The writer Jorge Luis Borges once referred to his friend the artist Xul Solar as “one of the most singular events of our era” (from “Xul Solar and His Art,” translated by Christopher Leland Winks, in Xul Solar and Jorge Luis Borges: The Art of Friendship). Those in New York have the opportunity to see an important selection of works by the two friends in an exhibition at the Americas Society. Curated by Gabriela Rangel, the show sheds new light on the work of Borges and, through the lens of friendship, reveals the multifaceted artistic and intellectual project that he and Solar shared. As the quote above demonstrates, Borges regarded the artist as not only a collaborator and interlocutor, but also as a model and inspiration. It alludes as well to the range of Solar’s production. On view are numerous artworks, games, and research inspired by his intellectual curiosity and erudition, plus a large number of watercolors, in which he constructed imaginary universes from many cultures, languages, and artistic tendencies.

The writer Jorge Luis Borges once referred to his friend the artist Xul Solar as “one of the most singular events of our era” (from “Xul Solar and His Art,” translated by Christopher Leland Winks, in Xul Solar and Jorge Luis Borges: The Art of Friendship). Those in New York have the opportunity to see an important selection of works by the two friends in an exhibition at the Americas Society. Curated by Gabriela Rangel, the show sheds new light on the work of Borges and, through the lens of friendship, reveals the multifaceted artistic and intellectual project that he and Solar shared. As the quote above demonstrates, Borges regarded the artist as not only a collaborator and interlocutor, but also as a model and inspiration. It alludes as well to the range of Solar’s production. On view are numerous artworks, games, and research inspired by his intellectual curiosity and erudition, plus a large number of watercolors, in which he constructed imaginary universes from many cultures, languages, and artistic tendencies.

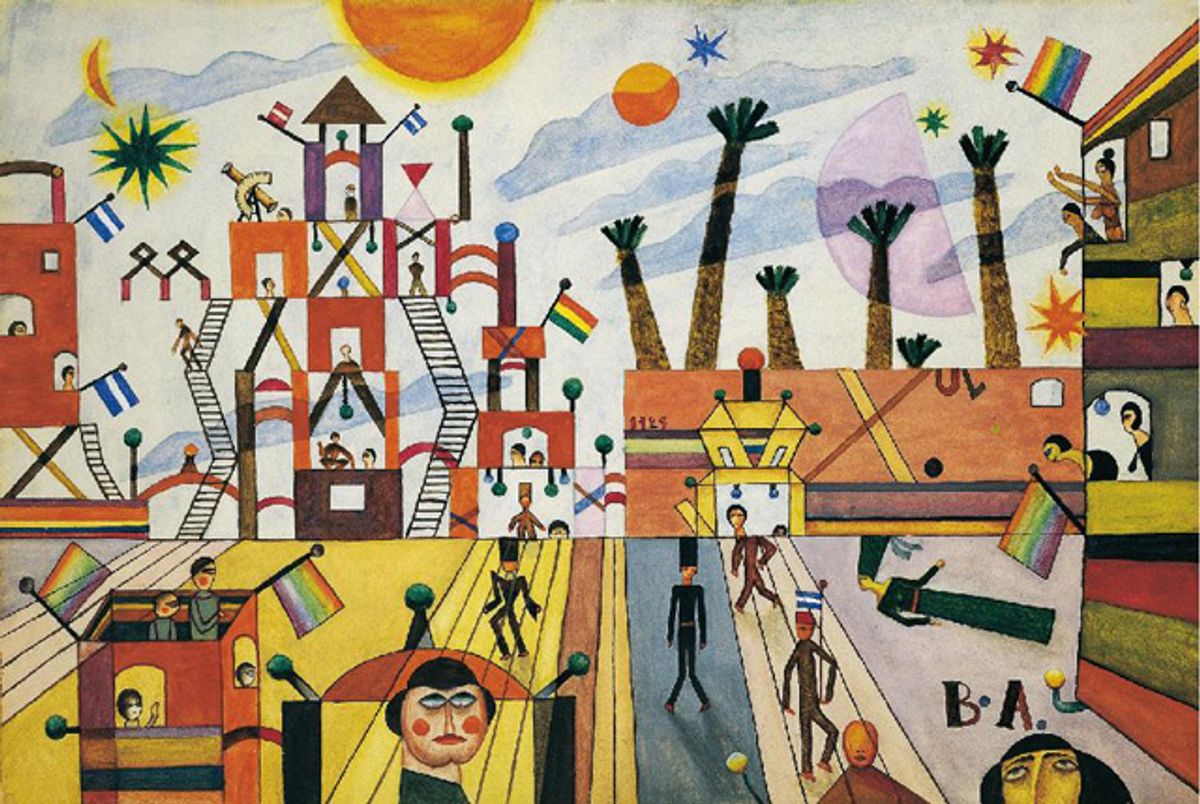

The artist had diverse interests, among them world languages, literature, mathematics, and religions; ancient and contemporary art; and the occult. One of his projects involved the creation of new universal languages he called Neo Creole and Pan Lengua. His interest in the visual aspects of these languages is evident in 1928 pencil drawings of vignettes for Borges’s essay “The Language of the Argentines.” The vignettes include Solar’s signature imagery: hybrid human-animal figures; geometric and architectural structures; cosmological, astrological, and occult signs; flags; and symbols drawn from various historical cultures and periods, such as ancient and pre-Columbian art.

