When Walter White shaved his head midway through the first season of “Breaking Bad,” it was a preemptive strike. Eyeball-to-eyeball with the tenacious threat of his cancer treatment, he took action. He sheared his hair before chemotherapy could take it from him. He beat cancer to the punch.

It was a move — proactive, tactical — that defines this increasingly complex character. It signaled a turn away from Walter White the frazzled father and high school science teacher (introduced in the series premiere hapless and sockless, stumbling around the New Mexico desert in blousy white underpants) to Walter White the would-be criminal kingpin, reborn as the menacing “Heisenberg” — narrow-eyed and calculating but above all else, bald. Because for all its other, sundry qualities, “Breaking Bad” is certainly the baldest show on television.

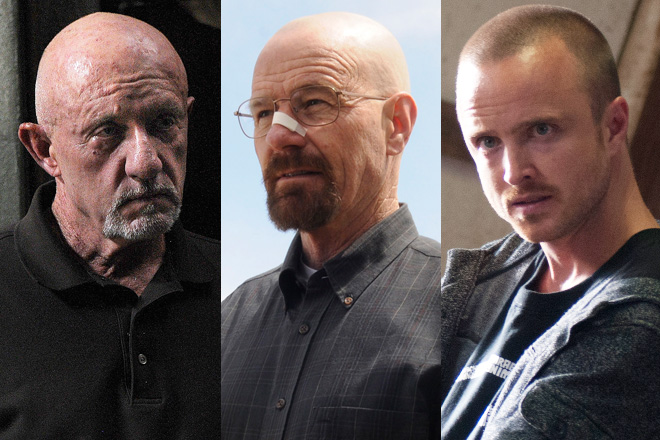

Let’s quickly inventory the show’s selection of partially, cosmetically or fully follicly challenged characters. There’s Bryan Cranston’s Walter, of course; his close-clipped junior partner Jesse Pinkman (Aaron Paul); Mike the Cleaner (Jonathan Banks), the recent addition to their criminal triumvirate; Walt’s Kojackian DEA brother-in-law, Hank (Dean Norris); and, as of this season, the crippled buffoon and terminal thorn-in-the-side Ted Beneke (Christopher Cousins). And the guy who sells Walt the heavy artillery in Season 5’s opening scene? Bald.

In the bleak moral universe of “Breaking Bad,” hair — on men, at least — seems patently ridiculous. It’s an indulgence in vanity, an impractical affront to the balmy Southwestern sun. (To wit: Dig the pathetic comb-over of Walt’s ambulance-chasing attorney, Bob Odenkirk’s Saul Goodman.)

For a show that deals so directly, and often very elegantly, with the subject of masculinity, with the idea of an assumedly “good” man turning to criminality and violence to support his family, a perverse through-the-hourglass riff on “Father Knows Best,” “Breaking Bad” is distinguished by its baldness. Just as Walter flipped the script on chemotherapy by defensively owning his diagnosis, so too “Breaking Bad” revises the prevailing Samson-esque cultural connotations between healthy hair and virility, and between baldness and inadequacy.

If “Breaking Bad” isn’t reversing existent stigmas surrounding baldness, it’s at the very least responding to changing attitudes. After all, we’re a decade or so out from the Rogaine-slathered, Hair Club for Men culture of the ‘90s. Then, hair tonics, wigs and other quick fixes were big business. And big business translated into pop cultural panic.

Who can forget the moment when George Costanza struts into the “Seinfeld” apartment festooned with a ludicrous toupee? Or when Homer Simpson’s chemically induced hair growth got him kicked up the corporate ladder? The associations were clear: Hairlessness suggests powerlessness, a comically pathetic quality. You can read these ebbing hairlines like those fortunetelling tea leaves. And the forecast was never good. For someone like “Seinfeld’s” George, constantly at odds with the cruelty of fate, the universe seemed to nastily avenge itself upon his bald head.

The more pointed anxieties about male pattern baldness may have been alleviated somewhat by the popularity of Viagra and similar over-the-counter enhancement drugs. After all, who cares about the symbolic associations between hairlessness and between-the-sheets dynamism when a real-deal cure for impotency is just a popped purple pill away? In TV, however, they seem to persist.

Tony Soprano, premium cable’s paterfamilias, may have been stout, snub-nosed and chrome-domed. But his receding hairline (and, as the series advanced, expanding waistline) shaded his loss of power in his domestic and criminal empires. As much as Tony’s figure was imposing — almost like a modern update of Judge Holden in Cormac McCarthy’s “Blood Meridian”; a mountain of flesh, ancient hairless as Father Time, ordering the American West with violence and perverse, nonscientific note-taking — it also allowed him to pass as the North Jersey any-dad, slouched in front of the TV watching the History Network, bowl of ice cream balanced precariously on his belly.

