90s had reduced overall tax revenue, spoiling the deficit reduction projections that had been envisioned. But Bush didn’t try to make this case during the campaign. Any American listening to him would have believed that his effort to arrest deficits with a tax increase had failed.

There was a serious consequence to this, because it allowed the anti-tax absolutists in the GOP to claim vindication. The idea that taxes should never be raised for any reason became popular in the GOP in the late 1970s and ‘80s, but it was only after the ’90 saga that it became an article of faith. As a result, when Clinton proposed his tax hike/spending cut deficit reduction plan in ’93, not a single Republican was willing to vote for it, nor have any Republicans been willing to compromise on the issue since.

You can draw a direct line from ‘90 to today, as congressional Republicans refuse to even consider raising taxes on the wealthiest Americans in the face of a $15 trillion debt. Their adamance has made any substantial compromise between the executive and legislative branches impossible these past two years, and threatens to do the same next year if divided government is still the rule.

When Bush called the tax deal a mistake during that ’92 debate, Bill Clinton jumped in to correct him. “The mistake,” Clinton said, “that was made was making the ‘Read my lips’ promise in the first place, just to get elected, knowing what the size of the deficit was.” As he lives out his political retirement, Bush is more than justified in expressing pride in what he did in 1990. But he would have been equally justified in doing so at the time – and it might have mattered more if he did.