Former President George W. Bush's first public art exhibit, "The Art of Leadership: A President’s Personal Diplomacy," opened at his presidential library in Dallas on Saturday. The left largely greeted his never-before-seen portraits of world leaders with a mix of derision and fascination.

It would be easy to merely rag on these paintings. Of course they're terrible; Bush is an amateur painter, and very literal-minded. Commentators have compared the works to coloring-book images and kitsch. Those are fair enough descriptions. But when you take the pictures on their own terms, they also reveal something more interesting about the former president.

Bush has painted caricatures, intended to exaggerate the leaders' personalities, not necessarily represent their likenesses. He's not trying to match the impressionist masters, whose portraits -- such as Renoir's of his son in a sailor suit -- draw attention to the exquisite details of their subjects' expressive eyes and mouths. Dubya freely admits his paintings aren't especially good.

Bush has painted caricatures, intended to exaggerate the leaders' personalities, not necessarily represent their likenesses. He's not trying to match the impressionist masters, whose portraits -- such as Renoir's of his son in a sailor suit -- draw attention to the exquisite details of their subjects' expressive eyes and mouths. Dubya freely admits his paintings aren't especially good.

They're bad partly because he sees the leaders as a child would. He's incapable, emotionally and technically, of finely observing them and conveying what they're like independent of his own objectifications. He engages them without subtlety. In these paintings, he's saying, "This guy's got a super-neat hat!" (Afghanistan's Hamid Karzai); "this lady is strong!" (Liberia's Ellen Johnson Sirleaf); and so on.

