Besides, half the women in the prison system were trifling, street-level thugettes, and some things she just couldn’t flow with… She spent most of her days working out or working on her writing. For years, Nick had indulged in reading urban fiction novels until one day she came across a novel that should have put the author to shame with the way it was written. At that moment, Nick tossed the novel to the side, grabbed a pad and pen, and began to write. She became so engrossed with this new hobby that when she realized she had seven novels under her belt, she began to seek a publishing house who would publish her work.

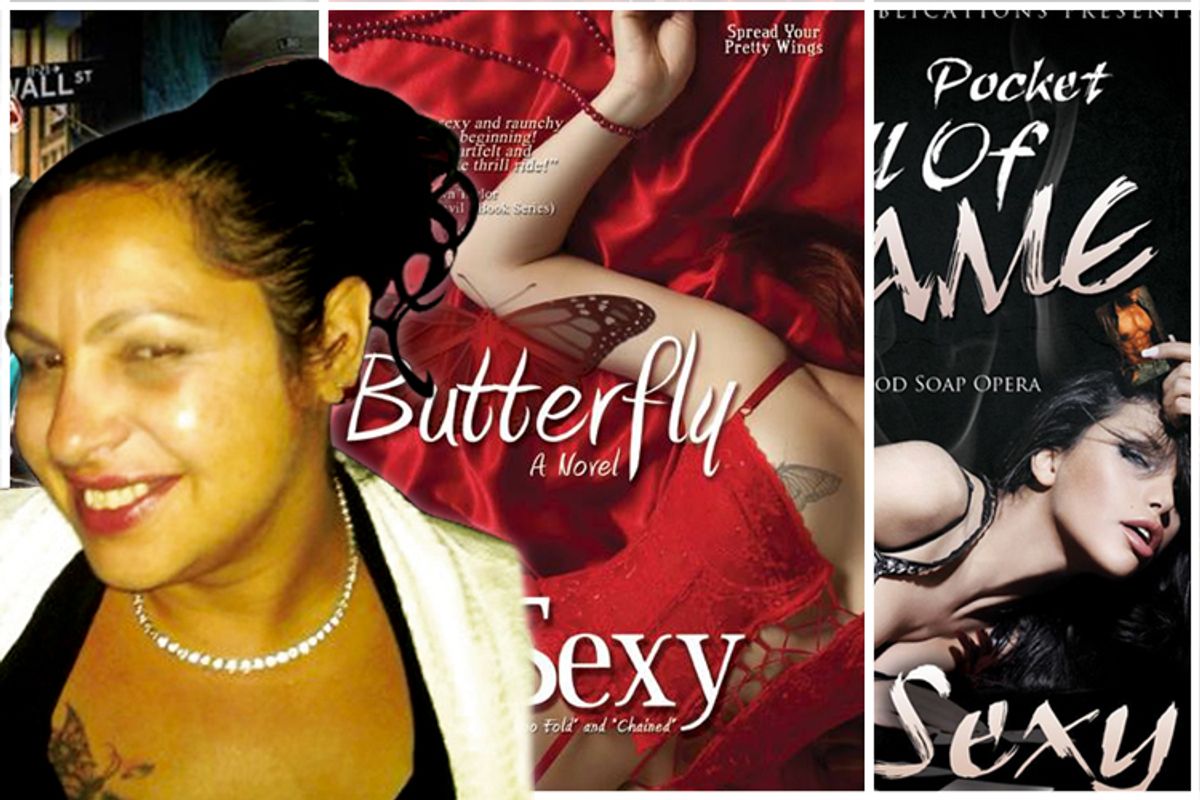

“Butterfly” – Sexy (Deborah Cardona)

Deborah Cardona sat, her thick black hair tied into a messy ponytail and a velour tracksuit accentuating her curves, eating Chinese take-out, at a table near the rear of the bookstore and lounge that she owned in East Harlem (it has since closed). Pictures of women kissing and fondling each other hung behind her, framing her strong features between models’ bare legs and lace-clad midriffs. In the front of the store, books were interspersed amongst the colorful sex toys and lubricants that lined the shelves, reminiscent of a wayward candy store. Between bites of General Tso's chicken, she explained her path from drug dealer to book dealer.

In 2007, Cardona, 47, was released from prison after serving a five-year sentence for dealing drugs. Like her character Nick, Cardona started reading the genre known interchangeably as street, urban or hip-hop fiction while in prison until she read a poorly-written novel and decided to write one of her own. “I’ve been writing ever since,” she said. In prison, she would sit with her college-ruled notebook and fill the sheets while the 50 other women inside talked, screamed, played cards or watched TV.

Urban fiction often tells stories of violence. Murder and prostitution sometimes replace love and marriage. Protagonists go to prison, and a happy ending means being alive by the end of the novel. Gangs reign, alcohol flows and drugs are currency. But these are also stories of friendship and hope. Where universities are an ultimate and the G.E.D. is a requisite to happiness. Written in a distinct vernacular with characters more often portrayed in music and movies, urban literature documents a culture that has been largely ignored by mainstream, literary America.

