The most prolific blurber in publishing has set his pen to a longer project -- a memoir.

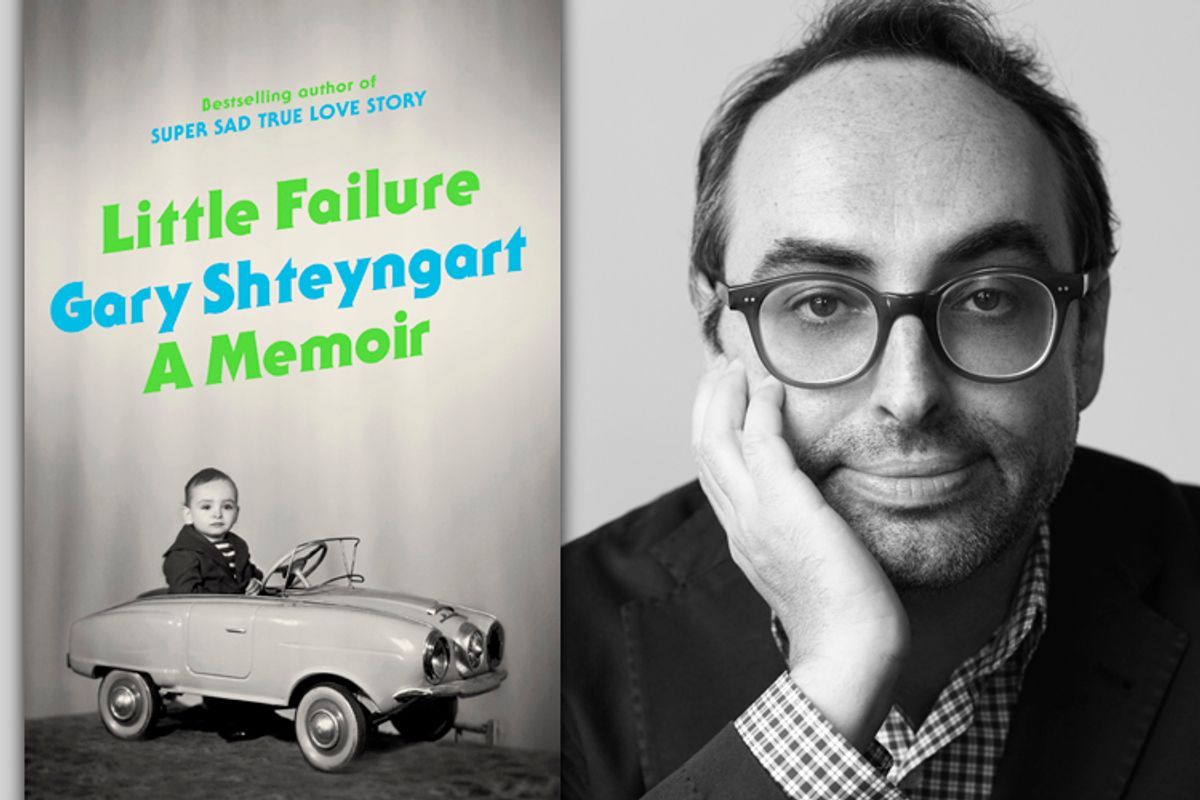

The novelist Gary Shteyngart has just published the book "Little Failure," about the years following his childhood emigration from Russia to New York; it's full of stories of striving both to write and to be understood, to become a man and an American. Previously the author of three well-received novels, Shteyngart is well-known and gently chided for the manner in which he will seemingly put his name on just about any book cover with exuberant praise.

His longer stuff has tended to be wildly satirical -- sometimes verging into the melancholy, as in "Super Sad True Love Story," his 2010 dystopian romance set in a post-literacy world. But in the process of writing "Little Failure," he said, Shteyngart discovered just how much that novel and its two predecessors ("The Russian Debutante's Handbook" and "Absurdistan") owed to the details of his life as a Russian Jew from New York; he plans to, in his next novel, cover entirely new territory. "It could be a major failure on my part if all I can write about is Russian Jews in Queens," he said, "in which case I’ll come right back to it." After all, he feels little patriotic connection, by now, to Putin's Russia: "I’m just trying to save Brooklyn."

Shteyngart, driven by nature thanks to his immigrant parents, discussed competitiveness and the literary vs. commercial fiction debates with Salon. And as for those blurbs? He's waiting until people wake up: "There have been so many of them that the market value of them may have plunged as well, so hopefully someday people will stop asking for them."

You're a person well-known for your novels now publishing a memoir. Was there a moment that you felt as though you’d lived enough life that you could finally have a story to write?

