Once, when I was nine years old, my older sister—then 15—invited me to her room. This in itself was an honor and a privilege, but today there was something even better: Kira was about to embark on a disciplined but rewarding diet of fat-free foods, and she wanted to know if I would join her. We would be partners! We would support each other, encourage each other, lose weight together! There would be challenges, of course, but together, we would succeed.

The first step, Kira explained, was to eliminate existing temptations, such as the great stock of Halloween candy currently occupying a corner of my bedroom closet. It wouldn’t do to try to ignore it, or to save a small selection for later, or even to enjoy one final fun-size Milky Way. The candy must go.

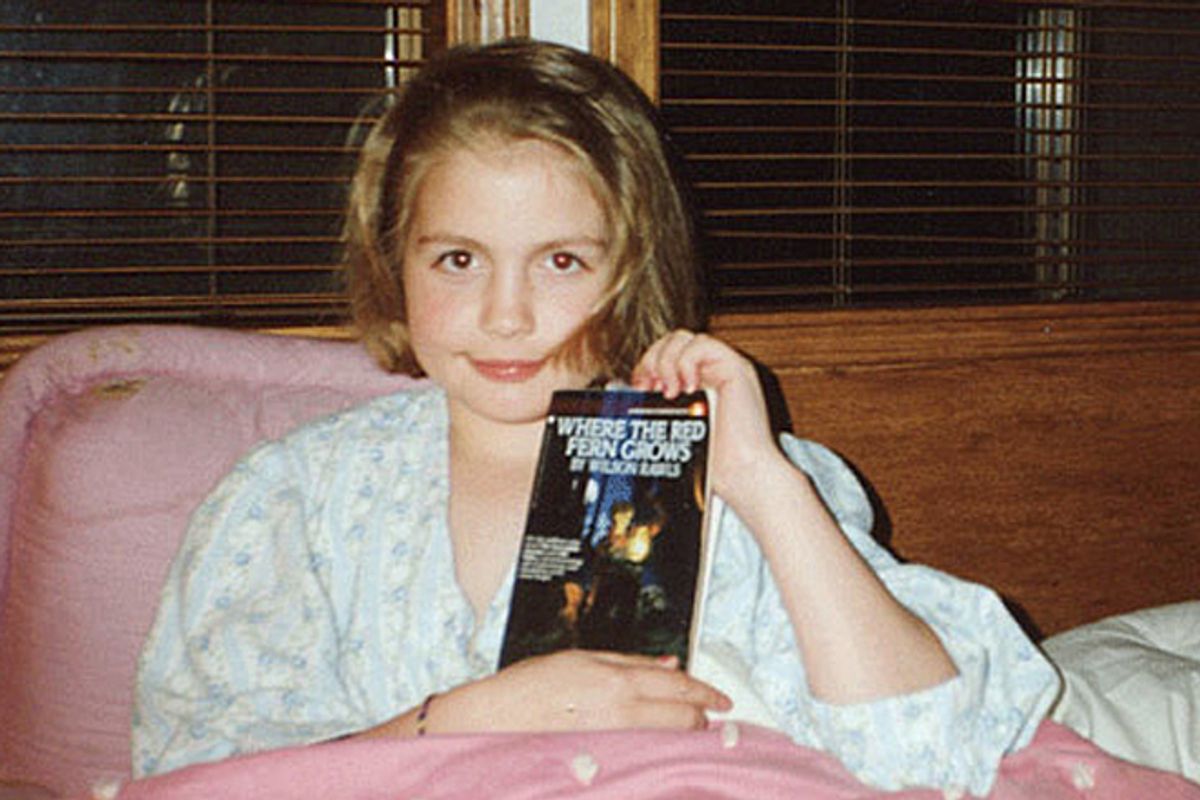

I complied without hesitation. I did not pause to consider the fact that this was by far the largest supply of treats I had ever amassed. I did not linger on the memory of shuffling through the streets of suburban Portland for hours, dressed as a housewife in slippers and robe, in the rain. I did not immediately recall growing steadily colder and more miserable as I followed my brother Gabe from door to door in his relentless and dogged pursuit of a full pillowcase, or the descent into hypothermia, or lying in bed later that night, shivering uncontrollably while my mother buried me under a heap of blankets.

