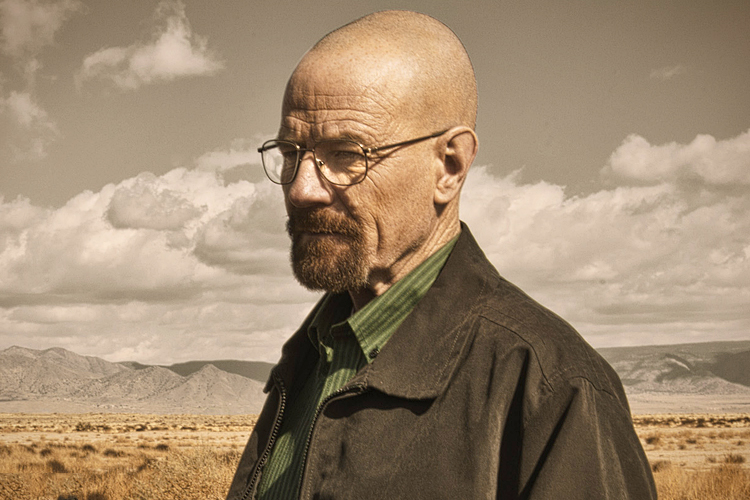

It is safe to say that as “Breaking Bad” comes to a close, Vince Gilligan’s series is the moment’s Best Show In the History of Television. Incredibly, the show isn’t even over yet, and it is already a cult classic, with all the attendant prop fetishization and tourism industries that come with such a designation. But as we approach the final episode, there’s an unanswered question: What makes the show so historically important?

Critics have rightly lauded the series for, among other things, its cinematography, its dialogue, its character development and its carefully constructed plot twists. Yet, in this much-vaunted new Golden Age of TV, there are plenty of programs with great visuals, terrific conversations, nuanced personalities and enticing stories — but most never achieve the same notoriety as the life of Walter White. Similarly, “Breaking Bad” is part crime drama, part satire of the legal system and part commentary on family dysfunction — but those narrative vectors are hardly unexplored territory in television. So what makes the story of Walter White so special?

Here’s a theory: Maybe “Breaking Bad” has ascended to the cult firmament because it so perfectly captures the specific pressures and ideologies that make America exceptional at the very moment the country is itself breaking bad.

The most obvious way to see that is to look at how Walter White’s move into the drug trade was first prompted, in part, by his family’s fear that he would die prematurely for lack of adequate health care. It is the kind of fear most people in the industrialized world have no personal connection to — but that many American television watchers no doubt do. That’s because unlike other countries, Walter White’s country is exceptional for being a place where 45,000 deaths a year are related to a lack of comprehensive health insurance coverage. That’s about ten 9/11’s worth of death each year because of our exceptional position as the only industrialized nation without a universal public health care system (and, sadly, Obamacare will not fix that).

Walter’s fear of bankrupting his family is also familiar. The kind of medical bills Walter faced are hardly rare in America — they are, in fact, the country’s single largest cause of bankruptcy. And again, this makes America exceptional because, alas, medical bankruptcies basically do not exist in the rest of the industrialized world.

Walter’s economic desperation is almost certainly fueled by his knowledge that a medical bankruptcy has particularly extreme consequences for an American family. He knows, for instance, that he lives in a country where his son and daughter’s academic success and his wife’s retirement security will be based primarily on the size of the family’s bank account. He also knows that the possibility of his family getting caught in crushing poverty is particularly acute in an America with a comparatively meager social safety net. And so he becomes obsessed with coming up with a way to give his family barrel loads of cash.

If this was where the narrative arc of “Breaking Bad” ended, it might be a 21st century version of “Falling Down” — but not much more. Walter, though, is far more than just a disgruntled government employee. He is the personification of the whole theory that America’s exceptional form of safety-net-free capitalism — and the desperation it breeds — truly does breed innovation and entrepreneurship. Think about it: Through his alter ego, Heisenberg, Walter’s desperation leads him to build a business from scratch that creatively destroys sclerotic monopolies and that ultimately delivers a superior product to consumers all over the world.

Heisenberg, in other words, reminds us that America’s unique brand of capitalism delivers exceptional productivity — but not necessarily in ways that we might want.

Still, economic desperation cannot fully explain Walter’s process of breaking bad. After all, while he does have cancer, he faces no more economic stress than most people in his economic situation who also face the illness — and most middle-class cancer victims don’t opt to cook meth. So what sets him apart and makes his story so representative of this moment’s zeitgeist? The answer is his total embrace of the most pernicious aspects of the American Dream mythology.

Unlike so many Americans, Walter White actually has a safety net. As a public school teacher, he actually has decent health insurance (even though as noted above, it may not be completely adequate for his illness, and may not prevent a medical bankruptcy). That is more than millions of his fellow countrymen can say. Also unlike most Americans, he has friends from his past who are willing to pay to get him the world’s most cutting-edge cancer treatments. But even with all that, Walter still chooses what he calls “the empire business” in an effort to live out the dominant mythology. More specifically, he rejects his friends’ offer of help and embarks on a flamboyant journey to live out the archetypal up-from-the-bootstraps story — the American Dream narrative on which our society bases its very definition of manhood. In the process, he also tries to live out the Aggrieved American White Guy Fantasy of thwarting his dark-skinned foreign competitors and claiming a market that he believes to be rightfully his.

Ultimately, all of these themes converge to raise the most harrowing questions of all — the taboo questions about whether we should really cherish the desperation, the greed and the every-man-for-himself ideologies that drive Walter White and that make American the industrialized world’s exception. It is the kind of question “Wall Street” asked back in 1987 when a badly broken Bud Fox dared to ask Gordon “Greed is Good” Gekko: “How much is enough?” It is the same question that “Breaking Bad’s” psychopathic murderer Todd recently posed to his neo-Nazi uncle when he asked: “No matter how much you got, how do you turn your back on more?”

In America, our culture too often offers up the same response as Gekko and Heisenberg. We too often say there is no such thing as “enough” and therefore you don’t ever turn your back on more.

Unlike any other television show before it, “Breaking Bad” dares to explore how such exceptional answers are at the root of so many of our problems. That alone makes the show more than just Important Television and more than merely exceptional. It makes it altogether unique.