My first problem with Ellen Cushing's eloquent rendition of a now-classic theme -- how the Internet economy is screwing up everything that was great and wonderful about San Francisco -- came with the headline: "The Bacon-Wrapped Economy: Tech has brought very young, very rich people to the Bay Area like never before. And the changes to our cultural and economic landscape aren't necessarily for the better."

Specifically, the "like never before" part. Say what?! How quickly people forget! This exact phenomenon played out just over a decade ago! The dot-com boom sucked in a massive influx of young people who walked straight out of college (or skipped it altogether) and into cushy jobs at a vast horde of absurd and ludicrous start-ups. The Ferrari dealership in Los Gatos lived off of callow young men cashing in their first batch of stock options.

And oh lord, there was much hand-wringing and gnashing of teeth and breast-beating about cultural decline. Salon, in fact, was responsible for publishing one of the very first Internet backlash stories of them all, way back in 1999: Paulina Borsook's "How the Internet ruined San Francisco: The dot-com invasion -- call them twerps with 'tude -- is destroying everything that made San Francisco weird and wonderful."

At the time, Borsook's story was one of the most popular pieces Salon ever published. And believe me, the irony of one of the first Web magazines -- which was desperately attempting to grab as much advertising from ludicrous and absurd Bay Area start-ups as it possibly could-- slagging the entire Internet economy was lost on no one.

Then came the dot-com bust, and all those young people lost their jobs. They were very upset. In the ensuing months I think every single one of them wrote me an email asking for the opportunity to explain to Salon's readers how they'd learned that capitalism was really mean and unfair. (I edited Salon's technology and business sections at the time.) San Francisco and the rest of the Bay Area, meanwhile, struggled through a recession. (And recessions, by the way, suck. You lose your healthcare, your favorite restaurant closes, you can't get a job. Call me crass, but I prefer booms.)

So now we're doing it all over again. There's a new tech bubble in town and San Francisco is getting ruined again. But this bubble too will pop, and the young millionaires that Cushing describes as having "no understanding of risk" will get their first meaningful introduction into the ups and downs of the business cycle. And a bunch more restaurants will close.