The answer to that question is that there's been enough life after the stuff I write about to be able to write about it … There is enough difference at age 41 from what I'm writing about. At the same time, I’m not old enough that I can’t remember anything, which is the sweet spot.

It’s interesting that it largely leaves aside the stuff that happens later on in life as a novelist of huge repute and acclaim. I wonder if you would ever be interested down the road in writing a memoir of your life today.

I’d wouldn’t want to say never, but the life of a working writer is pretty boring. You wake up, you roll around in bed, you go for a drink, it’s very boring. The concepts that I grew up with … Some writers continue moving, fighting well into their 50s, 60s -- what you’re looking for is conflict when you write. There was plenty of conflict when I was growing up, but right now I’m a settled, boring guy. I don’t see the conflict right now.

Something that haunts your work is concern for the future and how technology affects reading. On the occasion of the publication of your newest book, I’m wondering if there is any point in writing a book on paper anymore?

Well, I think that technology is making us ... Our attention span is shorter, even I have trouble opening up a gigantic book and getting right into it. I find that when I travel somewhere and there is no Wi-Fi and no connection that I can finally get into a book and read it from cover to cover and really get into the way it’s structured and the narrators and appreciate it in a way that I used to appreciate books all the time. So, yes, absolutely, that makes it completely different.

Do you feel as though being an immigrant to America has affected your writing of fiction and how has it changed over time?

You’re a little bit hungrier -- the fact that you have made the choice to become a writer, it’s difficult for anyone to make that choice. The fact that it doesn’t pay anything, there is a lot of difficulty ... But when you have immigrant parents, there’s even more of that feeling of “oh my God you need to succeed.” It’s a tough choice to make for anyone, but here, you feel that if you fail, you’ve not only betrayed yourself, but also the people who have done so much to bring you to this country and given up so much of their own culture. That’s the feeling that a lot of writers, and a lot of immigrants, have. The next generation can do whatever it wants, but you have to continue the upward mobility that your parents brought you here to enjoy.

Do you feel as though you’re comfortable with the amount of success and acclaim you’ve received -- or are you still striving?

I feel as I age -- I think I’ve worked hard. To put it in terms an immigrant mother would have loved, I’ve worked hard. I haven’t slacked off, I’m still doing my best. But I don’t feel like I can rest on my laurels, if that’s what you’re asking. I feel like there is a lot more to come. In a sense, writing this memoir was my attempt to clear the palate a little bit. Because after this, the fourth book -- the three books before have had immigrant, Russian Jewish immigrant protagonists. Time to move on, maybe do a character who is not a Russian Jewish male.

It’s interesting. Not to bring up Philip Roth unduly, but this is a person who had strong interest in exploring his ethnic background and whose attempts to move beyond it weren’t always successful.

That’s true and when Roth left Newark in a sense he spent a couple of novels doing social realism out in the Midwest. It could be a major failure on my part if all I can write about is Russian Jews in Queens -- in which case I’ll come right back to it. But I want to try something different right now -- and we’ll see what happens with the next book.

But for now, I’m really happy to have written a book that really exposes a lot of what my life was like and book that is really a microcosm of the 20th century, the last half of it, in that it’s one failed superpower and a child moving from one failed superpower to a country that is already beginning, with the oil shock, to stumble as well.

Obviously, you left Russia at such a young age -- but with the nation in the news, I wonder if you feel a connection to the nation or worry about it.

If you take the long view on Russia, it’s really always been a disaster. It had the worst feudalism in Europe; it had the worst socialism in Europe when that came around. Now it has sort of the worst form of capitalism and hypocrisy in that country. It’s very ill-fated. Nothing good seems to happen to it. One can go into various reasons for why that may be -- the geographical immensity of it, the way it was cut off from the renaissance, the way it was invaded by the Mongols. There are just so many geographic and geopolitical ways to look at it. I don’t know why. It’s just not a happy place. It doesn’t provide a good civil society for its citizens and its economy is dependent on oil and natural gas and resources. It’s not an inventive economy. It’s constantly run by one plutocrat or one dictator or another. It can’t seem to catch a break.

It makes it, in that way, an interesting source of literary inspiration.

That’s why so much literature comes out of that, I think: There’s all this despair. Russia’s writers are some of its greatest patriots; they want to read Russia, in a way. They want to save Russia. I think that’s a very Dostoyevskian outlook, but it’s very hard to do.

Do you put yourself in that Dostoyevskian …

No, I’ve left Russia. I’m just trying to save Brooklyn.

When I was in college, I was assigned a great deal of expatriate or immigrant fiction. I’m wondering if you consider your work as part of that tradition, or if you see any commonalities with the group of expatriate writers.

