My daughter has just turned six. Some time over the next year or so, she will discover that her parents are weird. We’re weird because we go to church.

This means—well, as she gets older there’ll be voices telling her what it means, getting louder and louder until by the time she’s a teenager they’ll be shouting right in her ear. It means that we believe in a load of bronze-age absurdities. It means that we don’t believe in dinosaurs.

It means that we’re dogmatic. That we’re self-righteous. That we fetishize pain and suffering. That we advocate wishy-washy niceness. That we promise the oppressed pie in the sky when they die. That we’re bleeding hearts who don’t understand the wealth-creating powers of the market. That we’re too stupid to understand the irrationality of our creeds. That we build absurdly complex intellectual structures, full of meaningless distinctions, on the marshmallow foundations of a fantasy. That we uphold the nuclear family, with all its micro-tyrannies and imprisoning stereotypes. That we’re the hairshirted enemies of the ordinary family pleasures of parenthood, shopping, sex and car ownership. That we’re savagely judgmental. That we’d free murderers to kill again. That we think everyone who disagrees with us is going to roast for all eternity. That we’re as bad as Muslims. That we’re worse than Muslims, because Muslims are primitives who can’t be expected to know any better. That we’re better than Muslims, but only because we’ve lost the courage of our convictions. That we’re infantile and can’t do without an illusory daddy in the sky. That we destroy the spontaneity and hopefulness of children by implanting a sick mythology in your minds. That we oppose freedom, human rights, gay rights, individual moral autonomy, a woman’s right to choose, stem cell research, the use of condoms in fighting AIDS, the teaching of evolutionary biology. Modernity. Progress. That we think everyone should be cowering before authority. That we sanctify the idea of hierarchy. That we get all snooty and yuck-no-thanks about transsexuals, but think it’s perfectly normal for middle-aged men to wear purple dresses. That we cover up child abuse, because we care more about power than justice. That we’re the villains in history, on the wrong side of every struggle for human liberty. That if we sometimes seem to have been on the right side of one of said struggles, we weren’t really; or the struggle wasn’t about what it appeared to be about; or we didn’t really do the right thing for the reasons we said we did. That we’ve provided pious cover stories for racism, imperialism, wars of conquest, slavery, exploitation. That we’ve manufactured imaginary causes for real people to kill each other. That we’re stuck in the past. That we destroy tribal cultures. That we think the world’s going to end. That we want to help the world to end. That we teach people to hate their own natural selves. That we want people to be afraid. That we want people to be ashamed. That we have an imaginary friend; that we believe in a sky pixie; that we prostrate ourselves before a god who has the reality status of Santa Claus. That we prefer scripture to novels, preaching to storytelling, certainty to doubt, faith to reason, law to mercy, primary colors to shades, censorship to debate, silence to eloquence, death to life.

