We are all Wile E. Coyote now, and we’ve just looked down. No one can say, exactly, when we ran off the cliff of irreversible man-made climate change. But we’ve been running on air for quite some time — and now it’s over. With two new studies (University of Washington and UC Irvine/NASA) telling us the West Antarctic Ice Sheet is collapsing, we can finally see there’s no ground beneath us. Now we begin to fall.

According to the press release from NASA:

A new study finds a rapidly melting section of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet appears to be in an irreversible state of decline, with nothing to stop the glaciers in this area from melting into the sea. The study presents multiple lines of evidence, incorporating 40 years of observations that indicate the glaciers in the Amundsen Sea sector of West Antarctica “have passed the point of no return,” according to the lead author.

And UW reported:

Models using detailed topographic maps show that the collapse of the West Antarctic ice sheet has begun….

University of Washington researchers used detailed topography maps and computer modeling to show that the collapse appears to have already begun. The fast-moving Thwaites Glacier will likely disappear in a matter of centuries, researchers say, raising sea level by nearly 2 feet. That glacier also acts as a linchpin on the rest of the ice sheet, which contains enough ice to cause another 10 to 13 feet (3 to 4 meters) of global sea level rise….

The good news is that while the word “collapse” implies a sudden change, the fastest scenario is 200 years, and the longest is more than 1,000 years. The bad news is that such a collapse may be inevitable.

The studies are stunning in their specificity and projected impacts. As Sarah Gray noted here on Wednesday, the impacts on New York, New Orleans, Miami and other coastal cities are expected to be enormous, forcing hundreds of thousands of residents to move. Miami’s porous limestone foundations and lack of higher ground make its future particularly perilous.

The only possible silver lining here is if the story changes us — changes how we think and how we act, so that it is finally commensurate to the threat that our way of life has created.

Although stunning in their specificity, none of what these two studies show was unexpected. In a 1968 paper, glaciologist John Mercer called the West Antarctic Ice Sheet a “uniquely vulnerable and unstable body of ice,” according to a NASA background webpage. Five years later, University of Maine researcher Terry Hughes posed a question in the title of his paper, “Is the West Antarctic Ice Sheet Disintegrating?” And five years after that — 1978 — Mercer published “West Antarctic ice sheet and CO2 greenhouse effect: a threat of disaster.” The title alone should be enough to silence the canard that scientists in 1970s thought the Earth was cooling.

In the paper, Mercer noted that there had been testimony before the U.S. House of Representatives that burning existing fossil fuel reserves would increase atmospheric CO2 to five to eight times that of preindustrial levels, resulting in almost certain “climatic disaster.” But the potential melting of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet meant a mere doubling of atmospheric CO2, which within 50 years could spell catastrophe.

Given this early history and decades of other research since, fleshing out the threat though not nailing it down specifically, my initial reaction was to think of how greater uncertainty had suddenly turned into a recognized greater threat, despite the fact that previously the uncertainty had clouded the perception of threat. This was precisely the point of two recent papers by Stephan Lewandowsky, which I discussed as part of my recent Salon story on his work. So I reached out to Lewandowsky for comment, telling him that the studies struck me as an example of the sort of increased threat we can’t be certain of, but must take account of, the greater the uncertainty we face. I began by asking how his reaction squared with mine.

“My reaction was ‘Gee, surprise, surprise…’” Lewandowsky responded by email. “This is precisely the kind of discovery that I would expect to see more of in the future, given the large uncertainty. So your impression is spot-on.”

I then asked Lewandowsky about the main sorts of uncertainty he could foresee that we should be concerned about. “In general, any positive (amplifying) feedback loop must be of concern,” he replied, “There are several that we know of (e.g., reduced albedo from melting ice, release of methane in tundra, that sort of thing).”

I then went on to ask him what else we should be thinking of with respect to projected sea-level rise. “I think we need to think beyond the century,” he said. “Too much climate discussion has a horizon of 2100, which seems like a long time away to us, although babies born today are quite likely to still be around then (given expected increases in life expectancy). We seem to pretend that there won’t be anyone around to worry in 2200 or 2300, but I suspect people then will be as affected by natural catastrophes and the disappearance of Bangladesh as we would be today.”

On his suggestion, I also reached out to Pennsylvania State University geologist Richard Alley, author of more than 170 scientific papers about global warming and Earth’s frozen regions, as well as several books, including “The Two-Mile Time Machine: Ice Cores, Abrupt Climate Change, and Our Future,” which includes his co-discovery that the last ice age came to an abrupt end in just three years. His deep experience in the field, his long-term perspective and his sensitivity to abrupt events were enough to recommend him individually. Combined, they made him the ideal climate scientist to seek more insight from.