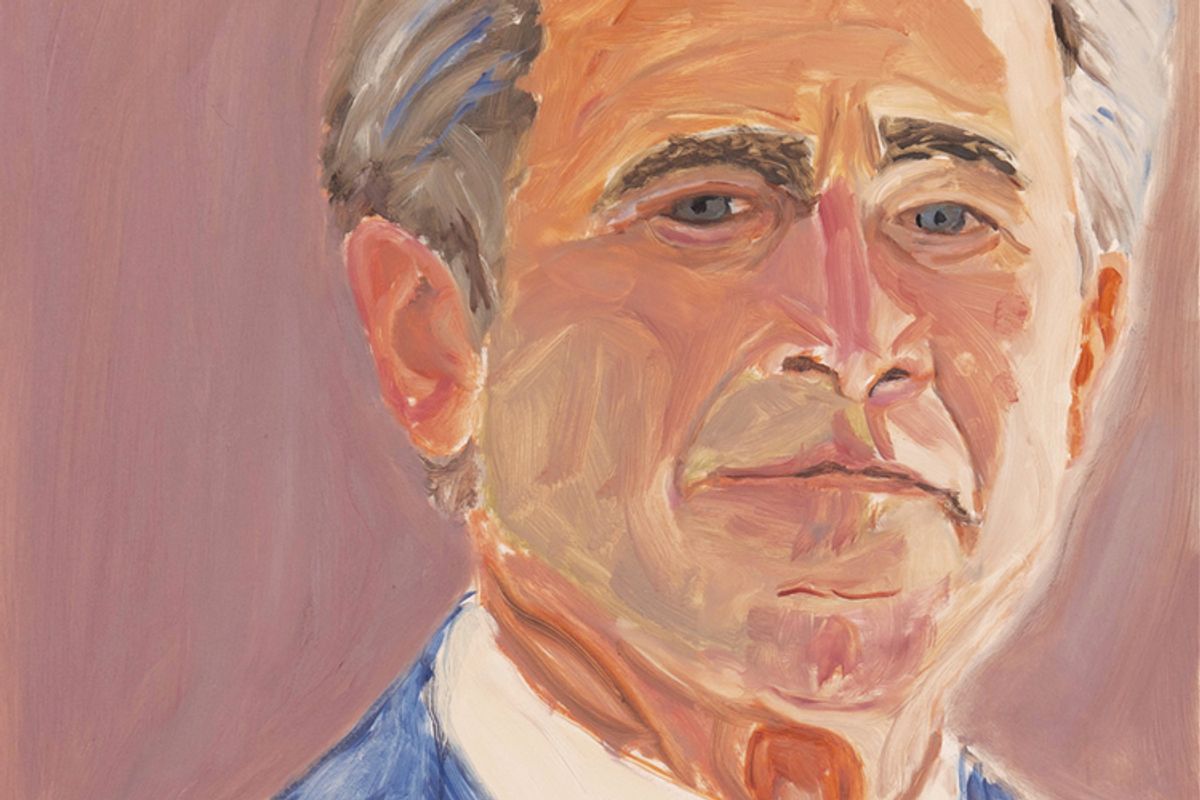

The first painting in the exhibit is Dubya's self-portrait. It's a quick, rough work, with little blending and an obligatory feel to it. The set of his chin is a proud one, but what's surprising are the eyes. There's some self-pity going on here, some sadness.

In office, he swaggered about, telling the planet that he and the U.S. were in the right. His administration, as journalist Jeremy Scahill documents in "Dirty Wars," turned the world into his battlefield. Now he's at home, away from it all, wondering what it meant, and painting other world leaders to show he's one of them, someone who mattered, despite his record-low approval rating upon leaving office.

Indeed, that's the whole idea of a presidential library: legacy. The building is Bush's pyramid, his Giza. Citizens are to make pilgrimages to see the sacred objects he touched — the bullhorn from ground zero and his cowboy boots, for example. Professional archivists tending to his millions of documents are civic religion priests. As art historian Benjamin Hufbauer explains in his excellent book "Presidential Temples: How Memorials and Libraries Shape Public Memory," a presidential library serves as the base of its namesake's final campaign — to be worthy of veneration in the eyes of posterity.

That's why the exhibit designers and docents use Pentagon-esque "perception management" on the audience, like campaign communications staff or information warfare operators. A folksy video on the entry room's screens beat the audience over the head with the point that the paintings expressed Bush's personal relationships with the leaders. In the first proper room of the exhibit, a docent lectured the audience loudly: "The portraits' backgrounds don't mean anything. Kind of be aware of that. Green doesn't mean anything—it's just green. Red isn't angry, blue isn't sad." The spiels might make some sense given that the setting is a museum, not an art gallery, but this is education as propaganda. When the library opened, Bush told the Dallas Morning News the library would explain his decisions without "finger-pointing" or "sorting it out for people."

The second portrait is Dubya's father, George H.W. Bush. The son said he painted "a gentle soul." People seem to forget "Poppy" was a CIA director before his presidency. In the portrait, his head takes up most of the frame, making him an imposing figure. Despite his rosy cheeks, he stares at the viewer with a hard, judging gaze. Poppy, whose intelligence Dubya seems to have feared, must have pushed his son down the path of the dynasty he had prepared for him. Quotes from Dubya throughout the exhibit stressed that he modeled his personal diplomacy on his father's behavior. It all suggests the son is still very much seeking Poppy's approval.

The second portrait is Dubya's father, George H.W. Bush. The son said he painted "a gentle soul." People seem to forget "Poppy" was a CIA director before his presidency. In the portrait, his head takes up most of the frame, making him an imposing figure. Despite his rosy cheeks, he stares at the viewer with a hard, judging gaze. Poppy, whose intelligence Dubya seems to have feared, must have pushed his son down the path of the dynasty he had prepared for him. Quotes from Dubya throughout the exhibit stressed that he modeled his personal diplomacy on his father's behavior. It all suggests the son is still very much seeking Poppy's approval.

Former British Prime Minister Tony Blair is the first foreign leader in the exhibit. These world leaders, even out of office, don't have time to sit down and pose, which is why Bush painted from photographs, not an uncommon practice for visual artists, contrary to much of the commentary in the media. Of the 30 paintings, it seems Bush spent the most time on this one. The blending here is more careful, the eyes more detailed, than in his other works. The others typically emphasize headdress and jewelry, but the attention here is focused on Blair's strong, thoughtful face. Bush wants his friend to be seen positively. "I've heard he's been called 'Bush's poodle,'" Dubya once said. "He's bigger than that." Bush needed and appreciated Blair's support for his invasions and war on terror — even, presumably, for the CIA's torture, kidnappingsand black sites, all of which Blair knew about in detail.