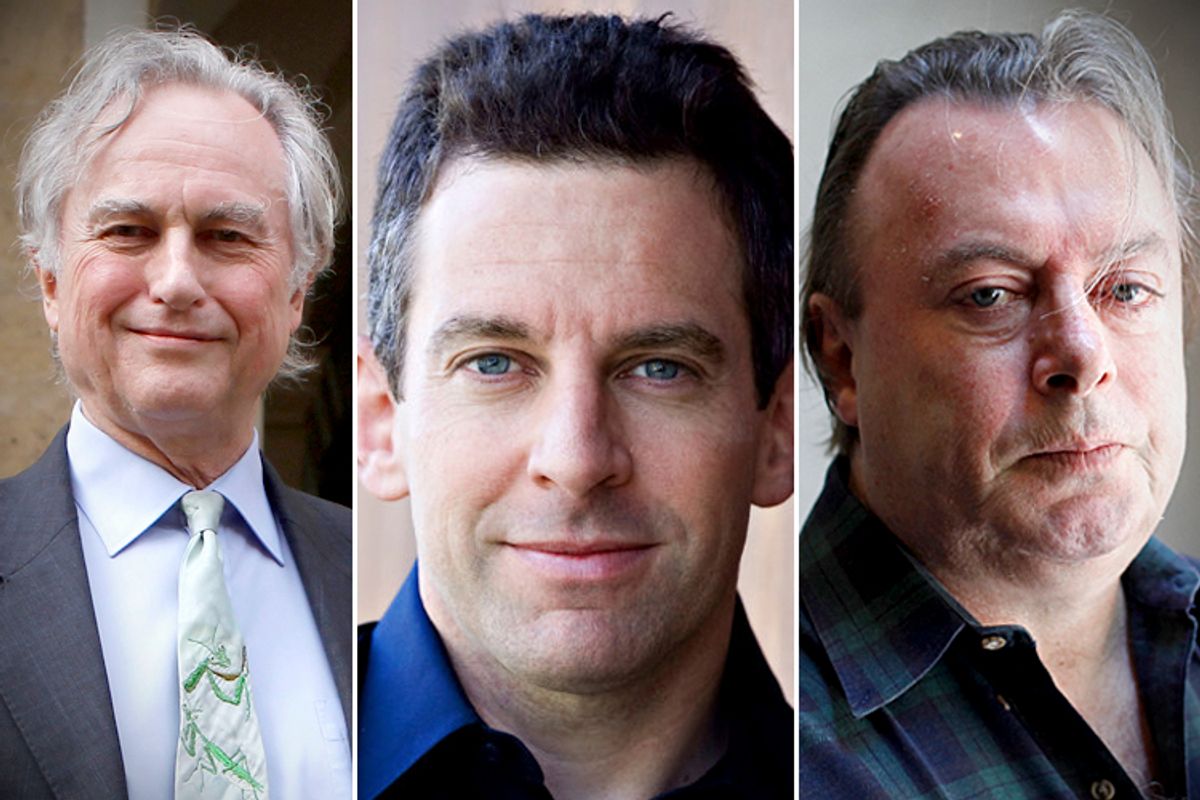

But hey, that’s not the bad news. Those are the objections of people who care enough about religion to object to it—or to rent a set of recreational objections from Richard Dawkins or Christopher Hitchens. As accusations, they may be a hodge-podge, a mish-mash of truths and half-truths and untruths plucked from radically different parts of Christian history and the Christian world, with the part continually taken for the whole (if the part is damaging) or the whole for the part (if it’s flattering)—but at least they assume there’s a thing called religion there which looms with enough definition and significance to be detested. In fact there’s something truly devoted about the way that Dawkinsites manage to extract a stimulating hobby from the thought of other people’s belief. The ones in this country must be envious of the intensity of the anti-religious struggle in the United States; yet some of them even contrive to feel oppressed by the Church of England, which is not easy to do. It must take a deft delicacy at operating on a tiny scale, like doing needlepoint, or playing Subbuteo, or fitting a whole model-railway layout into an attaché case.

No: the really painful message our daughter will receive is that we’re embarrassing. For most people who aren’t New Atheists, or old atheists, and have no passion invested in the subject, either negative or positive, believers aren’t weird because we’re wicked. We’re weird because we’re inexplicable; because, when there’s no necessity for it that anyone sensible can see, we’ve committed ourselves to a set of awkward and absurd attitudes which obtrude, which stick out against the background of modern life, and not in some important or respect-worthy or principled way either; more in the way that some particularly styleless piece of dressing does, which makes the onlooker wince and look away and wonder if some degree of cerebral deficiency is involved. Believers are people with pudding-bowl haircuts, wearing anoraks in August, and chunky-knit sweaters the color of vomit. Or, to pull it back from the metaphor of clothing to the bits of behavior that the judgment is really based on, believers are people who try to insert Jee-zus into conversations at parties; who put themselves down, with writhings of unease, for perfectly normal human behavior; who are constantly trying to create a solemn hush that invites a fart, a hiccup, a bit of subversion. Believers are people who, on the rare occasions when you have to listen to them, like at a funeral or a wedding, seize the opportunity to pour the liquidized content of a primary-school nativity play into your earhole, apparently not noticing that childhood is over. And as well as being childish, and abject, and solemn, and awkward, we voluntarily associate ourselves with an old-fashioned mildewed orthodoxy, an Authority with all its authority gone. Nothing is so sad—sad from the style point of view—as the mainstream taste of the day before yesterday. If we couldn’t help ourselves, if we absolutely had to go shopping in the general area of woo-hoo and The-Force-Is-Strong-In-You-Young-Skywalker, we could at least have picked something new and colorful, something with a bit of gap-year spiritual zing to it, possibly involving chanting and spa therapies. Instead of which, we chose old buildings that smell of dead flowers, and groups of pensioners laboriously grinding their way through “All Things Bright and Beautiful.” Rebel cool? Not so much.

