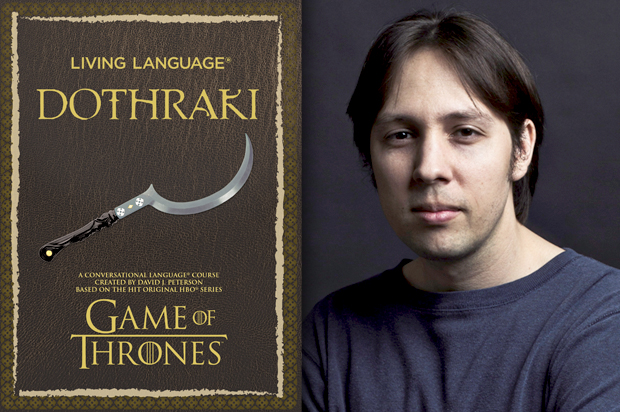

Here’s one way to stave off withdrawal from HBO’s hit show “Game of Thrones” after Season 4 wraps up tonight: learn Dothraki. On Oct. 7, HBO and Living Language will release “Living Language Dothraki: A Conversational Language Course” by linguist and language creator David Peterson. Peterson, a co-founder of the Language Creation Society, joined forces with HBO in 2009 to create the language spoken by the nomadic warriors seen in Seasons 1 and 2. He later invented Low and High Valryian.

Though Peterson has coined 3,800 words in Dothraki and plans to make around 10,000, the course, which serves as a primer to Dothraki culture, teaches readers around 500 words and idiomatic phrases. For those who want to gain a conversational command of the language, there’s also an online component.

But “Living Language Dothraki” is not just for the Dwight Schrutes of the world. Peterson, who has also helped create languages for Syfy’s “Defiance” and “Dominion” and CW’s “Star-Crossed,” has observed that many casual viewers are interested in the fictional languages borne from George R.R. Martin’s book “A Song of Ice and Fire” (judging by the response to the show’s “Monty Python” Easter Egg this season, Peterson’s assessment seems spot on).

Where do you start when it comes to creating a language?

With Dothraki, that was the first time that I was starting with found material. So in the books that had been published up to that point — there were four of them in “A Song of Ice and Fire” — there were about 50 words in Dothraki and about half of those were names. For Dothraki, the first step was cataloging all of those words and seeing how they were spelled and determining how I thought they would be pronounced, both by trying to determine how I thought George R.R. Martin meant for them to be pronounced, and how I thought he was thinking fans would think they would be pronounced, or would plausibly be pronounced, since it was a foreign language.

So I started there, and then, based on that, I analyzed the sound system, both what sounds I felt were represented in those words and how they fit together in the syllables and words. Once I’d done that I filled in any gaps that I saw in the system. I added one sound to Dothraki, which was a “ch” sound, which I thought should be there.

I think the longest phrase was, “a prince rides inside me” — “Khalakka dothrae mr’anha,” which, based on a few phrases like that and “strong boy” (“rakh haj”), I determined the word order of the language: the subject was first and then the verb and the object, adjectives would follow the nouns that they modified.

Why did you even need to create a full language for a fictional universe?

Well, the driving force for all of this, and of course the reason I’m even on the project, is Dan Weiss and David Benioff. More than any other show I’ve worked on, they absolutely set the tone for what’s expected of everybody that’s working on it and the vision that they want to achieve. And really what they want to do, visually and style-wise, is two things: They want to have a show that’s as realistic as possible given the fantasy setting, and they want to, as much as they possibly can, realize George R.R. Martin’s vision. So those two things combined really necessitates a full language, and that was in fact why they hired me in the first place.

They started filling in gibberish for Dothraki and they realized it just wasn’t meeting their realism goals and it wasn’t honoring George R.R. Martin’s vision.

In a show, everything that’s happening on the screen has to be explicitly reified, whether it’s the actors in the background, the sets, the costumes. Everything that shows up on the screen or can be heard from the actors on the screen adds a conscious decision on the part of the filmmakers. And so that’s why they realized that it wouldn’t just pass to throw up whatever for the Dothraki, whether it was just being spoken in the background or whether it was being spoken in the forefront. You can’t have a narrator just jump in and say, “And then he said this in Dothraki.” They need to actually be saying it.

Have you received any direct feedback from George R.R. Martin about the languages that you created?