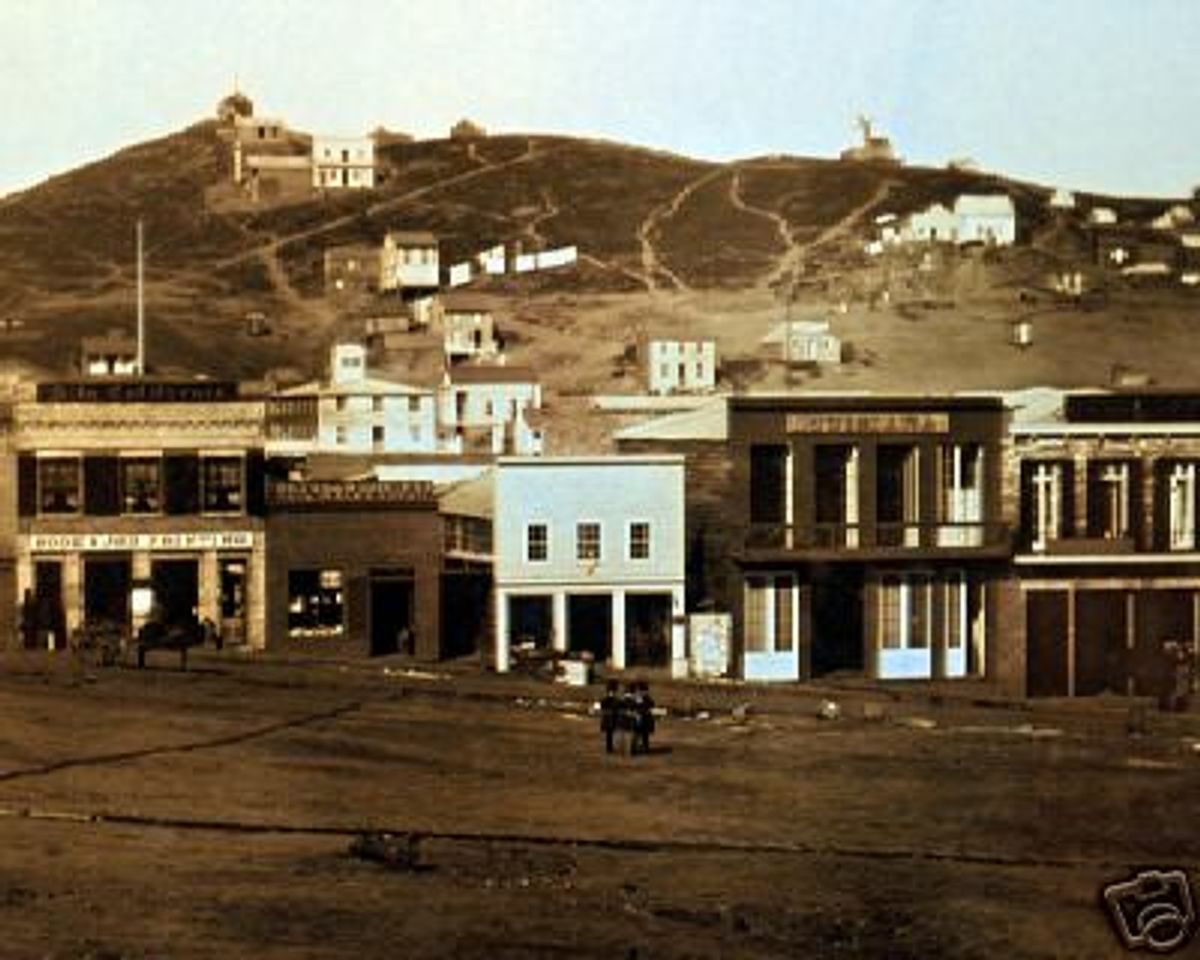

It's possible, I guess, that the current bubble is ruining San Francisco even more than the dot-com boom, or at the least simply continuing a long decline from some long-lost golden age. The moment we hit "send" on our first email in the mid-'90s was the moment our culture started an irretrievable slide into decay! Oops! But I always think it's worth taking the long view when evaluating Bay Area cultural vibrancy. Never forget: San Francisco was founded on get-quick-rich greed, on the lust of boorish 49ers whose sense of culture extended no further than the length of their pick-axes. An influx of barbarians looking to score easy money and then wasting what they stumbled into on liquor and whores (or $25 bacon-wrapped fried chicken sandwiches) is as essential to the essence of this region as our supposedly awesome cultural life -- whether that be the "weird and wonderful" subcultures that Borsook worried about, or the high European edifices that Cushing sees crumbling into dust.

That's not to say there isn't a solid point in Cushing's argument. The new rich seem to have different priorities than the old rich. They'd rather put their money into Kickstarter to fund a "Veronica Mars" movie or string fancy lights on the Bay Bridge than help the symphony or ballet make it through another season. If current trends continue, the old titans may well be in trouble. Mozart, Verdi, Tchaikovsky -- you guys had a good run, but we've got Twitter now. See you later!

That would be sad. But it's dangerous to generalize from the behavior of a bunch of 20-somethings to permanent changes in the zeitgeist. The thing about young people is -- they grow up. Their priorities change. They might ultimately decide that keeping Beethoven alive is more important than getting another season of "Arrested Development" made. Or having made their money, they might go into politics. A lot of them are due to get burned in the next recession, and their scars will make them wiser. As they lick their wounds, San Francisco will ready itself for the next wave.

But the weirdest part of Cushing's article is her thesis that the failure of the new rich to accouter itself in the ostentatious trappings of the old is itself indicative of a decaying social fabric.

But the thing about this particular brand of low-key wealth is that it can lead to a false sense of self, on both a micro and a macro level. Consumption is still consumption even if it's less conspicuous. Class may be harder to see here, but that doesn't make it any less real. Mark Zuckerberg's still a billionaire, even if he's wearing a hoodie and jeans. And if you don't feel or look rich, you don't necessarily feel the same sense of obligation that a traditional rich person does or should: Noblesse oblige is, after all, dependent on a classical idea of who is and is not the nobility. As that starts to fall away, obligation — to culture, to the future, to each other — begins to disappear, too.

I've read a lot of criticisms about the culture of Silicon Valley in my day -- heck, I've made plenty of them myself -- but the notion that the new rich kids of Twitter and Facebook represent the decline of civilization because of their failure to exhibit the proper "noblesse oblige" is the most anti-democratic, elitist, un-American critique of the Internet economy I have ever seen. Cushing mocks the priorities of the Kickstarter crowd, but to me, there's something a lot more liberating and culturally vibrant about a bunch of people individually donating small sums to make someone else's dream come true than there is about the sight of Mark Zuckerberg writing a check for a million dollars to the San Francisco Opera so that "La Traviata" gets another run.

Decline and fall by hoodie? I'm sure the gold miners of the 19th century would have had a good laugh at that.

Shares