By 2009, California’s prison system had become so overcrowded, the treatment of prisoners so god-awful, that a federal court found the state guilty of failing to provide even “the minimal civilized measure of life’s necessities.” The state’s prisons were “bursting at the seams,” in the words of the court, with conditions deteriorating to the point that “a California inmate was dying needlessly every six or seven days.”

In the previous three decades, the number of people locked behind bars in California rose from 25,000 to more than 150,000. But while the prison budget ballooned from just over $600 million to just under $10 billion – from just about 3 percent of the state budget to just over 10 percent – the state had only built enough space to imprison half its actual prisoners. Indeed, some prisons operate at three times their planned capacity. And more than 230 people labeled “severely mentally ill” are currently in solitary confinement not because they broke any rules, but because prison officials say they do not know where else to put them.

One might think the liberal political establishment might be OK with this court-ordered reduction in prison population, what with three-quarters of those in California prisons there for nonviolent offenses – and about one in six for nothing more than drug possession. Newspaper editorials focus on the release of murderers and rapists, but there are plenty of people in prison for petty crimes who should probably be ahead of them in line for release. But when it comes to law and order, the left coast can be more conservative than a red state. Indeed, when the federal court announced its ruling in 2009, then-Attorney General Jerry Brown – now, once again, governor of the state – denounced Washington’s meddling in the state’s internal affairs.

“This order, the latest intrusion by the federal judiciary into California’s prison system, is a blunt instrument that does not recognize the imperatives of public safety, nor the challenges of incarcerating criminals, many of whom are deeply disturbed,” said Brown.

Jerry Brown’s Hammer

As he made clear in a 2008 debate on the program “Democracy Now!,” the only blunt instrument Brown believes in is the iron fist (and iron bars) of the state. Discussing a ballot proposal that would have diverted more nonviolent drug offenders away from prison and into treatment programs – another presumed liberal no-brainer – Brown argued that, contra the advice of public health experts, when it comes to drug addiction “you need accountability, short stays in jail, particularly.” Treatment alone will “leave these unfortunate people mired in their addiction,” said not-a-doctor Brown. “Some of them need the hammer of a drug court.”

As governor, Brown has done his damnedest to make sure the state continues to be the top incarcerator in the world’s leading jailer, the United States, to the point of almost being found in contempt of the federal courts for failing to reduce the state’s prison population as ordered. Indeed, the state Corrections Department announced in October that it was imprisoning 500 more souls than the year before.

Over the summer, Brown revealed a plan to spend what could end up being the bulk of the state’s $1 billion emergency reserve fund – money that is supposed to be spent in the event of an emergency – to finance the transfer of people from California’s overcrowded detention facilities into privately run prisons. “Brown said the alternative is to allow 10,000 prison inmates to go free.”

“It’s going to take some money, make no doubt about it,” Brown said of defying the federal government. But, “Public safety is the priority and we’ll take care of it,” he said, “the money is there.” The estimated cost of transferring the prisoners is about equal to what the state cut in funding for the University of California system between 2008 and 2012.

Of course, there are a lot of things California could do with that money, besides funding prisons (or schools). The state could use its emergency fund to address an emergency, for instance.

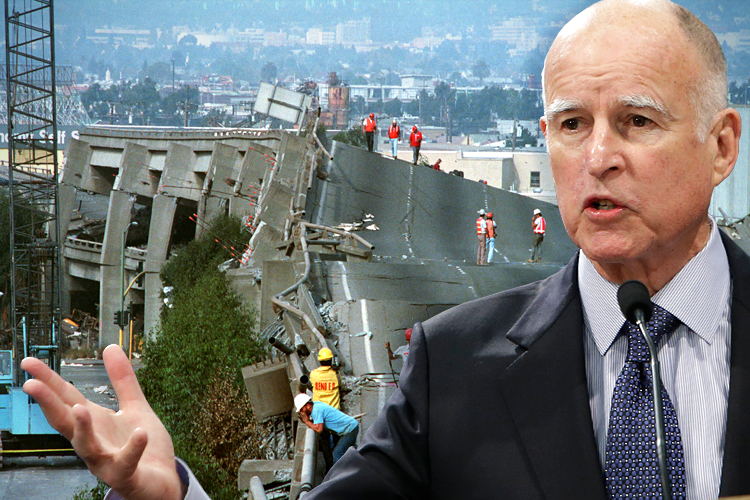

“More than 1,000 old concrete buildings in Los Angeles and hundreds more throughout the county may be at risk of collapsing in a major earthquake,” the Los Angeles Times reported this fall. City officials estimate there are actually 10,000 concrete buildings at risk of collapse. But no one’s talking as if it is an emergency; as if, like the transfer of nonviolent prisoners to for-profit prisons, it is worthy of money from the state’s emergency fund. The next quake could strike at any time, but there’s no sense of urgency. Instead, the Los Angeles City Council is studying the issue, weighing the use of tax credits and a future statewide bond to pay for retrofits – and not rushing into anything.