And worst, as I said before, there is no reason for it. No obvious lack that this sad stuff could be an attempt to supply, however cack-handed. Most people don’t have a God-shaped space in their minds, waiting to be filled, or the New Atheist counterpart, a lack-of-God-shaped space, filled with the swirly, pungent vapors of polemic. Most people’s lives provide them with a full range of loves and hates and joys and despairs, and a moral framework by which to understand them, and a place for awe and transcendence, without any need for religion. Believers are the people touting a solution without a problem, and an embarrassing solution too, a really damp-palmed, wide-smiling, can’t-dance solution. In an anorak.

And so what goes on inside believers is mysterious. So far as it can be guessed at—if for some reason you wanted to guess at it—it appears to be a kind of anxious pretending, a kind of continual, nervous resistance to reality. It looks as if, to a believer, things can never be allowed just to be what they are. They always have to be translated, moralized—given an unnecessary and rather sentimental extra meaning. A sunset can’t just be part of the mixed magnificence and cruelty and indifference of the world; it has to be a blessing. A meal has to be a present you’re grateful for, even if it came from Tesco and the ingredients cost you £7.38. Sex can’t be the spectrum of experiences you get used to as an adult, from occasional earthquake through to mild companionable buzz; it has to be, oh dear oh dear, a special thing that happens when mummies and daddies love each other very much. Presumably, all of these specific little refusals of common sense reflect our great big central failure of realism, our embarrassing trouble with the distinction, basic to adulthood, between stuff that exists and stuff that is made up. We don’t seem to get it that the magic in Harry Potter, the rings and swords and elves in fantasy novels, the power-ups in video games, the ghouls and ghosts of Halloween, are all, like, just for fun. We try to take them seriously; or rather, we take our own particular subsection of them seriously. We commit the bizarre category error of claiming that our goblins, ghouls, Flying Spaghetti Monsters are really there, off the page and away from the rendering programs in the CGI studio. Star Trek fans and vampire wannabes have nothing on us. We actually get down and worship. We get down on our actual knees, bowing and scraping in front of the empty space where we insist our Spaghetti Monster can be found. No wonder that we work so hard to fend off common sense. Our fingers must be in our ears all the time—lalalala, I can’t hear you—just to keep out the plain sound of the real world.

