Any serious talk of pragmatism and compromise in American politics usually ends with some nettlesome questions: What about the social issues? What about abortion? What about gun control? These are issues on which reasonable people disagree passionately. Anyone who tells you that there is a “right” answer on abortion has not spent much time thinking about the issue or lacks the empathy to appreciate how other people think about it. Americans’ views on these issues tend to be theological — literally in many cases. No amount of arguing or data gathering is going to change anyone’s core values; we’ve dug our intellectual trenches and hunkered down.

So how can a party built around the idea of pragmatism and compromise deal with issues whose defining feature is a deep and conflicting vision of what is right and wrong?

With pragmatism and compromise. Here is the fundamental insight: Reasonable people disagree about whether or not abortion should be illegal; but no reasonable person thinks that abortion is a good thing.

Reasonable people disagree about how readily guns should be available and what the requirements for purchase ought to be; but no reasonable person wants guns to fall into the hands of criminals or those who are dangerously mentally ill.

There are plenty of other social issues: drug policy, stem cell research, flag burning, the death penalty, and so on. In time, the Centrist Party will have to wrestle with them all. For now, abortion and guns will do a fine job of illustrating how the Centrist Party can bring people together on issues that normally drive them apart. The key to diffusing these ideologically charged social issues is refocusing them on two more pragmatic questions: 1) What is the real harm to society associated with this activity? 2) How can we minimize that harm? The answers to those questions will dictate Centrist policy. Is that going to make everybody happy? Of course not. But the purpose of the Centrist Party is not to make everybody happy, particularly the political poles. The purpose of the Centrist Party is to craft an agenda that a large swathe of underrepresented moderate American voters can get behind. On the major social issues, that’s entirely possible.

Let me pause to note that there is one prominent issue missing from that introduction: gay marriage. The Centrist Party must support gay marriage for the simple reason that there is no legitimate reason to be against it. What is the potential harm to society associated with same-sex marriage? Answer: There is none. Marriage is a private contract between two consenting adults. It is the capstone to a loving relationship that also bestows significant legal rights. There must be some compelling harm that spills over to the rest of society if government is to stand in the way of this private behavior. But there is not. How might it be bad for society in general if two people of the same sex decide to enter into a legal relationship? As a former military officer once grumbled to me, “I don’t have to like it. I just don’t think it’s any of my business.” The notion that gay marriage somehow diminishes heterosexual marriage would be laugh-out-loud funny if it were not the most common rationalization for denying gay couples a basic right.

This is a position, by the way, that both liberals and small-government conservatives ought to agree on. Gay marriage promotes social justice (a traditional liberal objective) by granting new rights to a group that has historically been discriminated against. It also gets government out of the business of arbitrating private morality (a traditional conservative objective). Obviously there is a significant clash on this issue between traditional conservatives, who favor small government with a limited reach, and social conservatives, who are eager to have government police private behavior. This is only one of many areas in which the core constituencies of the Republican Party are fundamentally at odds with one another.

For the Centrists, there is no need to compromise on this issue because there is no intellectually legitimate difference of opinion. As an aside, supporting gay marriage is also good politics in the long run. A Gallup poll conducted in 2011 found that for the first time a majority of Americans support gay marriage (53 percent), up from only 27 percent in 1996. In 20 years, this won’t be a mainstream issue. In a private conversation, a senior Gallup official said that he has never seen a social issue on which opinions have changed so quickly. Not only are attitudes changing fast, but young Americans are far more likely to support gay marriage than older Americans. The same Gallup poll found that 70 percent of 18 to 34 year olds support gay marriage, compared to only 39 percent of those 55 and older. Young people will get older; old people will die. Even if no single American changes his or her mind on this issue, the passage of time alone will lead to a steady change in overall public opinion, assuming young generations continue to be more comfortable with homosexuality than older generations.

Gay marriage is an anomaly among social issues in that the argument is so intellectually lopsided. Abortion and gun control, along with most social issues, involve legitimate ideological differences that are irreconcilable. Both sides have defensible views (as much as their opponents would like to pretend otherwise). Still, there is a political path forward.

Abortion

Let’s start with abortion. Anyone who has been in America for longer than six months is familiar with the competing narratives. If one believes that life begins at conception, then every abortion stops a beating heart. For those who view abortion as akin to murder, society has an obligation to protect the innocent unborn. The belief that life begins at conception is entirely defensible, and if one believes that, then of course abortion ought to be illegal — for the same reason that it is illegal to kill a two-year-old.

