In recent years, many people have been talking about Literary Citizenship. “Are you a good literary citizen?” Roxane Gay has asked on the AWP blog. In a 2011 interview with Jonathan Lethem, David Kipen describes the author as a “model literary citizen.” On her blog, Charlotte Morganti writes, “Creative writing and the literary world would be in a fix without…literary citizens.” On Beyond the Margins Bethanne Patrick recently posted “Being a Good Literary Citizen: a Manifesto.” And at Ball State University, Cathy Day has taught a workshop entirely devoted to Literary Citizenship, yielding numerous blog posts and articles on the subject.

Specific advice differs from one person to another, but most agree that good Literary Citizenship entails buying from local bookstores, attending readings, subscribing to literary magazines, interviewing writers, reviewing books, reading a friend’s manuscript, blurbing books, and so on.

I agree with the value in all of these activities. Yes, by all means, if you want to build a literary career, you’ve got to form professional networks in your field. You’ve also got to support the small presses, bookstores, literary magazines and libraries in which you hope to see your own work showcased. This is so obvious that it’s surprising it has to be mentioned at all. But it does have to be mentioned, and those who write the blogs and manifestoes of advice are good to do so.

What I think is missing from this narrative about Literary Citizenship, however, is an origin story. Why do writers need to do these things? In what context are these activities so necessary?

To understand the rise of the Literary Citizen, perhaps first we need to look at the meltdown of our economy.

In 2009, Chris Artis wrote in Publishing Perspectives, “With the recent economic downturn, book advertising — in the traditional sense at least — is on the decline. The majority of US publishers have cut their marketing budgets by 50-70 percent over the last year.” Echoing that idea in the Huffington Post, Jenny Darroch reported that “advertising expenditure in the U.S. fell 15.4 percent in the first half of 2009.” Adds Darroch, “In times of recession, marketing budgets are…the first to be cut.”

Who, then, must make up for this shortfall? Certainly it’s not the owners and CEO’s of publishing companies who lend a hand to writers in times of duress (in spite of the fact that their profits are derived precisely from those writers). No, it’s writers who are expected to look after themselves and one another.

Wildfire Marketing lays it out quite clearly. Company founder Rob Eagar informs publishers that there is a way to “maximize budgets in tough times.” Namely, “You can train your authors to handle more of the marketing efforts. Writers who become skilled at promoting books can produce thousands of dollars in extra profits for the publisher.”

But wait. It gets better. An added benefit, Eagar writes, is that “these authors don’t require expensive salaries, office space, insurance packages, or retirement plans. Instead, the publisher just pays a small author royalty…It’s a win-win, right?”

Such advice might sound shocking, disturbing or hilariously blunt. The sad truth of the matter is that such views are pervasive in this industry. Today’s writers are expected to do more marketing work than ever before while not expecting much in the way of compensation or benefits. It’s what we are being “trained” to do.

Another effect of the economic crisis is the demise of book reviews in newspapers. In the Columbia Journalism Review, Steve Wasserman writes that in “April [2001], the San Francisco Chronicle folded its book section into its Sunday Datebook of arts and cultural coverage…In 2001, The Boston Globe merged its book review and commentary pages. Today, The New York Times Book Review averages 32 to 36 tabloid pages, a steep decline from the 44 pages it averaged in 1985…whether the book beat should exist at all is now, apparently, a legitimate question.”

With fewer books reviewed in newspapers and magazines, who picks up the slack? Do the owners of media conglomerates step in to review a book here and there? Do the CEO’s of publishing houses get on the blog-wagon and start reviewing the books that help pay their six-figure salaries?

Doubtful.

It is writers, working mostly without pay, reviewing books, interviewing fellow writers, and tweeting and posting messages about books they love and authors they admire on social media.

If I haven’t yet thoroughly depressed you, let’s look now at bookstores. According to the Open Education Database, “Stores like Waldenbooks, B. Dalton, and Crown Books are long gone, but the biggest casualty has been Borders, who [has] closed more than 600 stores after filing for bankruptcy…Things aren’t looking good for [Barnes and Noble], even with a solid digital investment…” The site also reports that “The number of independent bookstores dropped from 2,400 to 1,900 between 2002 and 2011.”

Here is where writers must enter the picture not just as scribes and marketing mavens but also as avid and socially-conscious consumers. Writers, we hear often, must work to keep brick and mortar bookstores alive. As Bethanne Patrick writes in her Literary Citizenship manifesto, “If we don’t attend each others’ readings and buy each others’ books, who will?” Here at Beyond the Margins, it was Nichole Bernier, a novelist and nonfiction writer, who worked hard to organize and promote the 2012 “Saving Bookstores: Desperate Indie Measures Campaign.”

Here too, the burden to ameliorate the negative effects of these industry changes falls not upon those responsible for said changes, but upon writers.