The funny thing is that to me it’s exactly the other way around. In my experience, it’s belief that involves the most uncompromising attention to the nature of things of which you are capable. It’s belief which demands that you dispense with illusion after illusion, while contemporary common sense requires continual, fluffy pretending. Pretending that might as well be systematic, it’s so thoroughly incentivized by our culture. Take the famous slogan on the atheist bus in London. I know, I know, that’s an utterance by the hardcore hobbyists of unbelief, the people who care enough to be in a state of negative excitement about religion, but in this particular case they’re pretty much stating the ordinary wisdom of everyday disbelief. (Rather than, for example, rabbiting on about orbital teapots.) The atheist bus says, “There’s probably no God. Now stop worrying and enjoy your life.” All right then: which word here is the questionable one, the aggressive one, the one that parts company with actual recognizable human experience so fast it doesn’t even have time to wave goodbye? It isn’t “probably.” New Atheists aren’t claiming anything outrageous when they say that there probably isn’t a God. In fact they aren’t claiming anything substantial at all, because really, how the fuck would they know? It’s as much of a guess for them as it is for me. No, the word that offends against realism here is “enjoy.” I’m sorry—enjoy your life? Enjoy your life? I’m not making some kind of neo-puritan objection to enjoyment. Enjoyment is lovely. Enjoyment is great. The more enjoyment the better. But enjoyment is one emotion. The only things in the world that are designed to elicit enjoyment and only enjoyment are products, and your life is not a product; you cannot expect to unwrap it, and place it in an advantageous corner of your Docklands flat, and admire the way the halogen spots on your lighting track gleam on its sleek sides. Only sometimes, when you’re being lucky, will you stand in a relationship to what’s happening to you where you’ll gaze at it with warm, approving satisfaction. The rest of the time, you’ll be busy feeling hope, boredom, curiosity, anxiety, irritation, fear, joy, bewilderment, hate, tenderness, despair, relief, exhaustion and the rest. It makes no more sense to say that you should feel the single emotion of enjoyment about your life than to say that you should spend it entirely in a state of fear, or of hopping-from-foot-to-foot anticipation. Life just isn’t unanimous like that. To say that life is to be enjoyed ( just enjoyed) is like saying that mountains should only have summits, or that all colors should be purple, or that all plays should be by Shakespeare. This really is a bizarre category error.

But not necessarily an innocent one. Not necessarily a piece of fluffy pretending that does no harm. The implication of the bus slogan is that enjoyment would be your natural state if you weren’t being “worried” by us believers and our hellfire preaching. Take away the malignant threat of God-talk, and you would revert to continuous pleasure, under cloudless skies. What’s so wrong with this, apart from it being total bollocks? Well, in the first place, it buys a bill of goods, sight unseen, from modern marketing. Given that human life isn’t and can’t be made up of enjoyment, it is in effect accepting a picture of human life in which the pieces of living where easy enjoyment is more likely become the only pieces that are visible. You’d think, if you based your knowledge of the human species exclusively on adverts, that the normal condition of humanity was to be a good-looking single between twenty and thirty-five, with excellent muscle definition and/or an excellent figure, and a large disposable income. Clearly, there are exceptions, such as the lovey-dovey silver-agers who consume Viagra and go on Saga cruises, and the wisecracking moppets who promote breakfast cereal, but the center of gravity of the human race, our default condition, is to be young, buff and available. And you’d think the same thing if you got your information exclusively from the atheist bus, with the minor difference that, in this case, the man from the Gold Blend couple has a tiny wrinkle of concern on his handsome forehead, caused by the troublesome thought of God’s possible existence: a wrinkle about to be removed by one magic application of Reason™.

These plastic beings don’t need anything that they can’t get by going shopping. But suppose, as the atheist bus goes by, that you are the fifty-something woman with the Tesco bags, trudging home to find out whether your dementing lover has smeared the walls of the flat with her own shit again. Yesterday when she did it, you hit her, and she mewled till her face was a mess of tears and mucus which you also had to clean up. The only thing that would ease the weight on your heart would be to tell the funniest, sharpest-tongued person you know about it: but that person no longer inhabits the creature who will meet you when you unlock the door. Respite care would help, but nothing will restore your sweetheart, your true love, your darling, your joy. Or suppose you’re that boy in the wheelchair, the one with the spasming corkscrew limbs and the funny-looking head. You’ve never been able to talk, but one of your hands has been enough under your control to tap out messages. Now the electrical storm in your nervous system is spreading there too, and your fingers tap more errors than readable words. Soon your narrow channel to the world will close altogether, and you’ll be left all alone in the hulk of your body. Research into the genetics of your disease may abolish it altogether in later generations, but it won’t rescue you. Or suppose you’re that skanky-looking woman in the doorway, the one with the rat’s nest of dreadlocks. Two days ago you skedaddled from rehab. The first couple of hits were great: your tolerance had gone right down, over two weeks of abstinence and square meals, and the rush of bliss was the way it used to be when you began. But now you’re back in the grind, and the news is trickling through you that you’ve fucked up big time. Always before you’ve had this story you tell yourself about getting clean, but now you see it isn’t true, now you know you haven’t the strength. Social services will be keeping your little boy. And in about half an hour you’ll be giving someone a blowjob for a fiver behind the bus station. Better drugs policy might help, but it won’t ease the need, and the shame over the need, and the need to wipe away the shame.