The obvious countervailing view is that society has no right to tell a woman what to do with her body. A developing fetus is inextricably linked to the woman carrying it; government ought not compel her to carry and deliver a baby against her will. If one believes that the rights of a pregnant woman trump those of her unborn baby, then abortion should be legal. This, too, is a defensible position.

And so, the issue is seemingly irreconcilable, with roughly half of Americans describing themselves as pro-choice and about the same proportion describing themselves as pro-life. Abortion is the epitome of political trench warfare. America’s abortion policies have not changed fundamentally since the Supreme Court decided the Roe v. Wade case, yet we fight skirmish after skirmish on the margins (waiting periods, mandatory vaginal ultrasounds, etc.). The most serious problem for the country is that the abortion issue contaminates every other facet of politics and governance: every election, every judicial appointment, every discussion around public funding for women’s health. The philosophical disagreements over abortion policy may be defensible, but the degree to which that single issue paralyzes the nation on other issues is not. We need to move forward.

The pragmatic way to move forward is to seize on two areas around this contentious issue where most Americans are more likely to agree than disagree.

First, most Americans are more ambivalent in their views about abortion than the polls might first suggest. Once one moves away from the political extremes, the chasm between pro-choice and pro-life grows more ambiguous. Two thought exercises will help illuminate this point.

Thought exercise number 1: If you are pro-life, then presumably you believe that a fetus deserves government protection. According to this worldview, a developing fetus is a person, and killing a person is not a “choice.” Okay, fair enough.

Yet, if you are pro-life, there is a good chance that you also believe that exceptions ought to be made in the cases of rape and incest. According to Gallup, only a small minority of Americans believe that abortion should be illegal in all circumstances; rape and incest are typically offered as exceptions.

The curious thing about this seemingly reasonable position is that it has a fundamental inconsistency. Would you allow a woman to terminate the life of a two-year-old who was born of rape or incest? Probably not. If a fetus deserves the same protection as a two-year-old, why does the source of conception make any difference at all? It doesn’t. Instead, the Americans who believe that abortion should be illegal except for cases of rape and incest are really thinking about the mother; a woman should not be forced to carry a baby against her will in some circumstances. There is a glimmer of pro-choice thinking there, and that ought to give us some hope for building a Centrist consensus on this issue.

Now for thought exercise number 2: If you are pro-choice, here are some questions for you. Does it make you uncomfortable if a woman uses abortion as a form of birth control? Does it make you uncomfortable when families in China and India use abortion to select the sex of their child? Do you feel less comfortable with legal abortion in the second or third trimester than in the first? Would you support a woman who decided to abort a fetus with brown eyes because she preferred a blue-eyed baby (or some other genetic endowment)? If you answered yes to some or all of these questions, then you resemble many Americans who describe themselves as pro-choice. Again according to Gallup, only a fifth of Americans believe abortion should be legal in all circumstances.

And no one is pro-abortion. Very few pro-choice Americans really believe that having an abortion is the moral equivalent of having an appendix removed. A high proportion of pro-choice voters would defend a woman’s right to terminate a pregnancy while still describing every abortion as a mistake, a tragedy, or both.

Building on all of this, the Centrist Party can cobble together a consensus around a policy that advocates for the following: 1) Safe and legal access to abortion (and widespread availability of products caught up in the abortion debate, such as the “morning-after pill”). 2) A concerted effort to reduce the number of abortions, including greater access to contraceptives, comprehensive sex education, and a better social safety net for poor women. (One of the most common stated reasons for getting an abortion is a financial inability to have and raise the child.) 3) Placement of some limits on abortion services, provided that they are not designed exclusively to curtail access to abortion or to humiliate women. If, for example, evidence suggests that a significant number of women choose not to have an abortion when some mandatory waiting period is put in place — a genuine change of heart — then it would be perfectly reasonable to mandate such a waiting period. This is consistent with the goal of providing safe access to abortion while also minimizing the number of abortions. However, if evidence suggests that the effect of a waiting period is merely to erect a barrier to a legal medical procedure, particularly for low-income women, then there is no place for it.

This kind of non-absolutist policy is consistent with what most Americans say they want. Most important, this is a policy around which a wide swath of moderate voters can rally, particularly the growing number of young voters who describe themselves as “fiscally conservative and socially liberal.” We can get beyond the trench warfare of abortion politics, for a number of reasons. First, the Centrist policy outlined here is largely consistent with the status quo. Centrist candidates would not be crusading to make radical changes on this issue; they can spend their time and effort focusing on the many important American challenges beyond abortion.

Second, the Centrist Party will acknowledge the legitimacy of the pro-life viewpoint and seek to deliver what those Americans ostensibly care most about: fewer abortions. To do that, we will have to get past many of the most counterproductive policies of the pro-life movement. We should not pretend that abstinence education is sufficient to prevent unwanted pregnancies among teens. Both common sense and extensive research suggest that abstinence education alone does not work.