“Breaking Bad’s” maneuvers are a bit different. When Walter Bic’d his head in Season 1, it was regarded as a breach of his established character as a dopey, aww-shucks high school science teacher. Like most of the character’s odd behavior, it was chalked up to his cancer diagnosis, attributable to a compounded midlife crisis. Walter White exploits these assumptions, as far as he could, as a way of masking his criminal double-life. But for Walter, self-imposed baldness means control. It means taking control.

It’s easy to accuse “Breaking Bad” of pop nihilism, abusing the who-gives-a-shit attitude of its various everymen (and women) who are ignited by standing outside the law, enlivened by extortion, and murder. But what the show really trades in is pop fatalism, an assertive ethic of owning and accounting for actions and decisions made in the face of overwhelmingly bleak outcomes, no matter how destructive, no matter how facile.

Walt’s ritual shaving is one of his highly deliberate decisions that, for better or worse, he sees through to the end. It’s telling that when we’re reintroduced to Walter White in the flash-forward opener of the fifth season premiere, he appears to have returned to the state in which he was first introduced — cowed, browbeaten and topped with a scuzzy pelt of dusty brown hair.

“Breaking Bad’s” swelling ranks of hairless archetypes are bald not in the way that George Costanza — or his even barer update, “Curb Your Enthusiasm’s” Larry David, who continually tries (and fails) to make baldness a form of identity politics — is bald, but bald in the way that Bruce Willis or Yul Brynner or Vladimir Nabokov is bald. Not enfeebled or emasculated, but sleek and effectual. Bald like a clenched fist or one of those bowling ball-shaped cartoon bombs is bald. Bald like a bullet is bald. Baldness has become more than a character tic or wardrobe choice, it’s become a guiding ethos, the marker of the show’s pop fatalism.

Breaking Bad’s fairly straightforward moral paradigm — everyone’s corrupt, or at least corruptible — uses baldness as its benchmark. When Jonathan Bank’s Mike was introduced in the second season, working as a man-at-hand for the unscrupulous Saul Goodman, the passing physical resemblance between him and Walter was immediately apparen, cue ball do, goatee and all. As his history as a former beat cop turned criminal enforcer for a major drug lord was revealed, he served as something of a cautionary tale. Walter could become Mike: callous, ethically detached, emptied of emotion safe for the occasional biting wisecrack.

Last season, Aaron Paul’s Jesse, consumed by the guilt of his whole-hog transition from petty thug to hardened killer, shaves his head during an extended drug binge (the actor’s idea, apparently), ushering himself into the show’s larger clean-shaven schema. Like Walter before him, Jesse hatches from the cocoon of immorality slightly diminished, but with that invigorating feeling of control and self-determination. Or the illusion of it, anyway. Jesse is to Walter as Walter is to Mike with Hank — himself a less-than-noble hero who has little problem stepping outside of his limited authority, acting on hunches and violent impulse — orbiting in the periphery. If everyone’s bald, then no one is. It’s become a way of complicating and entangling the characters’ complex motivations and fidelities. Loyalty and morality are all just shades of bald.

There’s a sense that this baldness aesthetic, like the cloudy green exhales of methamphetamine chuff that define the show’s color palette, exists at the program’s formal level, too. Like its hairless antiheroes, “Breaking Bad” is itself a bald show — resourceful and pleasingly unadorned. Superficially, the program has distinguished itself indulging various attempts at formal intervention. There’s the sun-drenched time-lapse photography, the “Hey, let’s shoot from … over there!” approach to camera placement and oddball angles, and those breathlessly baiting cold opens. If it’s not the best-directed show on television, it’s certainly the most-directed. (Vince Gilligan just netted his second Emmy nomination for directing. And sure. Why not?) It’s just set dressing, though, flashy embellishment that suggests rather than defines character — like Heisenberg’s trademark pork pie hat.

“Breaking Bad’s” great strength is how bluntly efficient it is. Its intrigue may not be as multifarious as “Game of Thrones,'” nor its atmospherics as densely layered as AMC’s other flagship series, “Mad Men.” But each episode of “Breaking Bad” (each great episode, anyway) functions as an object exercise in crackerjack plotting, a perfectly gripping use of its 47-or-so minutes.

It’s like cracking open a Swiss watch and watching it tick, the gears of character, pacing and carefully deployed violence whirring in tune. Its apparent complexity belies a more harmonious simplicity: the intoxicating thrust of a serialized drama brusquely stampeding forward, head down, like a marching Lee Marvin hero or a runaway train in a Tony Scott movie.

It’s here that “Breaking Bad’s” essential baldness, its status as the baldest show on TV, bares itself. Baldness is not just “Breaking Bad’s” style. It’s its mode. Its mandate. This is cold, deceptively unvarnished television, stripped right down to the wood. We’ve come a long way from the male pattern baldness hysteria of ‘90s sitcoms. But hucksters hocking hair plugs and growth tonics probably needn’t worry. There’s plenty of money to be made in razors too.