I do. I think right now there are just so many writers who are writing about stuff that doesn’t even fall into the rubric of immigrant fiction, but rather global fiction. It’s the world, people who come here, you used to emigrate, now you just bounce around the world and it’s a very different mentality. So it’s people who feel more comfortable on a plane going somewhere than their actual destinations.

You are known as a uniquely generous person when it comes to helping other writers, and one of those ways is providing your name for a book jacket blurb. I’m wondering the degree to which you think your blurb has an impact, at this point.

It’s true that these blurbs, there have been so many of them that the market value of them may have plunged as well, so hopefully someday people will stop asking for them. They’ll see that there is absolutely no need for them because there is one in every book.

I was wondering, given your hunger to succeed, if it expresses itself today as competitiveness with other writers. Do you feel a sense of competition when you read a novel that is really good?

No, no. That’s something I wanted to talk about because I feel like I haven’t encountered this in the world. And I don’t really get it, because what we do is already under siege in the sense that the market, not that many people read anymore, so I always thought that we should band together and be incredibly supportive of one another. I’m incredibly honored by the number of blurbs I get to do; I was incredibly honored by the blurbs I got for this book from people like Mary Karr, Zadie Smith, Carl Hiaasen. That’s amazing. That’s the right place where we should be supporting one another and encouraging each other’s work. In the past I wrote two book reviews that were really snarky, and I’m really sorry about that, because there was no reason for me to do that other than to indulge my own self-importance.

I found it interesting to hear you say that, because I was surprised to see you come up in the New Yorker this week in a profile of the novelist Jennifer Weiner; she would seem to have criticized the press coverage of "The Russian Debutante's Handbook" in the past. Do you think that there is room in the market you’re describing for authors of what’s commonly known as "commercial fiction" and "literary fiction" to band together?

Well, look: There’s a lot of literary fiction that’s worse than commercial fiction. These are just different ways to write. There are definitely different expectations from commercial fiction than literary fiction. But when commercial fiction is successful, I think literary fiction can benefit. I think they can both advance together. I love reading stuff that people would consider commercial fiction, I think some of it is definitely good.

In your book, there's a line where you are staging your apartment for a girl to come over and you try to make sure to hide like the most aggressively macho books and know that she is looking for a Jeanette Winterson book. Have your reading interests changed over time?

Have my reading habits changed over time? Yeah, I think they have. When I was growing up, I was reading a lot of male fiction, if you can call it that. I was up to my neck in Saul Bellow, which was wonderful and was very instrumental but I think I’ve gone, like most people I think I’ve expanded my range quite a bit. When you’re young you focus on things that are incredibly important to you and read, God knows, every Nabokov that’s ever been written. But then, it is time to move beyond that little place where you live and I’ve been doing that; I’m so curious to see so many people send me books now it’s exciting to go to the mailbox and see a work of Croatian fiction.

You teach writing at Columbia -- talk to me about the financial requirements that are needed to get an MFA and the degree to which the MFA has changed over time as a direct line to publishing a book.

It’s a tough thing. Because the MFA creates an environment that is amazing. People spend two years writing and reading and living the life of the writer. But it can also create narratives that are quite similar because it’s done by committee, in a way. You’re, unless you’re completely sure of your vision or the strength of your work, you may get worried.

I’ll give you an example: When I was doing my MFA, my mentor at Hunter College was Chang-rae Lee. And he got me a book deal before I had even started class. I started workshopping the book, in pretty much the way it was going to appear. And the criticism was horrifying! The class just -- a lot of the class really hated it. If I didn’t know I already had a book deal, I probably would have tried to sort of, you know, please people more. I would have tried to maybe curtail some of the satire and take away some of the humor and make it more like other books that are out there. So it’s possible for the MFA system to do that. As a teacher my goal is to find someone’s voice, to sort of identify the real strength of the voice, and to tell them to amp that up instead of trying to create stuff that merely sounds good or clever or technically superior.

In light of the kind of stresses imparted upon you by your parents, do you now look back at your first three novels and deem them successes or little failures or big failures?

When I finished and reread the three books I had written after I finished writing "Little Failure," I was shocked by how much stuff I had taken from the autobiographical back story without even knowing it, second nature. I almost felt when I went into this stupor of writing, you get into this kind of zone, not like a Rob Ford stupor, but mentally, you’re in a zone where you don’t even fully articulate where your inspiration comes from and that’s it. I had been using me in ways I didn’t even realize -- and I thought this could be a kind of letting go of things. I could use all this material up and have a fire sale, everything must go, and then maybe that will allow me to move on and at least come up with a title for one book.

Shares