According to a new Pew Research Center report, by the time 2025 rolls around the Internet of Things will dramatically improve our lives. Janna Anderson, co-author of the document, says experts expect “positive change in health, transportation, shopping, industrial production and the environment.” While these are genuine possibilities, I’m worried that insufficient attention is being paid to a troubling issue that goes beyond potential privacy problems: the moral cost of outsourcing our decisions to increasingly interconnected smart devices.

Consider our daily doings once the Internet of Things goes mainstream. The contributors to the report envision we’ll be surrounded by stuff that’s livelier than the magic brooms found in Walt Disney’s “Fantasia” — milk cartons alerting grocery stores when they’re empty; toothbrushes that communicate directly with dental offices; personalized travel recommendations that integrate our commuting and eating preferences; smart clothing that nudges us to exercise; devices that signal how we want others to treat us; and artificial-intelligence agents who do our personal shopping.

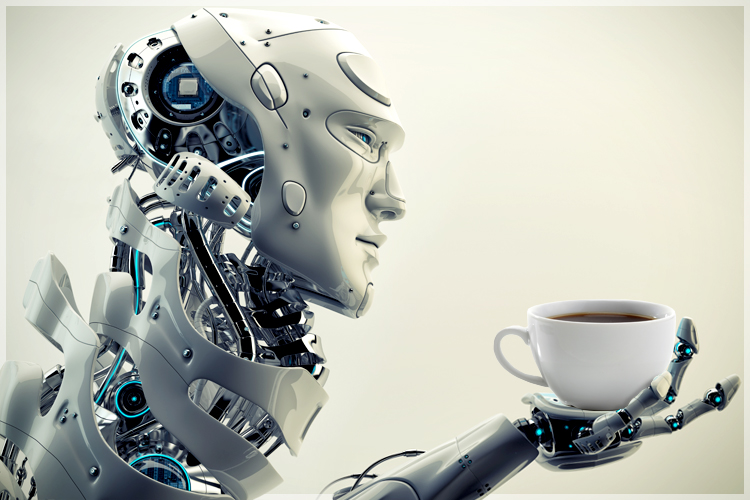

Google surely will be at the forefront of some the most anticipated innovation, and its chief economist, Hal Varian, left his mark on the Pew Center analysis by declaring: “Centuries ago, rich people had servants, and in the future, we will all have cyberservants.” Apparently everywhere we go technological valets will track and assess our behavior, steer us towards goals, and even anticipate our needs. To paraphrase an insurance slogan, like a good neighbor the Internet of Things is there.

At first blush, it sounds great to get digital Jiminy Crickets. They’ll work tirelessly on our behalf. And, they can’t be exploited like human servants who have feelings and belong to social classes. But before toasting to a future filled with guilt-free flunkies, we should consider a skeptic’s words of caution.

Aaron Balick, author of “The Psychodynamics of Social Networking,” put his finger on the key issue of outsourced labor when he told the Pew researchers: “Positive things may be tempered by a growing reliance on outsourcing to technologies that make decisions not based on human concerns, but instead on algorithms…We may begin to lose sight of our own desires or our own wills, like many of these drivers who we hear about who, because their GPS told them to, end up in the most unlikely places in the face of all sorts of real-world, contrary evidence.”

Balick is right to be concerned about autonomy diminishing when chronic computational coaching choreographs our comings and goings. But there’s also a related existential problem to be on the look out for, a matter of alienation that has profound consequences for whether we’ll find our projects and relationships meaningful. Welcome to deceptive delegation.

When we delegate life’s hard work to ubiquitous behavior-directing technologies that fade in the background, two intimately related things happen. We become disconnected from decision-making. And, we become susceptible to believing we deserve credit for the devices acting on our behalf doing a good job.

Deceptive delegation is a prominent feature of sociological depictions of our current relationships with human assistants. Indeed, when Arlie Russell Hochschild conveys the emotional duplicity at stake in working with a wedding planner, she might as well be discussing why the Internet of Things is setting us on a collision course for widespread disingenuousness.

Hochschild’s “The Outsourced Self: What Happens When We Pay Others To Live Our Lives For Us” examines the increasing number of tasks the contemporary market allows us to delegate to hired help, consultants, and surrogates. She devotes a chapter to wedding planners because their job exemplifies the complications of outsourcing. On the one hand, they are tasked with providing clients with customized experiences that make the big day special. To do this, a wedding planner needs to learn the essence of a customer’s tastes and preferences and create events that reflect unique personalities. On the other hand, wedding planners effectively need to disown some of their Herculean effort. Transferring a sense of accomplishment enables the bride and groom to take ownership of the ritual and remain emotionally attached to its organization and execution.

“So part of the hired specialist’s job was to take over an emotional attachment to an act—to become anxious if the gold framed lemon tree cards were not to the left of each dinner plate, to feel relief noting that they were,” Hochschild explains. “And part of her job was to give that emotional attachment back, so that Laura and Trevor [i.e., the engaged couple] could feel involved as if they had set the cards themselves.”

True, this example speaks to an instance of outsourcing that only affluent couples can afford. Still, the type of experience that Hochschild describes can be generalized. It’s an issue we all face every time someone or something acts on our behalf and we’re given credit or blame for the results. (Think of the rationalizing manager who gets criticized by corporate because his personally selected sales team isn’t meeting its quota. Rather than acknowledging the bitter reality that the company is pushing goods consumers don’t want, he pushes the blame downstream –focusing on how others approach pitching and acting as if things would be different, if he were the one making the calls.)

When blame is involved, many find it awfully tempting to scapegoat the proxy and create distance from the immediate cause of the disaster, perhaps proclaiming that if we were more directly involved things would have done better. But truth be told, the seduction of bad faith remains powerful when good results are at issue, too.

When we receive praise, it’s hard not to take credit for what’s being acknowledged. If future you gets accolades for meeting exercise and dietary goals, is your distant self really going to share the kudos with the smart navigation device that steered you away from fast food restaurants and the smart workout gear that boosted your digital willpower? If not, don’t worry about being outed as a credit hog. Because the tools making up the Internet of Things aren’t being programmed to have bruised egos or complain about having their efforts minimized, their work will be easily co-opted.

Maybe, then, there is a hidden class dimension to the Internet of Things. If we start fooling ourselves into believing technology can be our proxy without authoring our biography, we’re just as bad as the privileged elites who get away with portraying themselves as earning their own keep, rather than doing good job downplaying all the work that’s been done for them.