“The new results are consistent with what we know about the past,” Alley told Salon. “First, the Antarctic ice sheet was bigger during the last ice age, and as it shrank, it left a record on the seafloor. That record indicates that the ice would sit somewhere, changing little, for a long time, and then rapidly jump back to a new point of stability. The new modeling suggests that we are close to, and perhaps already committed to, the next rapid retreat.”

“The record of sea-level changes in the past is not perfect, but indicates that there were times when sea levels rose notably faster than the recent rise we have been experiencing,” Alley continued. “We do not have any proof that the West Antarctic Ice Sheet was involved in these rapid changes, but the available evidence points rather strongly to loss and regrowth of the ice sheet in the geologically recent past. So, the new work fits well with what we have learned about the past.”

I then asked about potential threats of abrupt climate change that are (or might be) significantly more likely as a result of this news. Alley began setting up his response by calling attention to a 2013 report from The National Academy of Sciences/National Research Council,”Abrupt Impacts of Climate Change: Anticipating Surprises.” In its preface, it says:

“A study of Earth’s climate history suggests the inevitability of “tipping points” — thresholds beyond which major and rapid changes occur when crossed — that lead to abrupt changes in the climate system. The history of climate on the planet — as read in archives such as tree rings, ocean sediments, and ice cores — is punctuated with large changes that occurred rapidly, over the course of decades to as little as a few years. There are many potential tipping points in nature, as described in this report, and many more that we humans create in our own systems.”

“The possible rapid shrinkage of West Antarctic ice was prominent in that report,” Alley continued. “It noted that some worries (an abrupt change in North Atlantic circulation, a very rapid release in methane gas from the seafloor or the tundra) are considered quite unlikely based on the full record of research. Concerns remain about expansion of oceanic ‘dead zones,’ possible loss of key ecosystems such as the Amazonian rainforest, and abrupt changes in our economies,” Alley said. “The new research especially addresses the issue of sea-level rise, confirming that the West Antarctic Ice Sheet is still moving in the direction of a relatively abrupt rise, and showing via modeling that ‘the fuse may already be lit’ for such a change, without specifying exactly when or how rapidly.”

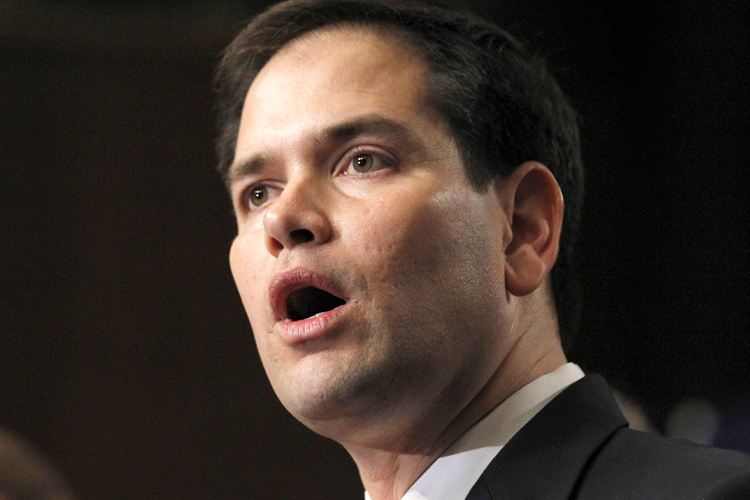

The vulnerability of economies as an ecological consequence is particularly ironic, given denial-minded politicians’ reflexive rejection of climate change mitigation as economically harmful. We saw that again just this week with Marco Rubio’s statement that “I do not believe that human activity is causing these dramatic changes to our climate the way these scientists are portraying it. And I do not believe that the laws that they propose we pass will do anything about it. Except it will destroy our economy.”

But a recently announced forthcoming study presents a compelling example of the exact opposite sort of causal relationship — precisely what the National Academy of Sciences was warning about. A preview story at Phys.org, “Climate change caused empire’s fall, tree rings reveal” explains how climate change actually ravaged several different civilizations around the same time. “A major short-term arid event … had major political implications. There was just enough change in the climate to upset food resources and other infrastructure, which is likely what led to the collapse of the Akkadian Empire and affected the Old Kingdom of Egypt and a number of other civilizations,” the story said, according to the lead researcher, archaeologist Sturt Manning. That change was apparently relatively minor compared to what lies ahead for us.

