It’ll be another year at least until the next season of “Game of Thrones,” a wait that will leave some viewers with an unaddressed hankering for skulduggery, intrigues and gore, medieval style. Many have already powered their way through all five of the novels in George R.R. Martin’s “A Song of Ice and Fire” series. The sixth book will come when it comes, people; it’s best to cultivate a zen attitude on that front. So how to slake your newfound thirst for doublets, crossbows and backstabbing (or, for that matter, front stabbing)?

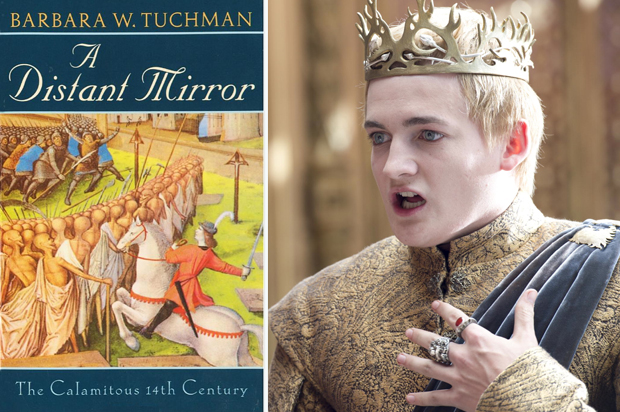

I recommend “A Distant Mirror: The Calamitous 14th Century”, a classic work of narrative history by the Pulitzer Prize-winning writer Barbara W. Tuchman. Scion of a distinguished American family, Tuchman was initially a journalist and largely self-trained as a historian. Her great gift was her ability to braid a prodigious number of facts into strong storytelling, with her easy yet authoritative voice serving as the unifying touch.

“A Distant Mirror,” first published in 1978, is more miscellaneous and anecdotal than Tuchman’s other books. It’s organized around the life of a French nobleman named Enguerrand de Coucy, who survived the Black Death, the Hundred Years War, the Papal Schism and any other number of catastrophes of his time. (Tuchman’s subtitle is no exaggeration.) He led shrewd and valorous military actions in France and Italy, and he married a princess, the eldest daughter of Edward III of England, but Enguerrand was not an extraordinary man. That hardly matters; Tuchman uses him to present a portrait of an age, a time of outrage, atrocity, wickedness, duplicity, vanity and human folly — everything we love about “Game of Thrones,” only with the added bonus that it’s all true.

If you believe nothing enlivens a tale as much as the presence of a really great villain, then meet Charles of Navarre. A grandson of Louis X, he either aspired to the French throne or just liked to cause trouble for the hell of it; nobody knows for sure. Tuchman calls Charles “one of the most complex characters of the 14th century” and describes him as “volatile, intelligent, charming, violent, cunning as a fox, ambitious as Lucifer and more truly than Byron ‘mad, bad and dangerous to know.'” His fellow Frenchmen called him Charles the Bad.

Charles had more lives than a cat and his specialities were implacable grudges, assassinations and elaborate public displays of contrition and reconciliation followed up by a speedy double cross. He persuaded his brother to slaughter the Constable of France (the top military post in the kingdom) out of apparent jealousy; repeatedly offered to act as an agent for France’s enemy, England; enticed one opponent with offers of parley, took him prisoner, crowned him with a red-hot iron circlet and cut off his head; and poisoned a creditor to avoid paying him back. Forever plotting to depose the Dauphin, Charles planned an assassination, but someone ratted him out. He also once burned 300 peasants alive in the monastery where they had sought refuge.

Charles of Navarre was far from alone in his savagery. Charles de Blois, a claimant to the dukedom of Brittany, was renowned for his piety and unusual in his respectful treatment of the humble and poor. But that didn’t keep him from catapulting 30 severed heads over the walls of Nantes or massacring 2,000 “civilian inhabitants of all ages and both sexes” after winning the siege of Quimper.

Tuchman devotes more attention than most historians to the lives of the long-suffering working classes of the time, people routinely exploited, treated like pawns and then blithely raided and slaughtered by invaders. If you’re curious about how medieval townsfolk dealt with their sewage or advertised the wares in their shops, you can learn it here. And while you will not read of a peasant uprising in “A Song of Ice and Fire,” it certainly happened in France in 1358, with a movement called the Jacquerie, whose members reportedly killed a knight and roasted him on a spit in front of his wife and children — although that story might have been invented by their aristocratic foes. At any rate, it took Charles the Bad to put them down.

As for the nobility, they pursued ridiculous fashions, such as shoes with toes so long and pointed they could not be walked in unless they were tied to the wearer’s knee with a silver chain. They actually had live birds baked into pies and then set loose hawks to hunt them as they flew about over the diners’ heads. Young women’s practice of plucking their hairline to achieve the desired look of a high forehead was considered downright “immoral.”

Nothing of the decadence and depravity of the rulers of Westeros would be out of place in 14th-century Europe. As appalling as the flayed-man sigil of House Bolton from “A Song of Ice and Fire” may be, consider the family device of the Visconti family, aka “the Vipers of Milan,” in which a serpent was depicted swallowing a writhing human figure. A clan of legendary depravity, they were nevertheless occasionally outmatched. After “a notable orgy on a river barge during which she entertained several lovers at once including the Doge of Venice and her own nephew,” a Visconti wife murdered her husband “to forestall his same intention with regard to her.” Still, the French gave as good as they got during the war for control of the Papal States. While presiding over the occupation of Perugia, the Abbot of Montmayeur was informed that his nephew had broken into a married woman’s chambers with the intention of raping her, and that the lady had fallen to her death while attempting to escape him by the window. The Abbot’s response? “What of it? Did you suppose all Frenchmen were eunuchs?”

There is, of course, far more to “A Distant Mirror” than outrageous stories like these. Tuchman provides a sense of the economic underpinnings of medieval life that “A Game of Thrones” can only allude to. (Hot tip: The Iron Bank of Braavos is the real power behind every throne.) It will confirm that the fate of Sansa Stark, a pawn in a never-ending series of dynastic struggles, is far more typical for medieval women than that of girl warriors like Brienne and Arya. Well-born medieval ladies were often married off before their ages hit the double digits.

Heresies, invasions, epidemics, diplomacy and a pair of dueling popes march across these pages. Also, a lot more bathing and hand-washing than you might expect. It’s an image of the Middle Ages that overturns many popular conceptions and confirms that however dark Martin’s vision of Westeros may be, it’s not a patch on the real thing.