I’ve decided to go off my meds. If you knew me, you’d probably say I was crazy for even contemplating such a move — crazy as in: "Holy crap! She’s-off-her-meds" crazy. My friends think so, and so does most of my family. Because it took seven years to stabilize my last “episode” of bipolar disorder — the increasingly severe cycling that started when I hit 39 and my hormones began to fluctuate — a normal phenomenon for women that age but one my bipolar brain could not tolerate. But very little is known about the effects of hormones on bipolar disorder so what followed were seven horrific years of deep depressions and horrible irritable, anxiety-ridden manias (I never got the giddy, top-of-the-world kind you see in the movies).

During those seven years, I tried innumerable treatments, but I also wrote my first novel. It was raw and dark; the life I was living when I wrote it is splattered on every page. I’m not sure that I need to be that sick in order to write — as least, I certainly hope not. And a year and a half after discovering the magic bullet that finally made me well — a little fire engine red pill that was supposed to be a long shot with a 17 percent chance of success — I am stable. Well. So well in fact that I can’t write a word. Some days I am more, most days, though, I am less. Not less stable, but less productive, less creative and less able to feel or remember much of anything. I have stabilized into a kind of reluctant, anhedonic numbness. I have no sense memory of the things I used to feel. Which is a problem because I’ve been asked to write about those seven years. About what it was like — for real.

But my memory of those years — the period of time during which that story, my story, occurs — is cloudy at best. Possibly it’s a result of the little red pill and the many other drugs I’m taking to treat my bipolar disorder, or perhaps it’s a result of the toll seven years of nonstop, treatment-resistant ultra-rapid cycling and manic and depressive episodes have taken on my now fried gray matter. Either way, my memory is shot.

My memory is not, of course, entirely gone. I am not an amnesiac. It is more like a topographic map. The dark contour lines stand out in relief as single events or periods of time I remember in (sometimes excruciatingly) vivid detail. And my memories of the distant past — mostly seminal traumatic experiences, like my father’s suicide, rise up like vertiginous mountain ranges. There are also, however, vast expanses of low-lying flatlands — months and even years of unending emotional and psychological chaos that just bleed together.

