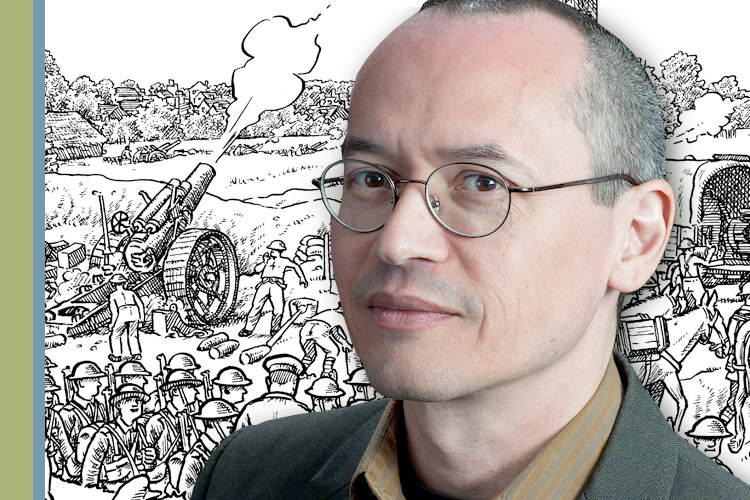

World War I is an unusual topic for a graphic novel — but Joe Sacco, the artist behind “The Great War,” is an unusual fellow.

The history lover and cartoonist has produced a foldout panorama that depicts the first day of the Battle of the Somme. Sacco, who’s been compared to trailblazing comic artists Art Spiegelman and R. Crumb, breaks down the day’s events: the grinding progress of the British, the exploding shells that will spell those soldiers’ doom.

Sacco’s work has largely been journalism about contemporary war zones; his past books have included comics about Palestine and Bosnia. But “The Great War,” for its historical remove as well as for its overwhelming sweep, is something different entirely. Sacco told Salon about how he uses images to communicate the horrors of the Western Front. “You’re inside it, and with the multiple images, you’ll hopefully get an idea of the atmosphere.”

The artist accepts the term “graphic novel,” one that’s come to be applied to comics that are perceived as more “serious.” But he noted that he didn’t mind being seen as a “comics artist.” “I was quite content with the word ‘comic book.'” A book this evidently serious and one that’s the product of so much work clearly isn’t just meant to entertain. But its dynamism and visual sweep rank with the best of what comic books, which at their best create immersive universes, have historically done.

You’ve been frequently compared to other graphic novel artists. Is that just because there are so few that are as prominent as you are, or do you think that you are really like, say, Art Spiegelman?

I mean, I wouldn’t know how to stack myself up against a genius like Art Spiegelman. I don’t know if I would. I mean, Art was an inspiration in the sense that what he did with “Maus” was pretty much groundbreaking. And if it weren’t for someone like him and his book, the doors might never have opened. As far as the way I draw, that’s probably most influenced — the most influence I have is from Robert Crumb, as far as drawing goes.

I’m wondering what you think of the term “graphic novel.” Is it one you embrace?

I don’t particularly care for it. I realize now that that battle is lost. My concern then — and even I, when people say, “What do you do?” and I’ll say, “I’m a cartoonist,” they get confused by what that means; I’ll say “graphic novel,” because that’s terminology that they understand. But I don’t like it, just because I think most of my work has been not a novel, not fiction, in other words, so I was quite content with the word “comic book” — but I understand that even that carries some baggage with it.

Right, it seems like either way, there’s some valence that people may or may not be happy with.

And I was — you know, I grew up with the term “comic books,” it didn’t bother me, and “graphic novel” always seemed like a way of making adults feel like they weren’t being puerile by buying these things.

I’m interested as well in what illustrations allow you to do in journalism and history that the written word doesn’t. What would you say are the advantages to conveying stories this way?

Let me preface it by saying I think every medium has its strengths. But I think illustrated work puts the reader directly into a picture. You open up, let’s say, a comic book, and I’ve drawn a Palestinian refugee camp — you’re inside it, and with the multiple images, you’ll hopefully get an idea of the atmosphere. As a cartoonist, you’re concentrating on giving visual information — especially in the background — that can be conveyed by multiple images. And things follow the reader around. You know, the architecture will follow the reader from one panel to another, so it becomes part of the atmosphere that the reader is imbibing. With the written word, you can describe the architecture, but you’re not going to keep mentioning it as a figure is walking down the street, you’re not going to keep mentioning what the background is. With comics you can do that.

It’s almost subliminally reminding people of things over and over.

Yeah, but without hitting them over the head — it’s just background information. The other thing I think a comic does well is that it can take the reader into the past, very seamlessly. Because your drawing style is the same now as if you’re drawing something a hundred years ago, and so the reader has an easier transition, which can be difficult to do with a documentary film; sometimes documentary film relies on acting to bring the past to life, and that always seems strange — it rubs up against the nature of documentary film.

And often if you lay photographs side by side — let’s say a modern photograph and a photograph from 150 years ago, or 100 years ago – -the difference in that technology makes it apparent that it was the past, that was another time. For me, I’m very interested in organic connections between the present and the past. So the less difference there is in people’s minds for the present and the past, the better it is, as far as I’m concerned. And finally, I’ll say this: Drawing helps you look at very difficult things. It might be very difficult to look at some of the things humans do to other humans if it was a photograph or if it was filmed. Whenever I see some of those sorts of films, it’s my natural inclination to turn away because it’s so real. Drawings allow for a certain filter, I think, that allows a reader to look.