Solar’s goal was to create intertwined linguistic and visual lexicons through works including his 1954 Tarot deck, for which he reinterpreted the Major Arcana by integrating visual elements from his own work with those of diverse cultural traditions and the occult. That he created his own deck is not surprising; this ancient divinatory tool incorporates knowledge of astrology, numerology, and occult systems, and books from his library, his diary, and astrological charts that he owned shed light on the extent of his knowledge of these things.

Also on view is a fascinating invented game known as Panajedrez, Panjuego, and Ajedrez criollo – or Panchess, Pangame and Creole chess. The wordplay reflects the multiple facets of the game: a visual, textual, and symbolic lexicon invented by the artist drawing from existing sign systems; a supremely challenging test of strategy made more complex by new rules; and a way to write or think about astrology, language, and mathematics. The relationship of this multilayered game and the artist’s works on paper is clear when one compares the two. The latter are colorful, delicate watercolors, comprised of a multiplicity of imagery that encourages the viewer to reflect on the beautifully rendered figures, signs, architecture, and landscapes. Both them and the chess game allude to the artist’s cosmopolitan and playful intellectual practice, in which the familiar is reinvented, the universal becomes local, and vice versa.

The exhibition includes Borges and Solar’s letters, manuscripts, and other documentary material presented alongside the works of art, demonstrating the impact of the pair’s longstanding friendship and their shared intellectual concerns. A number of vanguard magazines and photographs re-create the context in which the two friends worked in Buenos Aires, as well as the artistic, literary, and political debates of the time. Some of these magazines include vignettes by Solar designed for the publications, illustrations of his works, and texts by Borges. By including examples of archival documentation, print culture, as well as literary and art works, the exhibition presents a nuanced examination of the projects that inspired both friends. The innovative pairing introduces the work of an important vanguard artist while shedding new light on the renowned writer’s production. At the same time, the exhibition illuminates the links between the local and international networks in which both men worked.

Xul Solar is also on view at the Venice Biennale’s central exhibition, curator Massimiliano Gioni’s The Encyclopedic Palace, which includes historical and contemporary pieces by self-taught and professional artists. According to Gioni in an interview with Friezemagazine, “The Encyclopedic Palace,” a never realized architectural project for a museum by the self-taught artist Marino Auriti, inspired him because Auriti “blurs the distinction between the so-called outsider and the professional.” The term “encyclopedic” refers to the imagined museum’s contents: “all possible knowledge; a collection of the greatest discoveries of humanity.” Such frameworks are very much of the moment, as biennials repeatedly thematize variations on the relationships between the global and the local. As the oldest and most influential of these exhibitions, Venice has been criticized for some time for representing vestiges of the 19th-century projects of nationalism and European imperialism that marked its origins. This has now become a commonplace — a subject of knowing institutional critique by artists such as Allora and Calzadilla, who, at the 2011 United States pavilion, satirized the Olympics, US militarism, global financial, and travel networks in their exhibition Gloria.

These issues are also a source of anxiety for curators of the mega-exhibitions, who strive to demonstrate their own “global” artistic portfolios and generous cosmpolitanism. A recent post on Hyperallergic surveyed the geographic statistics for this year’s biennial: just over 75% of the artists are European and North American; seven artists from Latin American and Caribbean countries comprise 4.39% of the total. Gioni responded to such criticism by citing the following areas: Asia, South America, Nigeria, Ivory Coast, and Senegal. By responding in these ways, curators run the risk of identifying non-Western or Latin American artists as de facto representatives of their place of birth. Ironically, this may reaffirm the original framework of the Biennale, with its national representations.

Visitors to Venice will see examples of Solar’s Pangames – a Panchess set and Panlanguage cards, a folder with newspaper and magazine clippings, astrological charts, and a puppet representing an allegorical figure of Death. The latter reappears at the Americas Society in one of the Major Arcana cards in the artist’s Tarot deck. At the Biennale, however, Solar’s works are displayed at the Giardini in the Stirling Pavilion, site of the bookshop, rather than at the Padiglione Centrale. If the placement in the bookshop evokes the artist’s extensive library and intellectual curiosity, it also serves to separate his work from the main exhibition. Many people might not see it at all.

In any event, after seeing the show at the Americas Society, I wondered what might be lost when the artist’s complex work is only partially represented, as it is in Venice. Is his interdisciplinary project obscured when one sees documents, studies, or a game but not his drawings? And in omitting the drawings to emphasize the artist’s interest in the occult within an exhibition that includes works by self-taught artists and ritual imagery, might Xul be misunderstood as an eccentric mystic, working in isolation in Buenos Aires? This would be an unfortunate irony, since Xul Solar and Jorge Luis Borges were already investigating, enacting, and raising questions of the local and global in the early 20th century — questions that are often regarded as novel and groundbreaking today.

Xul Solar and Jorge Luis Borges: The Art of Friendship continues at the Americas Society (680 Park Avenue, Upper East Side, Manhattan) through July 20.

The Encyclopedic Palace continues at the Giardini and the Arsenale at the 2013 Venice Biennale (Venice, Italy) through November 24.

Shares