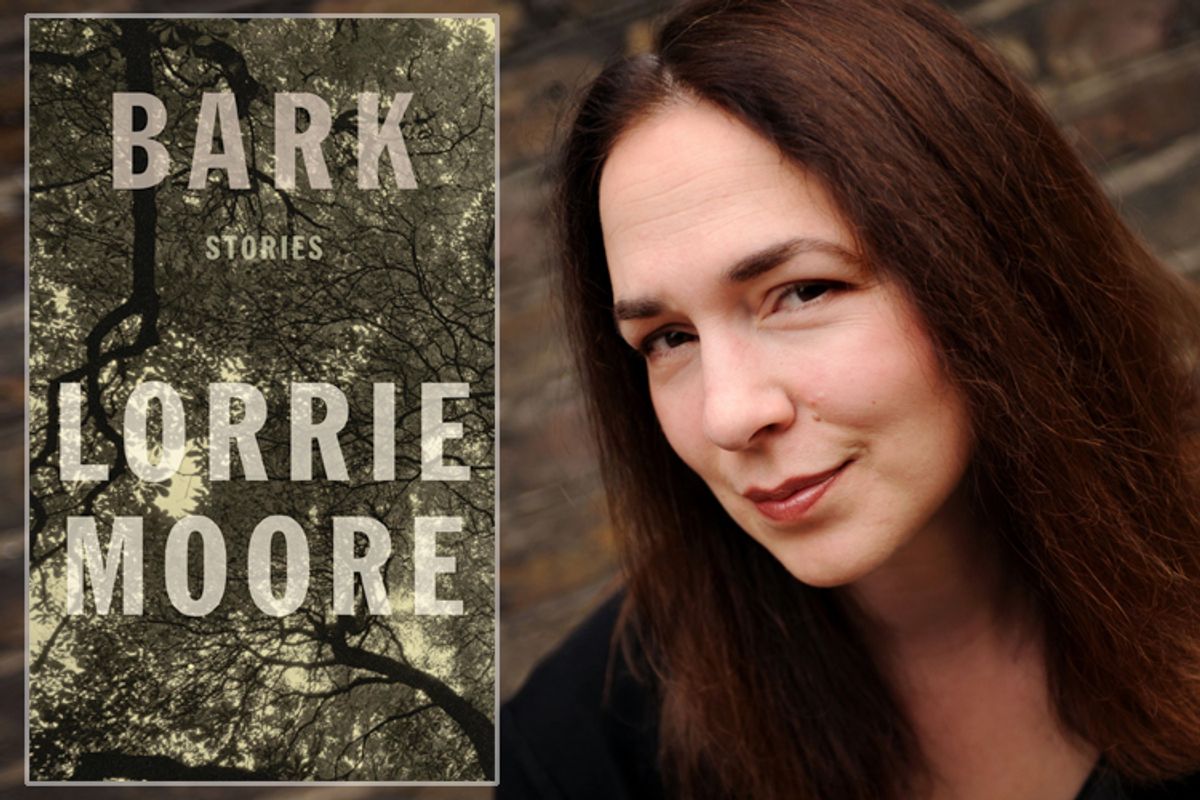

Here are themes and motifs that come up repeatedly in "Bark," Lorrie Moore's fourth collection of stories: a wedding ring stuck on a character's finger after the end of the marriage; the specific taste of meat; dessert being mashed into a human face; suburban streets named in a manner so implausibly twee as to make a resident pensively angry or angrily pensive; preoccupation with the political scene that gives way to a hands-thrown-up sort of exhaustion.

Though "Bark" will, by Moore fans, be compared endlessly to her previous story collections -- not least because it's her first collection since 1998's "Birds of America" -- it bears more similarity to her novel "A Gate at the Stairs," a book that dealt angrily with the state of class and perpetual war in 2000s America. Unlike Moore's earlier collections, "Gate" didn't reward its reader with any sort of lesson or, really, any human warmth; its protagonist, a woman called in to care for the child of a snobbish family, seemed intended to illuminate hard lessons about any number of American crises at the end of empire.

Similarly, the repeated elements in "Bark," as well as an increased attentiveness to politics as background for Moore's stories, add toward a dysfunction that has leached out from the damaged people in Moore's earlier stories into the bloodstream of the entire nation.

"Bark" is political and it is visceral in a manner that may well be jarring for readers accustomed to Moore's past style, which dealt elliptically and aphoristically with traumas in characters' personal lives. The first story, "Debarking," sets the tone, staging a man's attempt to rebuild his life by dating a woman intensely bonded to her son against the run-up to the Iraq War. But the war, here, is dealt with at first in brief references and allusions rather than anything specific; it's only with a name-check of Dick Cheney late in the story that the reader knows with certainty what the war in question even is. It seems more like a work of dystopian fiction than a picture of America in 2003 (when the story was published in the New Yorker); the revelation that the fear of "the war coming home" was a fear we all had and have forgotten or sublimated comes as a shock.

We, as a collective group and a reading public, may be done with the past, but Moore certainly isn't. In "Paper Losses," she introduces a couple who've moved on from love in the nebulously defined "peace movement" toward a rebuke of their past: "Now they wanted to kill each other. They had become, also, a little pro-nuke." There's no such thing as neutrality in Moore's America. One is always at one pole or another, haunted constantly and explicitly with the hazards of modern life. The protagonist of "Debarking" craves "the taste of metal and blood in his mouth" and thinks of his girlfriend's pro-meat bumper sticker floating in a sea of pro- and antiwar messages. Even the desire for sustenance is tied incontrovertibly ("metal and blood"!) to war.

Moore's admirers, of whom I am one, particularly prize her ability to craft a believable world and shared language for her characters. She is unusually good at scene-setting and at creating a milieu in which her characters can allow their thoughts to unfurl and can make jokes. The jokes here are sadder, or aren't really funny at all. Though such things are unquantifiable, there seem in "Bark" to be fewer puns and more cleverly phrased epiphanies, like this one: "She'd been given something perfect -- youth! -- and done imperfect things with it."

Time has passed, for Moore, for her readership, and for the nation, and the collection is at its strongest when it drills down on the creeping strangeness of America's place in history at a given moment or on the strangeness of growing older and -- say -- finding your rings no longer fit. The weakest moments are when the details, political and personal, ring false. In "Foes," for instance, a couple engage in a strange conversation about a promising political candidate alternately called "Brocko" and "Barama" with a woman who was scarred in the attacks on the Pentagon -- a cruel joke on the briefly aroused main character, who first believes that the woman's exoticized looks (actually burn scars all over her face) are "Asian," which draws him in. It's too much for a slight story to bear: the bait-and-switch of this fellow's attraction, as well as the completely ludicrous conversation about Barack Obama, circa 2008. ("Where is his birth certificate?" is uttered.) Some things it is better to leave in the past.

But the dredging up of the birther drama is a consequence of the best element of "Bark" -- that Lorrie Moore is not merely older, having left a few perfect books back in her perfect youth, but angrier. Her characters have always embarked upon doomed affairs, but the sense here is not one of anomic indulgence but of literal last chances. Death haunts the politics and the personal lives of Moore's characters, now. That the timeline of Moore's life so neatly coincided with her aging into a period of national destruction and uncertainty is one of the only things about the 2000s about which we can feel glad. She's left childish things behind, and though "Bark" is sometimes hard to take, it's also a book to which people will refer back to understand life as we lived it in the past 10 years.

Shares