“Say you read my book and you’re going to be like, oh my god, these people really live like that out there? I’m introducing you to a different lifestyle,” explains Cardona.

If “music is the CNN of the hood,” as Terrell Blair, the owner of an urban book marketing company described it, then Cardona and her fellow authors are the Charles Dickenses of their land – spreading and commenting on the issues of their neighborhoods through the written word. “My whole thing was that I have a story to tell you,” Cardona explained at her East Harlem apartment, where she was selling sex toys to Blair’s wife for a “pleasure party,” her new business. Between discussing lube flavors and lingerie, Cardona mused on race: “You are the black boy next door. I live right next to you… but we all grew up in the same environment, so it’s not an African American thing anymore, and I opened the door for a lot of Latinos to start writing.”

***

Once released from prison, Cardona self-published her first novel, “Chained,” under her pen name, Sexy. “I love high heels,” Cardona enthused, as she recounted the origins of the name. Born and raised in East Harlem, Cardona would steal her mother’s pumps, slinging them into her backpack as she’d leave the house. Once safe on the streets, Cardona would slip them on, let her long hair loose and strut. Her nickname, Sexy, was born from those pumps, as the boys would catcall to her down Lexington and Park Avenues.

But those streets weren’t always kind to Cardona. “The selling of the drugs, hanging out in the projects, refusing to get a nine to five because the money’s much better on the street… becoming part of gangs. That’s the street life. Pimps, prostitution, stuff like that,” she said. Cardona’s mother raised her alone and worked nine to five. Cardona was lonely. “I went out to the street looking for, not excitement, because I was too young for that, but companionship,” she said.

Her first arrest came at age 18 or 19, she can’t remember exactly, for shoplifting. She had already been selling drugs for a year or two. Her first time in jail was at the age of 21 or 22 and she later spent time twice in state prison for selling drugs, until she was released in 2007, the same year she self-published her first novel.

“I think the books gave me a way of taking care of myself financially without having to go back to the street and I didn’t want to go back to the street in my heart. I didn’t want to live that life no more. I was tired,” explained Cardona.

She started on 125th Street in Central Harlem; she sold her own books and those of other urban authors. Then she opened up a bookstore in East Harlem. “Fuck 125th Street – I’m going to do it in my community,” she said, referring to Spanish Harlem.

She was successful. After all, she had sales skills.

“Let me tell you something. The way I hustle my books is the same way I used to hustle my drugs. I would literally throw my book in your face, and I would keep talking to you until you buy it.” The only difference? She got positive reactions from her books and her readers.

“I love it. It’s a rush.”

***

Vanessa Irvin Morris writes in "The Readers' Advisory Guide to Street Literature" that the genre dates back to the 1800s, when authors such as Dickens in “Oliver Twist” were writing about the harsh realities of living in poverty in an urban setting. “During the 20th century,” Morris writes, “street lit was primarily a European immigrant story and during the early 21st century, it is primarily an African American and Latino story…” In most circumstances, when someone refers to a book as “urban” it means a book that focuses on cultures that are traditionally marginalized.

In the prologue to Morris’ book, urban fiction author Teri Woods explained the importance of the genre: “These street lit books represent a voice of what was never to be spoken or told… not everyone can hear the cries of the inner city streets,” she wrote. “Street lit will always remind the human race of a people who were supposed to be forgotten, swept under a rug, put in a box—better yet a cell—never to have a voice, never to cry out, and never able to speak out against the injustice…” By writing in the voice of the inner city, with authors and readers who have experienced repression and injustice, this literary movement authenticates and validates this community.

Morris echoes these sentiments as she articulates why the genre has gained such popularity amongst its inner city readers: “Street lit,” she writes, “is a powerful conduit for readers finding an authentic voice within an American culture that otherwise keeps them marginalized and therefore silenced.”

A New York Times profile of legendary urban fiction author Donald Goines, who many see as the father of the genre, begins, “His was undoubtedly the path least traveled toward literary achievement: Pimp. Armed robber. Heroin addict.” But for Cardona and many other street authors, that path to literature isn’t so far-fetched.

In “Butterfly,” Cardona tells the story of corrections officer Déjà Padilla, who vies to become a rich and famous madam. A single mother who left her abusive husband to give her two daughters a better life, Padilla recruits women from the Albion Correctional Facility to become her prostitutes and encourages them to seek higher education during the day. When a prison warden, who is a frequent customer of Padilla’s brothel, attacks one of the women and is killed, Padilla’s dreams and newfound fortune are threatened. Of all her characters, Cardona says she sees herself most in Padilla: the strength, leadership and brains behind an operation to make herself a better life. But Cardona doesn’t glamorize the lifestyle. Instead, she said she demonstrates the dangers. “I write street lit because that’s the life I lived,” she explained. “I can’t write about the suburbs, because I haven’t lived in the suburbs.”

Shares