We should not cut off government funding for women’s health centers that provide abortion services. These clinics typically provide other important health services, including ones that are crucial to preventing unwanted pregnancies, such as access to contraceptives. Meanwhile, we should provide access to contraception and sex education in the United States and around the world. (Most abortions take place in the developing world.)

Finally, the Centrist position on abortion is pragmatic. Social conservatives are fighting a symbolic but losing battle. Abortion is never going to be illegal in most of America; focusing on that objective is a fool’s errand. Let’s think about what it would take to outlaw abortion. The first step would be overturning the Roe v. Wade decision. A conservative president might appoint a Supreme Court justice willing to do that, and the new justice might find four other votes. However, one of the important pillars of constitutional law is respect for precedent, which makes overturning Roe less likely with each passing year.

Still, it could happen. Overturning Roe would not make abortion illegal, however; it would merely open the door for the states to do so. (Even before the Roe v. Wade decision, there was no federal ban on abortion, and it is profoundly unlikely that Congress would ever pass such a ban.) In a post-Roe world, abortion would still be legal in many states. Abortions would also be performed illegally (and often unsafely) in states that criminalized the procedure. All of which brings us to the most salient fact underlying the Centrist position on this issue: the abortion rate is shockingly invariant to whether abortion is legal or not. According to a study in the British medical journal Lancet, countries with restrictive abortion laws do not have lower rates of abortion. Western Europe, where abortion is legal and widely available, has an abortion rate that is 43 percent lower than the rate in the United States.

Contemplate this: Has the United States ever convened a serious, high-profile nonpartisan commission, with representation from across the abortion ideological spectrum, to recommend policies that would bring the abortion rate down, apart from making the procedure illegal? No, because we cannot get past the legality debate, even though it is essentially symbolic at this point. The pro-life movement has been consumed with making noise rather than making a difference. As a result, we have roughly twice the abortion rate of countries that have taken a more pragmatic approach. That is a tragedy with no political winner.

So let’s summarize what the Centrist Party can offer as an alternative to the current abortion trench warfare: a policy that respects women’s rights, acknowledges the legitimacy of pro-life views, reduces the number of unintended pregnancies, lowers the abortion rate, minimizes government involvement in private medical decisions, and moves abortion politics to the back burner — all without overturning a 40-year-old Supreme Court precedent or changing any major federal laws. A very large number of American voters can get behind that policy.

Guns

Americans love their guns. And by “Americans,” I mean both law-abiding citizens using guns for recreation and self-defense and the criminals who use guns to commit 11,500 murders every year. The Centrist approach is straightforward: respect the gun rights of the former while doing everything possible to keep weapons out of the hands of the latter. There is no inherent conflict between those two objectives.

Proponents of gun rights believe they have a constitutional right to bear arms: for hunting, for self-defense, for whatever else strikes them. The Second Amendment may be one of the sloppier pieces of writing done by our Founding Fathers, but the Supreme Court has affirmed and clarified the right to bear arms. We are not taking away America’s guns anytime soon.

Gun control advocates, particularly those who live in and around urban areas, believe that restraints on gun ownership would save lives. Among developed countries, the United States is a uniquely violent place, and guns play a role in making that violence deadly. Every kind of criminal activity, from drug dealing to domestic violence, is made worse when guns are involved.

Let’s give everyone most of what they want. Taking guns out of the hands of gang bangers in Chicago would not impinge in any significant way on the life of someone who likes to hunt deer in Wisconsin, or on someone in Washington, D.C., who wants to keep a gun in the house for self-defense (which is a right that the Supreme Court recently affirmed). We can reduce the number of gun crimes, accommodate a full range of hunting and other gun-related recreational activities, and allow responsible people to own guns in their homes. It just requires a modicum of common sense.

The key to making guns less dangerous is focusing on the mechanism by which guns get into the hands of criminals. Guns are different from drugs such as cocaine and methamphetamine. Guns cannot be manufactured in makeshift labs in the jungle or by high school dropouts in basements and garages. The guns that kill innocent victims on our streets come off a legal assembly line, just like cars and televisions. Most are sold legally at retail stores or gun shows, also like cars and televisions. And then sometime after that, they fall into the hands of thugs and psychopaths who have a vicious disregard for human life. The Centrist strategy has one overriding focus: Intercept the flow of guns moving from the right hands into the wrong hands.