What Bush did in office sickens the stomach, but there's no hint of those horrors as you walk through the exhibit. In almost all the photographs that accompany the paintings, Bush is laughing and joking with his now-subjects. That's what he likes to do: laugh and joke. He sees these leaders as his club mates. That's a little startling after his black-and-white bombast in office — "you are either with us or against us," he infamously told the world — but same as just about any politician, Bush wants to be liked.

He is, however, on less friendly terms with Vladmir Putin, apparently. His dour portrait of the wily Russian president shows a long-faced, thin-lipped man who can't take the artist's jokes and who looks at the audience like they're wasting his time. Most of the others show the artist's affection for his subjects.

He is, however, on less friendly terms with Vladmir Putin, apparently. His dour portrait of the wily Russian president shows a long-faced, thin-lipped man who can't take the artist's jokes and who looks at the audience like they're wasting his time. Most of the others show the artist's affection for his subjects.

Nuke-armed Putin, recently in the news for taking Crimea, has his own creepy back story, including close proximity to the false-flag bombings in Moscow that he used as a pretext to invade Chechnya. The portrait is fittingly unsettling. Also unsettling is that Putin is painting too; at a charity auction in St. Petersburg, his "A Pattern on a Hoarfrost-Encrusted Window" fetched 37 million rubles.

In contrast, Bush's portrait of the 14th Dalai Lama indicates that while the two men couldn't have agreed on, say, human rights versus military aggression, they still have respect for one another. When they met, they must have put politics aside and enjoyed each other as humans beings, something Dubya seems to have wanted to do with all of the leaders he painted. "I love him," the Dalai Lama said. "Really. Very nice person, on a human level." Bush took time with the furrows of the holy man's brow and the smile lines of his cheeks, characterizing him as a wise sage — although that's putting it a little generously when it looks more like Bush is saying, "Check out his cool robes!" Throughout the exhibit, Bush is fascinated by official dress of station; as if, meeting the leaders in person, he complimented their clothes to break the ice—while wishing he too were afforded more opportunities to wear a cool costume in office.

The last leader in the exhibit is former Mexican President Felipe Calderón. Bush, having gotten something of a handle on shading and blending here, shows him as a polished, well-groomed man with neat hair and smooth skin. Calderón's pensive face is centered in the frame. The serious portrait suggests not an emotional bond, but that the Mexican leader was important to Bush in a strategic way. Indeed, Calderón gave the U.S. unprecedented cooperation in security matters, allowing the superpower to fuel his war against drug cartels. Within a few years of Calderón's opening that door, a "shit-ton" of undercover American operatives entered the country -- in the words of Mexican diplomat Fernando de la Mora Salcedo in a memo published by WikiLeaks.

You have to wonder how, living in a world where cloak-and-dagger intelligence operations and life-and-death decisions are routine, these leaders can find, in something like painting, not just refuge, but also, in Bush's case, joy. Dwight Eisenhower, Winston Churchill, Jimmy Carter and others painted after office. Fear of assassination or, in Bush's case, fear of arrest for war crimes if he travels overseas, must alter your perceptions of life. These men may not be as simple as radicals on either side like to imagine. Bush, you have to remember, was groomed all his life for a world where black ops and apple pie go together. That is why his paintings seem so surreal to the rest of us.

Douglas Lucas is a writer and journalist in Fort Worth, Texas. His articles have appeared in Vice, WhoWhatWhy, Nerve, and other venues. Email him at dal@riseup.net or follow him on Twitter: @DouglasLucas.

Amy O'Neal is a visual artist and costume designer in Fort Worth, Texas.

Shares