World War I was such a notoriously violent war. Is that part of why you chose to do this? I know that your work is generally more reporting on contemporary events, so I’m wondering how it was that you became interested in this historical event.

I’ve been interested in historical events for a long, long time; pretty much all I read is history. As far as the First World War goes, I’ve been interested in that since I was a boy. I grew up in Australia, and over there World War I is very prominent in the national consciousness because of the Gallipoli landings.

And I remember the commemorations on Anzac Day, the day to commemorate the landings, which would take place, and listening to the stories over the school loudspeaker systems about soldiers at Gallipoli. I mean, that was sort of a yearly feature. So that stuck in my head. I also just had books about the First World War when I was little, that got me somehow intrigued and started me down this lifelong path of reading books about the First World War, partly because of the sheer strange technical developments of the First World War — the use of spy planes, poison gas, the first use of tanks. When you’re a boy you’re just sort of fascinated by that sort of stuff, in some ways, and I’ve been reading about this sort of thing for a long, long time. And in a way, when this project was suggested to me — it wasn’t really initiated by me — it just seemed like a natural fit, like something I should do because I’ve spent so much time obsessing over the First World War. Maybe it was time to redeem that interest, redeem that voyeuristic little boy, and actually produce something from all that reading and all that thinking.

Were you finding things out as you went along that you newly wanted to put in and give its due?

There are all kinds of aspects of the war that I didn’t know that much about. I’d never concentrated that much on the whole logistical thing, and so it was very impressive — this whole idea of cranking up a battle like this one — it’s enormous. It’s a huge human endeavor. You can question the results, and of course I do, but it’s a massive human undertaking, and I wanted to give some sense of the scale of that. There were many little details, of course, that I didn’t know much about, as far as — one thing is you see pictures of horses in the First World War, but then you realize how many horses they had and how vital they were, and you realize, “Oh, I have to draw a lot of horses.” It’s more about drawing horses than it is about drawing trucks.

Right, and I’m kind of curious: Is there an ideal way — because there are these patterns that reiterate — that someone should read or consume this? Should you look at it all at once? Should you kind of go through in a very methodical way? How do you envision your reader consuming this work?

It’s not a question I thought of while I was doing it, but I imagine there are a number of ways, and the two I can think of is 1) just to lay it out as far as you can and just walk across it and sort of soak in the whole thing in one go, but then probably I hope people will take time and look at some of the details. Because even though this is the story of humanity in a mass, there are also many individual stories going on. I’ve tried to individuate people as much as possible, and there are parts where you can almost cut out the story of what’s going on with one or two individuals here or there, whether they’re talking to each other or have a different reaction to certain things — there are a lot of little stories going on in this big picture.

“Favorite” is such a crass way to describe such an element of the war, but which littler stories, in particular, are you most proud of including?

I think in the line, if you look at the picture, the line toward the field kitchen, there’s one soldier who’s taken a piece of bread that he shouldn’t take, and his mates are laughing. I’m interested in the sort of, in these little stories, I’m making them up as I go along — they just sort of come to me as I’m drawing. That, to me, is a way of bringing life to those people. They’re not planned out one by one; they sort of take life as I’m drawing them. They become their own little spontaneous story.

These stories, then; there’s nothing like that in the history you found? Are these individual stories works of imagination?

To me, I think this is a work veering on the artistic side, as opposed to the strictly journalistic side, in that way. Although journalism obviously informs how I’ve approached this, in that I’m interested in getting the details right so that the reader can have as true an experience as I can manage it. But with things like that, you just imagine how humans would behave in these sorts of situations and you put yourself in their place to some extent, and you imagine it. And then, of course, I’ve read enough books — enough first-person accounts — maybe there’s no one that said, “I stole a piece of bread,” of course not, but you realize there are many different reactions going into a battle like this. There’s fear, there’s enthusiasm, there’s all kinds of things to show.

What do you hope your readers take from this in terms of a lesson? Is the book even intended that way?

I want the average person, who probably doesn’t know much about the First World War, let’s say, to have some sort of visceral sense of the first day of the Battle of the Somme, which in many people’s eyes epitomizes the futility of so much of this war. From my standpoint, what impressed me the most in drawing it was drawing the soldiers marching up; many of the troops were volunteers at this point, this was not a conscript army, and there was a great enthusiasm still. A lot of these soldiers wanted to get into the fight, and that sort of enthusiasm — as I’m drawing it, I’m thinking about it. I’m thinking about our capacity to sort of be enthusiastic for these proposals that are rather — what’s the word? It’s a great unknown going into war, and it’s strange how we put ourselves into these positions and, in a lot of ways, the masses blame the generals and the politicians for a while — but often people get behind these things too. Then it meets reality, and that’s what I’m trying to show. I want to show that enthusiasm meeting reality. That, to me, is sort of a lesson that you can take, or that I take, anyway, when I’m drawing something like this. The great thing about drawing is that it gives you the luxury to think about it because you’re spending so much time.

You can contemplate as you’re doing it, each second.

That’s the best thing about it, to me. Often I’m thinking about what I’m getting out of it. People ask, “What do you want the reader to get out of it?” That’s the secondary notion. Of course, I want the reader to feel something, too, but to me, when I’m doing it, I’m learning. It’s not like drawing is giving me answers; sometimes the act of drawing gives me questions. Anyway, it lets me think about those questions.