Given the attention these studies gave grabbed, the question naturally arises, “What else aren’t we paying enough attention to?” I asked Alley what his answer would be.

“Even if the recent changes have committed us to the loss of much of West Antarctica’s ice, we are fairly confident that we have not crossed the threshold for survival of the ice on Greenland and East Antarctica, but that too much warming would commit us to still more sea-level rise,” he said. (However, as Linday Abrams reported here earlier this month, “A new study in the journal Nature Climate Change highlights the risk posed by a region of the East Antarctica that, it turns out, is a lot more vulnerable to global warming than previously thought.”)

“We have much to learn about the effects of ocean acidification, and the effects of rising temperatures and other issues including human fertilizer on oxygen and ‘dead zones’ in the oceans,” Alley continued. “Ecosystems and economies are important but imperfectly understood. So, there are plenty of questions waiting to be answered, and the answers may be very important.”

Finally, I asked Alley, what we should be doing that we aren’t doing already — including thinking differently?

“There are many recommendations in the National Academy report, which may be of interest,” he prefaced his response. “If you take the projected climate changes under business-as-usual, and ask about the economic implications of the impacts, strong scholarship shows that we will be better off if our planning uses the science in decision-making, to move us towards a sustainable energy system.”

Indeed, a new report from the International Energy Agency, “Energy Technology Perspectives 2014,” finds that cost savings in energy will far exceed the cost of investments to rapidly shift away from carbon-based energy. As the press release for the report explains:

The report finds that an additional USD 44 trillion in investment is needed to secure a clean-energy future by 2050, but this represents only a small portion of global GDP and is offset by over USD 115 trillion in fuel savings. The new estimate compares to USD 36 trillion in the previous ETP analysis, and the increase partly shows something the IEA has said for some time: the longer we wait, the more expensive it becomes to transform our energy system.

Reflecting a more cautious stance, Alley continued, “The uncertainties are such that the costs of the changing climate may be a little less than typically estimated, or a little more, or a lot more — too much warming could raise sea level greatly, with very large costs. So, what we don’t know about the future of climate change tends to recommend more action now to slow down warming if we wish to be economically optimal, not less.”

This returns us again to questions of uncertainty and threat. I asked Lewandowsky what other threats we ought to be concerned about, clouded by varying degrees of uncertainty.

“I personally would worry about fire (a lot), drought (less so), and floods (a lot),” he began. “The reason for this is that there is an increasing trend in weather conditions that are conducive to wildfires (e.g., in Australia), and so sooner or later this risk will translate into actual fires. Likewise, we know that precipitation events are on the increase, and so we will get more (and worse) flash floods that are unconnected to sea levels. We know that those events will become more frequent even if we don’t know where and when they will occur — so yet again, uncertainty is not (y)our friend.”

In sum, we now know that a major climate impact is coming, which will cause massive population relocation at the very least. The time frame is still quite broad, but the impact is surely coming. So the question before us remains, How will we respond? How will we avoid making matters worse? And how will we do it equitably, as well?

“The choice is to balance between suffering, mitigation, and adaptation. We can no longer avoid the suffering, but we can still mitigate to reduce the inevitable, and anything that’s left we might be able to adapt to,” Lewandowsky responded.

“However, we must be very careful that we specify what ‘adaptation’ means,” he cautioned. “Sure, building a dike is adaptation and a good idea (though costly). However, ‘adaptation’ can also mean that we will evacuate Bangladesh (or let its population drown), and those things aren’t exactly cheap or even doable. So my take is that ‘adaptation’ is a catch-all phrase that has become way too attractive because it includes a basket of very unpleasant and expensive or impossible measures. So we must be very careful to state precisely what we mean by ‘adaptation’ and we must define a range of ‘adaptability’. We will not ‘adapt’ to 4C warming in the same way we will not ‘adapt’ to living in a pit full of rattlesnakes.”

If Lewandowsky’s warning still seems too long-range for you, then consider the climate impacts already under way, including the climate contributions as part of the mix in the recent crisis in lime prices, as explained earlier this week here at Salon. And then consider this, from the story about the collapse of the Akkadian Empire:

“The tree rings show the kind of rapid climate change that we and policymakers fear,” says Manning. “This record shows that climate change doesn’t have to be as catastrophic as an Ice Age to wreak havoc. We’re in exactly the same situation as the Akkadians: If something suddenly undid the standard food production model in large areas of the U.S. it would be a disaster.”

In short, we don’t have to worry about something worse happening than the collapse of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet. Something much less drastic could prove catastrophic as well.