No real direct feedback except that he likes the languages and appreciates that they exist. I think he’s used them. For example, there was a map book that came out called “The Lands of Ice and Fire” that he did where he fleshed out a lot of maps of his world. And he used some Dothraki to create new place names of the maps.

Not only that, he got my help to translate some of the words. He also did some translations of his own and did them accurately and very well. So I think he likes the languages and he appreciates that they exist because I think he gets the sense that I created them to help flesh out his world, to make it larger and more realistic.

I assume the people teaching themselves Dothraki are going to be some real “Game of Thrones” superfans.

Actually, I don’t think so. There are a certain group of fans that are really, really excited about the language and they always follow the new dialogue that comes up and record it and try to learn from it. There are a lot of fans who, especially if it’s online, they think the language sounds really cool and they would like to look it up but they don’t necessarily have the time to go look it up online. Now with the “Living Languages Course” … you can buy the book and own it. And also if you just wanted to do something quick and convenient you can download the app to your iPhone and there’s going to be a bunch of flashcards you can just flip through and use casually, which is pretty cool.

And then I think for the fans who want to go deeper, that’s what the online course is for. There’s going to be a whole lot more information that is going to be a bit more taxing and require more investment of personal time.

I think we’ve reached a point where you can now find a market for this. And that’s something that we couldn’t even have said five years ago, let alone 20 years ago.

So will taking this Dothraki course make you fluent?

It will take you to the point where you will be able to put together a variety of simpler phrases. Like you should be able to string together dialogue and you should be able to understand dialogue. There are going to be nuances of the grammar that are more for intermediate and advanced, but this will get you through the bulk of standard texts, I think. And if you wanted to go back to Seasons 1 and 2, it should give you a foothold into a lot of the dialogue that’s in the show.

Is 10,000 words still the goal?

It definitely is. The problem is I’ve gotten so busy with so many languages now that I can’t spend as much time with an individual language just to coin new words, which, by the way, is one of my favorite things to do. I don’t know how people imagine the life of a language creator, but for me one of the ultimate joys is to sit down and imagine new words.

Is there a particular world in English that you wish you could create?

Every single language has words in it that don’t exist in another language, or at least you won’t have a single word for — like in Spanish there are two different words for corner — “rincón” and “esquina” — that differ whether the corner is an inside corner or an outside corner. It would be kind of like if you’re looking at the corner of a box from inside the box or outside the box. So it’s like, you can explain that in English. Those specific words don’t exist in English. At least, not concretely. So there are words like that in every language.

One of the things I found that was most difficult is that when I’m creating a language, I often come up with a lot of those words where it’s like, “Oh, that’s a really cool word and there is no word precisely like it in English or any other language I know.”

So as for something we might need a word for in English: There was something I thought of just the other day, which is — and I think everyone knows this feeling — when you pick up a piece of pizza and you’re really looking forward to this piece of pizza with a bunch of toppings on it and then right as you’re about to put it in your mouth your favorite topping falls off onto the floor. Like, ahhhh! And it’s just that feeling you get of grand disappointment coupled with, as it’s running through your mind, ‘Is it safe to pick that topping back up and put it back on the piece of pizza?’ So it’s like you’re thinking about all those things at once the moment you see the little topping just topple over the edge and sail to the floor. So yeah, that would be my word.

What would the word be for that?

Oh gosh, I don’t know what the word would be. I don’t know if you could come up with a good word for it in English [laughs]. Of course, I knew what I would say, there’s a perfect word for this in Castithan, which is another language I created for “Defiance,” which is this expression “Tsworeya!” Like, “Ughhh.”

I don’t know if you’ve followed any of the controversy around the show, but there’s a scene in the very first season of “Game of Thrones” in which Khal Drogo rapes Daenerys. How do you go about creating a language for a culture with a pretty brutal attitude toward women?

Of course, the scene you are talking about in the show happens very differently in the books, where instead of the non-consensual it’s actually consensual. You know, the show and these books are supposed to be part of the same universe. And then, of course, there’s the separate question of where the language exists with respect to both canons and the overall canon. That’s a really interesting question for somebody who’s in an English department somewhere.

It’s a troubled question because what we see of the Dothraki, first of all, is one khalasar, essentially, [one tribe]. So it would be like judging American culture based on the life of one family; in this case a large family, but one family nonetheless. And so it’s a question of how much of what we’re seeing is indicative of this khalasar? How much of it is indicative of these people? And then, of course, you have to filter that through the age that it’s supposed to take place in, the age and era.

