On Monday morning, not long after people I follow on Twitter started sharing praise of Jill Lepore’s new New Yorker story, “The Disruption Machine: What the Gospel of Innovation Gets Wrong,” Marc Andreessen posted the following tweet: “Why hasn’t anyone invented a robot that will write anti-technology essays for East Coast literary magazines? C’mon, let’s get on it!”

[embedtweet id=”478573591848423428″]

I don’t know for sure whether Andreessen was responding directly to the New Yorker, or to other recent stories that have cast a critical eye on Silicon Valley hype, but let’s just assume for the moment that Lepore was indeed his current target. Haha — good one, Marc! It’s high time that the booming niche of nattering negative technology nabobs gets disrupted! That’ll teach ’em. Andreessen’s followers were highly amused, and made many a mean joke about technology writers failing the Turing Test.

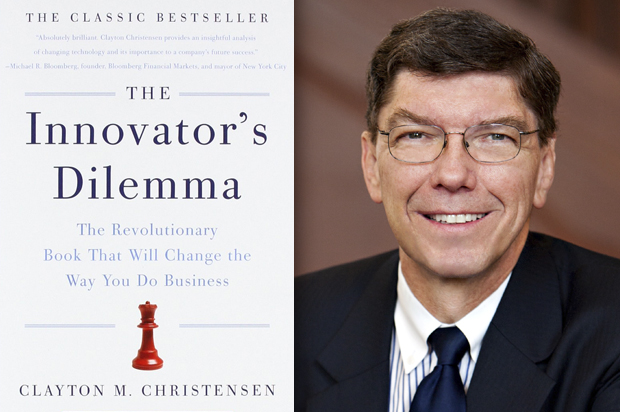

Except, wait. Lepore is not anti-technology. Lepore’s article is a fact-based critique of the theory of disruption as articulated by Harvard Business School professor Clayton Christensen. Of particular interest is her disembowelment of several of Christensen’s celebrated case studies of disruption. It’s a darn good read, and you won’t be able to think about Christensen and “disruption” in the same way afterward.

(For those who have not been previously following along, “disruption” is the process by which smaller, faster, more innovative competitors come along and make preexisting incumbents obsolete. Silicon Valley has disrupted the music, newspaper and books business, and has eyes on education, healthcare and, well, everything else. For a more complete explanation, see Lepore.)

Lepore’s prose, it must be conceded, stings Silicon Valley in some sensitive places.

A pack of attacking startups sounds something like a pack of ravenous hyenas, but, generally, the rhetoric of disruption—a language of panic, fear, asymmetry, and disorder—calls on the rhetoric of another kind of conflict, in which an upstart refuses to play by the established rules of engagement, and blows things up. Don’t think of Toyota taking on Detroit. Startups are ruthless and leaderless and unrestrained, and they seem so tiny and powerless, until you realize, but only after it’s too late, that they’re devastatingly dangerous: Bang! Ka-boom! Think of it this way: the Times is a nation-state; BuzzFeed is stateless. Disruptive innovation is competitive strategy for an age seized by terror….

The idea of innovation is the idea of progress stripped of the aspirations of the Enlightenment, scrubbed clean of the horrors of the twentieth century, and relieved of its critics. Disruptive innovation goes further, holding out the hope of salvation against the very damnation it describes: disrupt, and you will be saved.

I’m guessing we’ve still got a couple of years before the robots learn to write like Lepore, thank goodness. But let’s be clear here: Lepore is not engaging in an anti-technology screed. She’s training her artillery on the way Silicon Valley rationalizes its own behavior as some kind of natural law of progress.

It’s possible to be critical of the way Silicon Valley is agitating for regulatory reform that is designed to nurture Silicon Valley business models without being “anti-technology.” It’s possible to explore the question of how the current pace of technological innovation is affecting jobs and inequality without being anti-technology. It is possible to be critical of how, in the current moment, technology appears to be serving the interest of the owners of capital at the expense of workers without being anti-technology. It’s even possible to love one’s smartphone and the Internet while at the same time critiquing run-amok “change the world” hype.

And indeed, the higher Silicon Valley’s profile rises, the bigger its special interest lobbying political clout grows, and the larger the chunk it takes out of our pocketbooks, the more heat will be applied. Call it a natural law of journalism. For those outlets that still believe in afflicting the comfortable, there’s really no better target right now than Silicon Valley. And that’s as it should be.