So when the atheist bus comes by, and tells you that there’s probably no God so you should stop worrying and enjoy your life, the slogan is not just bitterly inappropriate in mood. What it means, if it’s true, is that anyone who isn’t enjoying themselves is entirely on their own. The three of you are, for instance; you’re all three locked in your unshareable situations, banged up for good in cells no other human being can enter. What the atheist bus says is: there’s no help coming. Now, don’t get me wrong. I don’t think there’s any help coming, in one large and important sense of the term. I don’t believe anything is going to happen which will materially alter the position these three people find themselves in. But let’s be clear about the emotional logic of the bus’s message. It amounts to a denial of hope or consolation, on any but the most chirpy, squeaky, bubble-gummy reading of the human situation. St Augustine called this kind of thing “cruel optimism” fifteen hundred years ago, and it’s still cruel.

Or for a piece of famous fluffiness that doesn’t just pretend about what real lives can be like, but moves on into one of the world’s least convincing pretenses about what people themselves are like, consider the teased and coiffed nylon monument that is “Imagine”: surely the My Little Pony of philosophical statements. John and Yoko all in white, John at the white piano, John drifting through the white rooms of a white mansion, and all the while the sweet drivel flowing. Imagine there’s no heaven. Imagine there’s no hell. Imagine all the people, living life in—hello?

Excuse me? Take religion out of the picture, and everybody spontaneously starts living life in peace? I don’t know about you, but in my experience peace is not the default state of human beings, any more than having an apartment the size of Joey and Chandler’s is. Peace is not the state of being we return to, like water running downhill, whenever there’s nothing external to perturb us. Peace between people is an achievement, a state of affairs we put together effortfully in the face of competing interests, and primate dominance dynamics, and our evolved tendency to cease our sympathies at the boundaries of our tribe. Peace within people is made difficult to say the least by the way that we tend to have an actual, you know, emotional life going on, rather than an empty space between our ears with a shaft of dusty sunlight in it, and a lone moth flittering round and round. Peace is not the norm; peace is rare, and where we do manage to institutionalize it in a human society, it’s usually because we’ve been intelligently pessimistic about human proclivities, and found a way to work with the grain of them in a system of intense mutual suspicion like the U.S. Constitution, a document which assumes that absolutely everybody will be corrupt and power-hungry given half a chance. As for the inner version, I’m not at peace all that often, and I doubt you are either. I’m absolutely bloody certain that John Lennon wasn’t. The mouthy Scouse git he was as well as the songwriter of genius, the leatherboy who allegedly kicked his best friend in the head in Hamburg, didn’t go away just because he put on the white suit. What seems to be at work in “Imagine” is the idea—always beloved by those who are frightened of themselves—that we’re good underneath, good by nature, and only do bad things because we’ve been forced out of shape by some external force, some malevolent aspect of this world’s power structures. In this case, I suppose, by the education the Christian

Brothers were dishing out in 1950s Liverpool, which was strong on kicks and curses, and loving descriptions of the tortures of the damned. It’s a theory that isn’t falsifiable, because there always are power structures there to be blamed when people behave badly. Like the theory that markets left to themselves would produce perfectly just outcomes (when markets never are left to themselves) it’s immune to disproof. But, and let me put this as gently as I can, it doesn’t seem terribly likely. We long to believe it because it’s what we lack. We dream of the peace we haven’t got, and to make ourselves look as if we do have it, we dress ourselves up in the iconography of the heaven we just announced we were ditching. White robes, the celestial glare of over-exposed film: “Imagine” looks like one part A Matter of Life and Death to one part Hymns Ancient and Modern. Only sillier.