Doing that requires two broad steps. First, the Centrist Party must unequivocally support the rights of law-abiding Americans to own and use guns, including handguns, for recreation and self-defense. This position is consistent with the most recent Supreme Court interpretation of the Second Amendment. It is also a position that is acceptable to most political moderates. (Your decision to keep a gun under your pillow is your business.) Most important, it undercuts the disingenuous (but highly effective) argument of the National Rifle Association (NRA) and other gun zealots that placing any constraints on gun ownership is merely the first step in a plot to ban all guns for all people.

Second, the Centrist Party must demand the same responsibility from gun owners that we expect from anyone else handling a potentially dangerous product. Car owners must register their vehicles. Pharmacists must account for opiates and other addictive drugs in their possession. Defense contractors must ensure that secret technologies do not fall into the hands of hostile governments. The idea that gun owners can buy, sell, and use lethal weapons without any government oversight is delusional.

In fact, let’s put the gun carnage in perspective. Roughly 3,000 Americans died in the terrorist attacks that happened on September 11, 2001. Ever since, we have been expending enormous resources and impinging on the rights of law-abiding citizens to prevent any such attacks in the future. Most of us are okay with the majority of the antiterrorism measures that have been put in place. All the while, every year guns are killing nearly four times as many Americans as the 9/11 attacks did. We should do something about that.

And here is what we should do: Every owner of a gun — from the factory producing firearms to the guy putting a pistol under his pillow at night — must be responsible for every weapon in his or her possession. More specifically, every new gun produced in the United States or imported from abroad must be licensed. When a weapon changes hands legally, from retailer to owner, or from private owner to private owner, the license for that particular weapon must accompany the transaction, just like a car title changes hands at the point of sale. Anyone with a legal weapon will have “title” to it. That title will lay out the history of the weapon — every owner since it came off the assembly line. For weapons already in circulation, there would be some transition period, say six months, during which existing gun owners would be required to license their weapons. After that, owning an unlicensed weapon becomes a crime. Because if law-abiding citizens are going to exercise their constitutional right to bear arms, they have an obligation to society to do it in a safe and responsible way.

Technology has the potential to turn gun licensing from an annoying bureaucratic hurdle into a powerful tool for keeping guns out of the wrong hands (or figuring out how they got there). One possible example: Each licensed weapon could have a “ballistic fingerprint” that is registered with the federal government at the time of manufacture, or when an existing weapon is licensed for the first time. The ballistic fingerprint is the unique mark that a gun barrel imparts on a bullet when fired. (This is the same science that law enforcement has been using for decades to determine if a bullet found at a crime scene was fired from a particular weapon.) A gun’s identifying ballistic pattern is much harder to erase or file away than a serial number. The result is that every legal firearm would be licensed to a specific owner and a have a unique fingerprint. If a licensed gun is lost or stolen, the owner has an obligation to report the loss to law enforcement authorities.

Is this a hassle for gun owners? Of course it is. So is waiting in line at the Department of Motor Vehicles to get a driver’s license. That is the price that comes with owning and operating a product that has the potential, when mishandled, to kill or injure other members of society.

What would we get for that hassle? The “fingerprint and license” system enables us to answer the most important question when a particular gun (or a bullet fired from a particular gun) turns up at a crime scene: Where did this gun come from?

This kind of plan moves beyond the questions that gun control advocates usually ask: Who needs to buy 20 handguns? Or, should we ban semiautomatic weapons? Those are the wrong questions. They are all about constraining the rights of law-abiding citizens. Here is the right question: After you bought 20 handguns, why and how did 18 of them end up in the hands of gang members on the streets of Detroit?

If your gun — one of the 20 handguns you purchased last month — is used in a crime and you have not reported it lost or stolen, then you have some questions to answer. And if your “lost” guns repeatedly turn up in the wrong hands, then perhaps you should spend some time in prison, or on the receiving end of a civil lawsuit.

This policy is no panacea for gun violence. It’s a patch, not a cure. The cure is eliminating the gangs, the domestic violence, the drug trade, and so on. Gun advocates have always been right about that. Nor will licensing and fingerprinting necessarily stop the random mass killings in schools and theaters, because the weapons involved in those massacres are often purchased legally by people who have not yet manifested signs that they are dangerous or mentally ill.

This policy also skirts the contentious issue of concealed weapons. If you have a gun in your home, then it is essentially your business. But when you take that gun to work or to the supermarket, then it becomes everyone’s business. Americans are divided about the right to carry concealed weapons. There is no obvious policy compromise, at least not at the federal level. The Centrist approach to this divisive debate would be to lean on federalism. States can decide their own concealed carry laws, contingent upon those guns being licensed as described earlier. It doesn’t much matter in Massachusetts if people are taking guns to the mall in Texas, provided that those guns are licensed, “fingerprinted,” and don’t somehow end up in the hands of a Boston street gang.