I didn’t think of any of that. I toted my stash to the garage, breathed in the sweet confusion of all its artificial scents one last time, and emptied my pillowcase into the trash.

In family lore, that day is remembered as “the time Gabe got caught digging through the garbage for Emily’s candy,” but in my personal history, it also marked the beginning of a long and inglorious legacy of dieting. I’m embarrassed enough of this history that I might actually have managed to forget it, except that much of it is written down in a diary I somehow still have.

The diary begins in seventh grade, two years after my first adventure in dieting. In one entry from that year, I “make a pact with myself” to lose 15 pounds in three weeks. A few days later, I confess that I need some motivation to help shed the pounds and hope that being around my best friend will help: We were carrying eachother (sic) around on our backs and she is so much lighter than me! I felt so bad and fat and slobby maybe I’ll be able to stay away from everything that tastes good now.

Of course, like most people, I always really liked everything that tastes good. Once, around first grade, I spent the night at my friend Kathleen’s house and woke to the smell of bacon. When I sat down at the kitchen table, Kathleen’s mom put a full plate of glistening, curling red-gold strips in front of me. Soon, Kathleen’s older sister came in and asked, “Where’s the bacon?” The mom looked from the empty plate to me to her daughter, who said, “She ate all the bacon?”

I was not, in other words, a naturally talented dieter. But after a few dozen false starts in the middle school years, I discovered a trick that made it easy to stay away from everything that tastes good. All I had to do was remember four words:

Food is the Enemy.

As an adult who hopes to someday raise children of my own, the fact that I learned this trick from my mom—who is an extraordinary human being and an amazing mother—terrifies me. She had not intended to instill in me a fear, animosity, and distrust of food. She told me, in her characteristically open and honest way, about her own struggle with anorexia—how refusing to eat had been a prolonged act of teenage defiance and rebellion; how it had given her the feeling of agency and the illusion of control.

It was meant as a cautionary tale, but when, just before the end of middle school, my family uprooted from Portland and drove across the country to a new house in a strange neighborhood in the alien town of Pittsburgh, when the world started to spin, agency and control became the things I wanted most. So I took my mom’s stories, learned this phrase—which was her weapon—and used them to start my own war on food.

Food is the Enemy.

Teaching myself to believe that food was the enemy was a simple matter of making the connection between the fat on me and the fat in my food. I thought about my bodily fat while I ate and, when I saw overweight people, I stared at them and tried to imagine the big pile of the food their fat came from.

The strategy was amazingly effective, and victory was, if not sweet, rewardingly slimming. I dropped 20 pounds in just a couple of months. My diet was atrocious by nutritional standards—Rold Gold pretzels and Diet Coke were its two staples—but I never became dangerously thin. I had been a little flabby before, and now I was a little skinny.

Meanwhile, in my mind, nothing changed—I continued to obsess over my weight, only now with the added pressure of starting to recognize that I wasn’t really being rational. In one diary entry from tenth grade, I respond to the fixation recorded over the previous pages: It makes me sick that I’ve been thinking and talking about going on diets for years...I hope it’s an adolescent thing and that I don’t have a problem...I don’t think I’m anorexic—you’d have to be out of your mind to think I’m anorexic—but I do think I’m overweight. I try to tell myself that I’m the normal weight and everything and stop thinking about it, but it’s hard.

Part of what made it hard was that there was always a new diet to try, and my mom was usually already trying it. She was always quite thin, but she explained her adherence to each new formula by saying she was looking for a better, healthier, more energizing way to eat (and, occasionally, she would admit, “I guess you never quite get over it”). My mom never tried to talk me into any of these diets, but they were always there waiting for me—the books hanging out on our kitchen table with an air of enchanting promise, like a new drug.

The Atkins diet was a mainstay. There was also, in somewhat chronological and increasingly bizarre order: the Atkins induction diet (more descriptively known as the cream-cheese-and-macadamia-nut diet), the St. Joseph’s Hospital diet, the Eat Right for Your Blood Type diet, the Fat Flush cleanse, and the arguably sub-paradisal Shangri-La diet.

There was always a new diet to try, and my mom was usually already trying it.