A consolation you could believe in would be one that didn’t have to be kept apart from awkward areas of reality. One that didn’t depend on some more or less tacky fantasy about ourselves, and therefore one that wasn’t in danger of popping like a soap bubble upon contact with the ordinary truths about us, whatever they turned out to be, good and bad and indifferent. A consolation you could trust would be one that acknowledged the difficult stuff rather than being in flight from it, and then found you grounds for hope in spite of it, or even because of it, with your fingers firmly out of your ears, and all the sounds of the complicated world rushing in, undenied.

I remember a morning about fifteen years ago. It was a particularly bad morning, after a particularly bad night. We had been caught in one of those cyclical rows that reignite every time you think they’ve come to an exhausted close, because the thing that’s wrong won’t be left alone, won’t stay out of sight if you try to turn away from it. Over and over, between midnight and six, when we finally gave up and got up, we’d helplessly looped from tears, and the aftermath of tears, back into scratch-your-eyes-out-scratch-each-other’s-skin-off quarreling, each time with the intensity undiminished, because the bitterness of the betrayal in question (mine) was not diminishing. Intimacy had turned toxic: we knew, as we went around and around and around it, almost exactly what the other one was going to say, and even what they were going to think, and it only made things worse. It felt as if we were reduced—but truthfully reduced, reduced in accordance with the truth of the situation—to a pair of intermeshing routines, cogs with sharp teeth turning each other. When daylight came, the whole world seemed worn out. We got up, and she went to work. I went to a cafe—writer, you see, skivers the lot of us—and nursed my misery along with a cappuccino. I could not see any way out of sorrow that did not involve some obvious self-deception, some wishful lie about where we’d got to. (Where I’d got us to.) She wasn’t opposite me any more, but I was still grinding round our night-long circuit in my head. And then the person serving in the cafe put on a cassette: Mozart’s Clarinet Concerto, the middle movement, the Adagio.

If you don’t know it, it is a very patient piece of music. It too goes round and round, in its way, essentially playing the same tune again and again, on the clarinet alone and then with the orchestra, clarinet and then orchestra, lifting up the same unhurried lilt of solitary sound, and then backing it with a kind of messageless tenderness in deep waves, when the strings join in. It is not strained in any way. It does not sound as if Mozart is doing something he can only just manage, and it does not sound as if the music is struggling to lift a weight it can only just manage. Yet at the same time, it is not music that denies anything. It offers a strong, absolutely calm rejoicing, but it does not pretend there is no sorrow. On the contrary, it sounds as if it comes from a world where sorrow is perfectly ordinary, but still there is more to be said. I had heard it lots of times, but this time it felt to me like news. It said: everything you fear is true. And yet. And yet. Everything you have done wrong, you have really done wrong. And yet. And yet. The world is wider than you fear it is, wider than the repeating rigmaroles in your mind, and it has this in it, as truly as it contains your unhappiness. Shut up and listen, and let yourself count, just a little bit, on a calm that you do not have to be able to make for yourself, because here it is, freely offered. You are still deceiving yourself, said the music, if you don’t allow for the possibility of this. There is more going on here than what you deserve, or don’t deserve. There is this, as well. And it played the tune again, with all the cares in the world.

The novelist Richard Powers has written that the Clarinet Concerto sounds the way mercy would sound, and that’s exactly how I experienced it in 1997. “Mercy,” though, is one of those words that now requires definition. It does not only mean some tyrant’s capacity to suspend a punishment he has himself inflicted. It can mean—and does mean in this case—getting something kind instead of the sensible consequences of an action, or as well as the sensible consequences of an action. Getting something kind where you thought there’d only be consequences. It isn’t a question of some beetle-browed judge deciding not to punish you. It’s just as much a question of something better than you could have expected being slipped, stealthily, into a process that was running anyway. Mercy is—