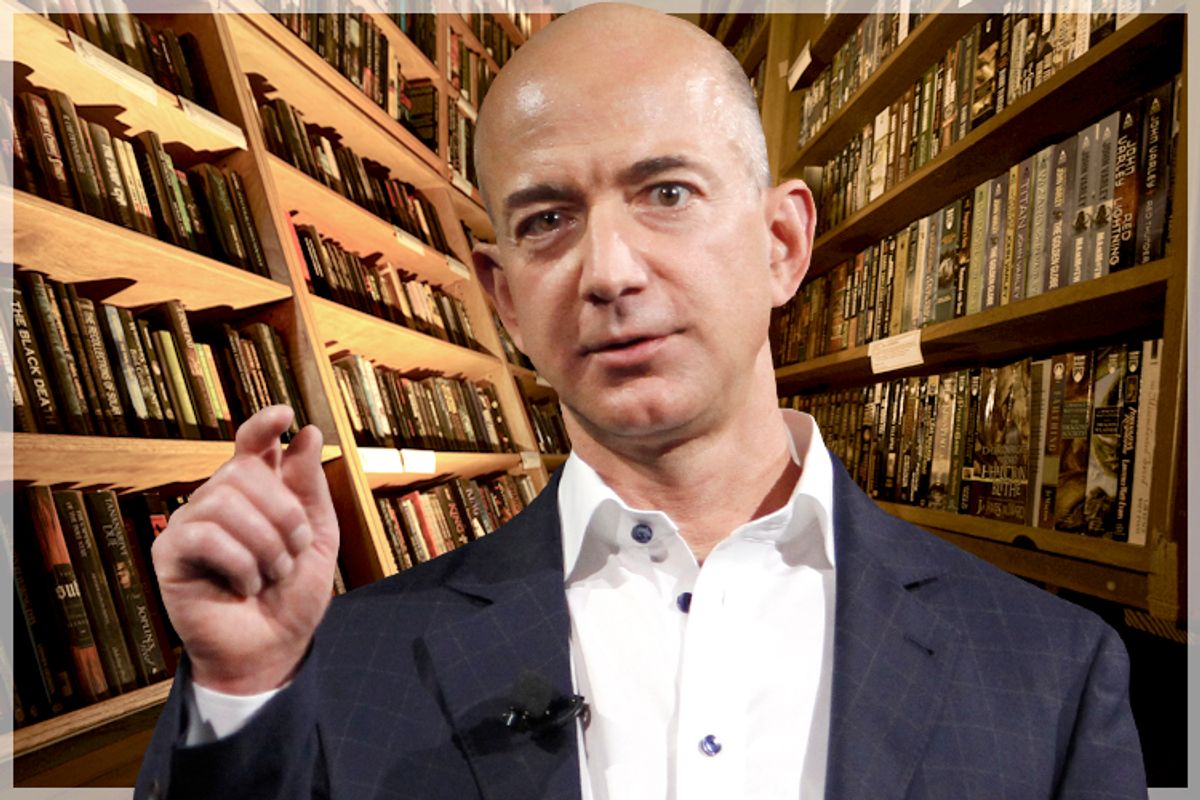

Other factors have contributed to industry changes, of course. The rise in digital publishing is one. Amazon is another. The surge of social media outlets, many of which are aimed specifically at the book industry (Goodreads, Shelfari, etc.) is still another. But the end result of all these changes is the same: more and more work is getting sloughed off to writers who earn “the smallest piece of the pie.”

It is here where I must make a confession: I really detest the phrase “Literary Citizenship.”

By evoking such positive qualities as citizenship and community-mindedness, the message behind Literary Citizenship seems to be that writers should embrace this new dawn. We should accept it, perhaps even celebrate it. In doing more work (editing manuscripts, reviewing books, interviewing writers, blogging about writing, sharing news about books, etc.) for less pay, we will become good citizens.

In fact, companies have long employed these kinds of tactics, namely spinning poor working conditions into “enrichment opportunities” for workers. In his 1991 book "Culture, Inc.", media critic and sociologist Herbert Schiller writes about these strategies to silence dissent among workers.

Schiller quotes from a 1980s Wall Street Journal article: “Corporate America has started one of the most concerted efforts ever to change the attitudes and values of workers. Dozens of U.S. companies…are spending billions of dollars on so-called New Age workshops. The training is designed to foster such feelings as team-work, team spirit, and self-esteem….Most of the programs share a common, simple goal: to increase productivity by converting worker apathy into corporate allegiance.”

Of course, I am not suggesting that those who have written about Literary Citizenship are trying to silence dissent or advocate sheepish adherence to the status quo. On the contrary, I believe these folks are genuinely trying to help writers get a foothold in constantly shifting and unpredictable terrain.

It’s just that in all this talk about what makes a good Literary Citizen, it seems we have missed a key step: critical reflection. Isn’t it important to ask why things are the way they are? The notion that the system ought to be challenged, that there is even a system within which all this is operating, is notably absent from discussions about being a good Literary Citizen.

Isn’t it time we asked what we actually mean when we talk about helping our fellow writers? In what ways can writers’ lives be improved on an institutional level?

The formation of writer unions, strikes organized by writers, new avenues in cooperative publishing (a “‘Hegelian solution’ for many authors”), magazines like the new Scratch, which focus exclusively on issues related to writing and money, Occupy movements specific to the cultural realm such as Occupy Museums, and other forms of resistance, provocation, or simply frank discussions about labor power and financial remuneration seem to me what is really called for here.

Certainly, I do not have all the answers. But a deeper look at the economic structure that informs the way writers work today seems to be a logical starting point.

Shares