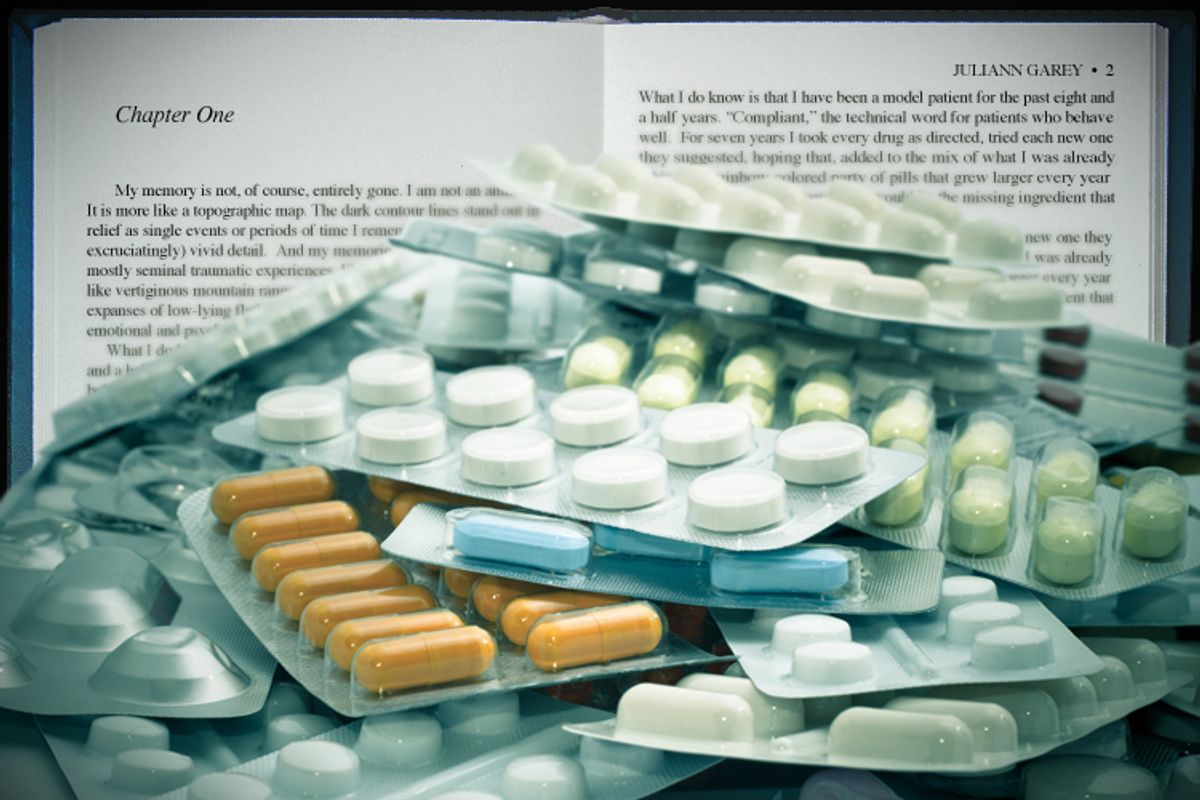

What I do know is that I have been a model patient for the past eight and a half years. “Compliant,” the technical word for patients who behave well. For seven years I took every drug as directed, tried each new one they suggested, hoping that, added to the mix of what I was already taking — a rainbow-colored party of pills that grew larger every year even as I seemed to get worse — it would be the missing ingredient that made the whole cocktail work.

And I gamely participated in the experiments. Among them: a drug for prostate cancer that was supposed to have mood-stabilizing effects but unfortunately induced psychosis; birth control pills intended to balance hormones, which instead caused protracted bleeding and violent mood swings; a trial of clozapine, an anti-psychotic with a “black box warning” so dire patients who take it must be registered with the government; self-administered daily injections of Lupron, a highly toxic fertility drug that induced artificial menopause virtually overnight, the side-effects of which included a six-week-long migraine and temporary paralysis.

There were many, many, many more. And I’ve kept almost all of them — the failed treatments — neatly labeled in Ziploc bags marked “antidepressants,” “anti-convulsants,” “anti-psychotics,” “anti-anxiety,” “other,” and finally “hormonal interventions,” which fill two bulky bags crammed with gels, patches and various kinds of birth control pills. Altogether they fill an enormous Duane Reade shopping bag.

I realize I could have simply kept a running list of tried and failed drug treatments, but I suppose I wanted the physical proof that a list alone could not provide. A list of drug names, no matter how long, lacked the weight and substance of my Duane Reade shopping bag. And maybe I hoped that seeing that bag up close and personal might make the next new doctor take an extra moment or two before insisting we give one of the drugs in my bag just “one more try” because “your brain is always changing.”

I keep the drugs I now take every day in a stretchy blue sack with a big red zipper that my daughter sewed for me in art class when she was in third grade. It even has my initials on it. Normally when I go to my psychopharmacologist I just tell her which drugs need refilling. But after a year of complaining about my current state of affairs — a year during which all my doctors have been too afraid to rock the pharmacological boat — I put my foot down. This last time I took the blue sack with me. It’s not nearly as big as the one from Duane Reade but still pretty hefty — too large to fit in any regular pocketbook or backpack. I lined all the bottles up on her desk like I do at home twice a day when I take them. And she finally got it. “It’s too much,” she said. “We can do better.”

I am lucky my doctor understands that I need to set the bar a bit higher than functional stability. And so this off-the-meds craziness is at least medically sanctioned. But I have been warned that the road to recovering my memory will likely be a rocky one. There will be potholes and blind curves and things will have to get worse before they get better. All I can hope is that at some point during the ride I will find myself with something to write about and that when that happens I will know it.

Shares