But by now I would imagine that some of you reading this are feeling some indignation building up. I don’t know who you are, of course, my dear particular reader with this particular copy of the book in your particular hands, or what you think about religion. You may be an atheist with the light of combat in your eye, or a fellow-believer hoping for a persuasive account of what we share; you may be one of the large number of non-believers who are mildly, tolerantly curious about what faith can possibly feel like from the inside, in what seems to you to be a self-evidently post-religious world. Or you may fall into some different category altogether. I don’t know, and I hope you’ll excuse me if, in my urgent desire to talk back at some of the loudest and most frequent contemporary reactions to belief, I seem to be shoving you, when I say “you,” into company where you really don’t belong. In this case by “you” I mean all of you who, as I start to wax eloquent about mercy, are surging metaphorically to your feet with the strong sensation that I just rushed past something important. (“Skating fast over thin ice,” as Ralph Waldo Emerson put it.)

Fair enough: if I get to interrupt Mr. Lennon, you certainly get to interrupt me. Wait a minute, wait a minute, you say; never mind how you’re defining mercy. What about the way you’re defining religion? That’s religion, listening to some Mozart in a cafe? You were experiencing what we in the world of unbelief like to call “an emotion,” an emotion induced by a form of artistic expression which, to say the least, is quite famous for inducing emotions. You were not receiving a signal from God, or whatever it is you were about to claim; you were getting, if anything, a signal from Mr. Mozart, that well-known dead Austrian in a wig. I hope that isn’t your basis for religious faith, you say, because you’ve described nothing there that isn’t compatible with a completely naturalistic account of the universe, in which there’s nobody there to extend any magical mercy from the sky, just stuff, lots and lots of astonishing, sufficiently interesting stuff, all the way up from the quantum scale to the movement of galaxies.

Well, yes. By the same token, of course, what I’ve described is also completely compatible with a non-naturalistic account of the universe—but that’s not really the point, is it? The point is that from outside, belief looks like a series of ideas about the nature of the universe for which a truth-claim is being made, a set of propositions that you sign up to; and when actual believers don’t talk about their belief in this way, it looks like slipperiness, like a maddening evasion of the issue. If I say that, from inside, it makes much more sense to talk about belief as a characteristic set of feelings, or even as a habit, you will conclude that I am trying to wriggle out, or just possibly that I am not even interested in whether the crap I talk is true. I do, as a matter of fact, think that it is. For the record, I am not pulling the ultra-liberal, Anglican-going-on-atheist trick of saying that it’s all a beautiful and interesting metaphor, snore bore yawn, and that religious terms mean whatever I want them to mean. (Though I do reserve the right to assert that believers get a slightly bigger say in what faith means than unbelievers do. It is ours, after all. Come in, if you think you’re hard enough.) I am a fairly orthodox Christian. Every Sunday I say and do my best to mean the whole of the Creed, which is a series of propositions. No dancing about; no moving target, I promise. But it is still a mistake to suppose that it is assent to the propositions that makes you a believer. It is the feelings that are primary. I assent to the ideas because I have the feelings; I don’t have the feelings because I’ve assented to the ideas.