Councilman Tom LaBonge “said he would meet with builders and landlords to hear their concerns about requiring the retrofitting of buildings,” reported the Los Angeles Daily News. “He also asked the city to look at requiring a monthly earthquake drill to help keep the public alert to the dangers.”

Too Big to Solve

That thousands may die preventable deaths in the next big earthquake may provoke yawns because it isn’t exactly breaking news. In his 1998 book, “The Ecology of Fear: Los Angeles and the Imagination of Disaster,” historian Mike Davis noted that the concrete buildings across L.A. – often, and even more problematically, housing units stacked precariously over carports, like the one in which I wrote this piece – “are quite simply deathtraps.” In the 1994 Northridge earthquake, they were shown to be “particularly prone to catastrophic failure.”

But concrete buildings are only part of the problem. “The big fish are the high-rise buildings with faulty welds, 100 to 150 of them, exposed after the last quake by seismic engineers, reported on and then forgotten,” Davis told me. And then there are all the buildings in Southern California set right on top active faults. “The problem, in other words, is too expensive not to ignore.”

So ignore it the establishment has, preferring the grandstanding over problems that don’t really exist to solving the ones that do.

To this day, buildings are still being built on top of active faults in California. It’s only illegal to do so if the fault shows up on an official state map – and the state has all but stopped updating its maps. As the Times reported, only 23 have been drawn up in the last three decades and, “Because of budget cuts, none were completed between 2004 and 2011.” The slow pace “affects public safety,” the paper stated, because it means about 2,000 miles of faults remain unmapped, “including some in heavily populated areas of Southern California.”

How many concrete buildings in need of retrofitting are built right on top of active faults? No one in Sacramento seems in much of a rush to figure that out. When it comes to public safety, politicians are more likely to instill fear of the remote chance you will be subject to violent crime, not the probability that a major disaster – partly man-made – is certain to strike in the coming years. Indeed, when it comes to that their attitude is similar to the boss at a garment factory in downtown L.A. that makes clothes for the chain Forever 21 who, when told his concrete building was at risk of catastrophic collapse, responded: “Earthquake? Earthquake? Building destroyed? Destroyed. What can I do? It’s natural. If I die, I die.”

Prioritizing Fear

Unlike an earthquake, there’s nothing much to fear from the release of 10,000 prisoners. Indeed, that’s about the number released from California’s prisons every month, even before the court-ordered reduction in population (“realignment”). But there has been plenty of fear-mongering.

“The Los Angeles County Probation Department reports realignment has left it watching over more dangerous ex-cons than ever, prompting a tripling of armed officers,” one Southern California paper editorialized in May 2013. Those released include an “accused murderer of four people in Northridge and one of the men accused of kidnapping and sexually assaulting a 10-year-old Northridge girl.”

The thing about anecdotes is that they are anecdotal. Statistics, however, show that 2013 was the 11th consecutive year of falling crime in Los Angeles, which is home to more ex-offenders than any other part of the state. Violent crime fell 12 percent, with the number of murders the lowest since 1966, despite the city now having 1 million more people than it did back then.

A recent report did show an uptick in property crime, such as burglaries and car theft, across the state, which researchers attribute in part to the early release of some prisoners (L.A., however, experienced a 5 percent drop). That’s sort of to be expected when you release people from prison in some cases without so much as a form of ID, much less a chance. It’s also the sort of thing many countries around the world deal with without throwing people into dungeons; without sentencing people to lengthy terms of emotional and physical abuse.

Getting your car stolen sucks, but who needs a car when you’re lying dead in your collapsed concrete apartment. Theft is a nuisance; an earthquake is a matter of life and death. Let’s not abuse the notion of “public safety” by using it to justify the locking up of nonviolent property and drug offenders. Let’s radically redefine “public safety” to mean the ability to live without fear of being crushed to death in one’s home. And let’s use money saved for emergencies to address an actual crisis.