We see the Dothraki — and this is especially true of the book, more so than the show — through the eyes of a foreigner. We see the Dothraki exclusively through the lens of Daenerys, Viserys and a little bit of Jorah. So there’s a separate question: Is what we’re seeing being sensationalized? Is what we’re seeing being misrepresented? And are we seeing the full picture of what life is like? Because when it comes to the events of the book what we’re seeing is Daenerys — and what we’re focusing on is Daenerys — and her relationship with Khal Drogo and everybody else. What we don’t see are the relationships of, for example, an average Dothraki husband and wife and children and what their lives would be like if there weren’t this strange foreigner in their band.

So when it comes to creating a language, I keep that in mind because the language represents everybody. For example, you could pick out all of the racial slurs from English and only them and then present them to somebody and say, “What’s this language like?” And you would say, “Wow, this language is really racist.” But that’s just a small, teeny, tiny part of the language. So as a language creator then you have to create the language of those who maybe are not so nice. You have to create the language of the misogynist.

As a language creator, how does it feel to develop this entire language and then have audiences see only stylized snippets of it?

I think this is the key difference between having a language that is effectively a prop versus having a sword or a throne that’s a prop: A physical prop is only ever going to have any reality when you see it on-screen. It has no reality beyond that. But a language is not a physical thing. A language is an idea or a set of ideas, an idea or a system. So when you talk about its reality, it’s as real as it gets the second that it’s spoken.

So I emphasized this idea in my head when I started with this project. I realized that the language I was going to be creating, if the show was successful and people actually end up liking the language, it was going to have a reality that existed beyond the show, perhaps well beyond the show, because of the nature of language itself.

So when I did Season 1, I created 1,700 words of Dothraki — actually a little bit more than that. And a fraction of those were used in the show. But I knew that at some point in time, if everything went well, the language could have some existence beyond the show, and so I wanted to be sure to give it as much character and life as I could, so that if somebody wanted to later on they could pick it up and use it.

Are you in touch with the community of 150 or so people who do speak Dothraki?

Oh yeah. Not everybody, but certainly with a few key members. There are several I’ve met in person who I consider friends now. They had a lot of fun learning the language. It was a different thing for me because I’ve been creating languages for many years. I’ve never had anybody who seriously wanted to learn one of my languages. For example, creating irregularities in the language that took a lot of work to put in there to make the language realistic and then having people try to learn it — they’re like, “Ahhh, geez! This is irregular. We have to memorize that.”

What are you favorite words or idioms in Dothraki?

I was actually pretty pleased with the translation of one of the George R.R. Martin’s idioms. He came up with “sun of my stars” and “moon of my life” and I really like the way “moon of my life” ended up sounding, which is “Jalan atthirari anni.” And then one of my favorites, actually, I don’t think it would ever be used in the show but I came up with a phrase for “good morning” — “Aena shekhikhi,” which is “morning of light.”

Do you consider yourself a big fan of the show?

Oh yeah. I love it. Of course, I’m also going to be one of the fans that’s read all the books and I’ve seen a lot of the script so I know that there aren’t a lot of big surprises.

Goodness gracious, Jack Gleason, who is unfortunately gone from the show … absolutely there could not possibly be a better Joffrey than him. He was incredible. Like every scene. And also my favorite character from the books, Tywin Lannister, Charles Dance (laughs) … he nailed it! I remember, because I read the books first, and so when I first saw Tywin Lannister I thought, “Oh, that’s not really how I pictured him.” And then once I saw what he was doing with the character I thought, “Oh, wow. This is so much better than what I was picturing in the books. This guy is amazing.”

What are some of your other favorite fictional worlds?

I read the “Narnia” books as a kid, that was fun. I grew up an English major so most of the time everything I was reading was set in the real world. But you know the one that was always able to evoke fictional realities that to me were just some of the most awesome and some of the most terrifying was Franz Kafka.

Is that a world that you wish that you could create a language for?

Oh my God. (laughs) It would be incredible to do Kafka if he were doing a book or a story about some bureaucratical language instruction school where this guy is applying for a job and he has to learn a language and it keeps changing every single time he masters it. That would be awesome.