So to me, what I felt listening to Mozart in 1997 is not some wishy-washy metaphor for an idea I believe in, and it’s not a front behind which the real business of belief is going on: it’s the thing itself. My belief is made of, built up from, sustained by, emotions like that. That’s what makes it real. I do, of course, also have an interpretation of what happened to me in the cafe which is just as much a scaffolding of ideas as any theologian or Richard Dawkins could desire. I think—note the verb “think”—that I was not being targeted with a timely rendition of the Clarinet Concerto by a deity who micromanages the cosmos and causes all the events in it to happen (which would make said deity an immoral scumbag, considering the nature of many of those events). I think that Mozart, two centuries earlier, had succeeded in creating a beautiful and accurate report of an aspect of reality. I think that the reason reality is that way, is in some ultimate sense merciful as well as being a set of physical processes all running along on their own without hope of appeal, all the way up from quantum mechanics to the relative velocity of galaxies by way of “blundering, low and horridly cruel” biology (Darwin), is that the universe is sustained by a continual and infinitely patient act of love. I think that love keeps it in being. I think that Dante’s cosmology was crap, but that he was right to say that it’s “love that moves the sun and all the other stars.”* I think that the universe is its own thing, integral, reliable, coherent, not Swiss-cheesed with irrationality or whimsical exceptions, and at the same time is never abandoned, not a single quark, proton, atom, molecule, cell, creature, continent, planet, star, cluster, galaxy, diverging metaversal timeline of it. I think that I don’t have to posit some corny interventionist prod from a meddling sky fairy to account for my merciful ability to notice things a little better, when God is continually present everywhere anyway, undemonstratively underlying all cafes, all cassettes, all composers; when God is “the ground of our being,” as St Paul puts it, or as the Qur’an says with a slightly alarming anatomical specificity, when God “is as close to you as the veins in your own neck.”

That’s what I think. But it’s all secondary. It all comes limping along behind my emotional assurance that there was mercy, and I felt it. And so the argument about whether the ideas are true or not, which is the argument that people mostly expect to have about religion, is also secondary for me. No, I can’t prove it. I don’t know that any of it is true. I don’t know if there’s a God. (And neither do you, and neither does Professor Dawkins, and neither does anybody. It isn’t the kind of thing you can know. It isn’t a knowable item.) But then, like every human being, I am not in the habit of entertaining only the emotions I can prove. I’d be an unrecognizable oddity if I did. Emotions can certainly be misleading: they can fool you into believing stuff that is definitely, demonstrably untrue. But emotions are also our indispensable tool for navigating, for feeling our way through, the much larger domain of stuff that isn’t susceptible to proof or disproof, that isn’t checkable against the physical universe.* We dream, hope, wonder, sorrow, rage, grieve, delight, surmise, joke, detest; we form such unprovable conjectures as novels or clarinet concertos; we imagine. And religion is just a part of that, in one sense. It’s just one form of imagining, absolutely functional, absolutely human-normal. It would seem perverse, on the face of it, to propose that this one particular manifestation of imagining should be treated as outrageous, should be excised if (which is doubtful) we can manage it.

But then, this is where the perception that religion is weird comes in. It’s got itself established in our culture, relatively recently, that the emotions involved in religious belief must be different from the ones involved in all the other kinds of continuous imagining, hoping, dreaming, etc., that humans do. These emotions must be alien, freakish, sad, embarrassing, humiliating, immature, pathetic. These emotions must be quite separate from commonsensical us. But they aren’t. The emotions that sustain religious belief are all, in fact, deeply ordinary and deeply recognizable to anybody who has ever made their way across the common ground of human experience as an adult. They are utterly familiar and utterly intelligible, and not only because the culture is still saturated with the spillage of Christianity, slopped out of the broken container of faith and soaked through everything. This is something more basic at work, an unmysterious consanguinity with the rest of experience.

It’s just that the emotions in question aren’t usually described in ordinary language, with no special vocabulary; aren’t usually talked about apart from their rationalization into ideas. That’s what I shall do here. Ladies and gentlemen! A spectacle never before attempted on any stage! Before your very eyes, I shall build up from first principles the simple and unsurprising structure of faith. Nothing up my left sleeve, nothing up my right sleeve, except the entire material of everyday experience. No tricks, no traps, ladies and gentlemen; no misdirection and no cheap rhetoric. You can easily look up what Christians believe in. You can read any number of defenses of Christian ideas. This, however, is a defense of Christian emotions—of their intelligibility, of their grown-up dignity. The book is called Unapologetic because it isn’t giving an “apologia,” the technical term for a defense of the ideas.

And also because I’m not sorry.

Excerpted from "Unapologetic: Why, Despite Everything, Christianity Still Makes Surprising Emotional Sense." Copyright © 2013 by Francis Spufford. Reprinted with permission from HarperOne, a division of HarperCollinsPublishers.

Shares