Somewhere within this nutritional gauntlet, my fervor for dieting in general began to falter. I wanted to be thin, but that didn’t make it any easier to swallow splinters of psyllium husks floating in unsweetened cranberry juice, or to belly up to the kitchen pantry several times a day for shots of extra-light virgin olive oil. I was still at war with food, but somehow, eating joyless, bun-less cheeseburgers slathered in mayonnaise never made me feel like I was winning.

After my sophomore year of college, I moved into a co-op on the far end of campus and was, for the first time, effectively cut off from the world of dieting. The house’s supply of General Unspecified Free Food (or GUFF) was dictated by the voice of the People, and the People said yes to mammoth blocks of cheddar cheese, plastic tubs filled with a thick red slurry that passed for salsa, bags of frozen chick patties. At one of my first co-op meetings, there was a vigorous debate over the People’s stance on skim milk; I gathered then that the communal budget would not bend for Skinny Cow ice cream sandwiches or Olean fat-free potato chips. The People said no to diet foods.

In fact, my fellow co-opers seemed to treat the whole weight-loss enterprise as a cause for shame. Though I didn’t really understand the details, I gathered from them that dieting was tied up with the other unpleasant parts of mainstream society: crass consumerism, soul-deadening materialism, the subjection of women.

Still, my dieting habit would not be broken by leftist ideals. I kept my non-GUFF diet foods hidden in the back of the fridge and waited for the coast to clear before sneaking my scale to and from the bathroom down the hall. I could be shamed out of dieting in broad daylight, but I could not be shamed out of dieting altogether.

I could, however, be inspired out of it.

I could not be shamed out of dieting altogether. I could, however, be inspired out of it.

Abra and I became friends near the end of college, during a six-week academic program that was, at its core, a long meditation on the phrase, from Walden: “I went to the woods because I wished to live deliberately.” For most of us, that meant thinking and talking and reading about living deliberately. For Abra, it meant baking bread.

At first, I thought of Abra as someone who just liked to cook. It was an honest mistake—I hadn’t met anyone like her before—but as I got to know her, I realized that her passion for food ran much deeper than that. The first time she tried to explain it to me, we were sitting on some big rocks at camp, swatting mosquitoes and looking out over the lake. She recalled a scene in Toni Morrison’s Beloved in which Sethe is standing at the stove, making biscuits, while her lover stands behind her, holding the weight of her breasts in his hands. I hadn’t read Beloved and didn’t fully grasp the meaning of this passage, but I understood that, for Abra, it captured something essential about food, about the grace and importance of nourishment and the hardship and joys of providing it. I didn’t need to understand her perfectly to realize that Abra’s view of food was more nuanced—and beautiful—than any I had encountered before. My own carefully cultivated relationship with food, my war, began to feel shallow, misguided, and sorely uncultured.

I can’t say that my thinking changed all at once, there on the rock above Lake Sebago, but my peace with food probably become inevitable through my friendship with Abra. When she talked about food, about cheeses and pork shoulders and duck liver and Coca-Cola Classic, I hung on her words, secretly anxious to fold her views into my own.

One night, a few months after we returned home, she invited me over for a fried egg sandwich. I’d like to say that I can’t really account for the apprehension I felt over this event, but the fact is I had never eaten a fried egg sandwich before, and I’d always thought of them as being...just a lot of bread and fat. It was dismaying to watch as she cut thick slices from the loaf of bread, and then even more so when she layered pastrami on top. I listened to the egg sizzle in butter—plenty of butter—and began silently planning my next workout. But then Abra took her sandwich with both hands and bit in unabashedly, and I took courage in how beautiful she was. “Ok, I guess I can do this,” I thought. It was delicious.

Eventually, of course, we saw each other less and less frequently, living different lives in different states. Each visit is still a gift. Whenever we see each other, I find myself eating meat that falls off the bone, something tender and exquisite, something that speaks to the richness of our lives. But when she's not there, when I catch myself in front of the diet ice cream freezer at the grocery store, or when I wince a little at the thickness of the square of butter I drop into a pan, it's her voice I hear, saying, "You need the fat, because fat is what carries the flavor." That voice is what lets me think back to the little-girl me, the one who just ate all the bacon, and now know that she was right all along.

Shares