A pragmatic licensing policy would help keep guns out of the hands of violent people (and introduce some accountability when guns do end up in the wrong places). True, there are so many guns already in the wrong hands that criminals will still have access to illicit weapons. But it is disingenuous to argue that we should not keep better track of weapons in the future because we have done such a poor job of keeping track of them in the past. Licensing and fingerprinting would raise the street price of illegal guns, perhaps keeping more of them out of the hands of street punks. When guns do end up in the wrong hands, we would have another tool for figuring out how it happened.

On the political front, any sane gun policy runs square into the logical fallacies of the NRA, which has promulgated the myth that any restriction on gun rights leads to a “slippery slope” in which all gun rights will be whittled away: if we as a society make it harder for gang bangers to buy 20 guns in Missouri, then soon it will be illegal to hunt deer in Wisconsin. This belief violates both common sense and formal logic. At the risk of becoming overly pedantic, there is no such thing as a slippery slope. If you believe that owning a bazooka is a bad thing, but deer hunting with a rifle seems perfectly sensible, then we can vote to ban bazookas without eliminating deer hunting. The political logic of groups like the NRA is that even the most benign and sensible restrictions on gun owners merely empower the anti-gun forces to ask for less benign and less sensible restrictions.

But why? Most Americans have no problem with hunting or keeping guns in the home. The fact is that gun owners can have everything they want in exchange for exercising a modicum of responsibility with a lethal weapon. The NRA stands in the path of that “modicum of responsibility.” The Centrist Party is about wrestling the country away from extremist groups whose views are out of sync with those of most Americans. And behold, the policy I have described is something that most moderate voters could live with. The Centrist gun policy unequivocally supports the rights of law-abiding Americans to have and use guns; it demands responsibility from gun manufacturers, retailers, and owners; and it uses technology to keep weapons out of the wrong hands.

Isn’t that better than what we’ve been doing?

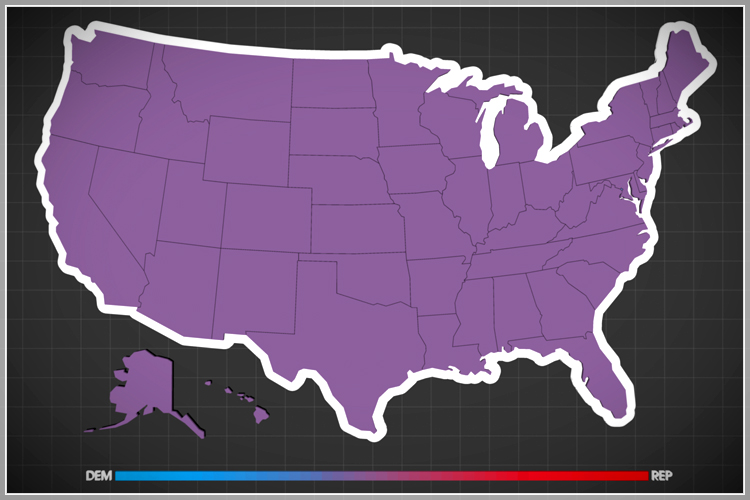

More broadly, isn’t the Centrist approach to social issues a refreshing change to the overheated Democratic and Republican rhetoric? This is an important part of the Centrist Party appeal. On issues like gay marriage and abortion, the Centrists will respect individual rights in ways that are traditionally considered liberal and have therefore been the domain of the Democrats. But this approach to social issues will no longer be tethered to the Democrats’ muddled thinking on economic issues. The result is a combination that describes many moderate voters, particularly young voters: “socially liberal and fiscally conservative.”

The combination of sensible economic policies and a progressive approach to social issues will peel voters away from both parties. From the Republicans, the Centrist Party will dislodge the economic conservatives who have zero interest in the right-wing social agenda but cannot bring themselves to support the Democrats’ populist and undisciplined approach to taxes, regulation, and fiscal policy.

From the Democrats, the Centrist Party will dislodge the voters who respect small government and fiscal responsibility but cannot bring themselves to support the Republicans’ heavy-handed, right-wing social agenda.

Pragmatic moderates will no longer have to tolerate the crazies in their own party because they consider them to be less scary or offensive than the crazies in the other party. Far from being a collection of insolvable stumbling blocks, social issues have the potential to be a defining strength of the Centrist Party.

Reprinted from “The Centrist Manifesto” by Charles Wheelan. Copyright © 2013 by Charles Wheelan. Used with the permission of the publisher, W.W. Norton & Company, Inc.