Tales of lost horizons always spark the imagination. From the mythical kingdom of Shangri-La to the burning of the library at Alexandria, human history is rife with longing for better worlds that shimmered briefly before slipping out of reach.

Some of us may be starting to feel that way about the Internet. As a handful of corporations continue to consolidate their grip over the network, the optimism of the early indie Web has given way to a much-chronicled backlash.

But what if it all had turned out differently?

In 1934, a little-known Belgian bibliographer named Paul Otlet published his plans for the Mundaneum, a global network that would allow anyone in the world to tap into a vast repository of published information with a device that could send and receive text, display photographs, transcribe speech and auto-translate between languages. Otlet even imagined social networking-like features that would allow anyone to “participate, applaud, give ovations, sing in the chorus.”

Once the Mundaneum took shape, he predicted, “anyone in his armchair will be able to contemplate creation, in whole or in certain of its parts.”

Unpublished drawing of the Mundaneum, 1930s © Mundaneum, Mons, Belgium.

Conceived in the pre-digital era, Otlet’s scheme relied on a crazy quilt of analog technologies like microfilm, telegraph lines, radio transmitters and typewritten index cards. Nonetheless, it anticipated the emergence of a hyperlinked information environment — more than half a century before Tim Berners-Lee released the first Web browser.

Despite Otlet’s remarkable foresight, he remains largely forgotten outside of rarefied academic circles. When the Nazis invaded Belgium in 1940, they destroyed much of his work, helping ensure his descent into historical obscurity (although the Mundaneum museum in Belgium is making great strides toward restoring his legacy). Most of his writing has never been translated into English.

In the years following World War II, a series of English and American computer scientists paved the way for what would become the present-day Internet. Pioneering thinkers like Vannevar Bush, J.C.R. Licklider, Douglas Engelbart, Ted Nelson, Vinton G. Cerf and Robert E. Kahn shaped the contours of the present-day Internet, with its famously flat, open architecture.

Tim Wu recently compared the open Internet to the early American frontier, “a place where anyone with passion or foolish optimism might speak his or her piece or open a business and see what happens.” But just as the unregulated frontier of the 19th century gave rise to the age of robber barons, so the Internet has seen a rapid consolidation of power in the hands of a few corporate winners.

The global tech oligopoly now exerts so much power over our lives that some pundits — like Wu and Danah Boyd — have even argued that some Internet companies should be regulated like public utilities. The Web’s inventor Tim Berners-Lee has sounded the alarm as well, calling for a great “re-decentralization” of his creation.

Otlet’s Mundaneum offers a tantalizing picture of what a different kind of network might have looked like. In contrast to today’s commercialized — and increasingly Balkanized — Internet, he envisioned the network as a public, transnational undertaking, managed by a consortium of governments, universities and international associations. Commercial enterprise played almost no part in it.

Otlet saw the Mundaneum as the central nervous system for a new world order rooted squarely in the public sector. Having played a small role in the formation of the League of Nations after World War I, he believed strongly that a global network should be administered by an international government entity working on behalf of humanity’s shared interests.

That network would do more than just provide access to information; it would serve as a platform for collaboration between governments that would, Otlet believed, help create the necessary conditions for world peace. He even proposed the construction of an ambitious new World City to house that government, with central offices and facilities for hosting international events (like the Olympics), an international university, a world museum and a headquarters of the Mundaneum that would involve a vast documentary operation staffed by a small army of “bibliologists” — a sort of cross between a blogger and a library cataloger — who would collect and curate the world’s information.

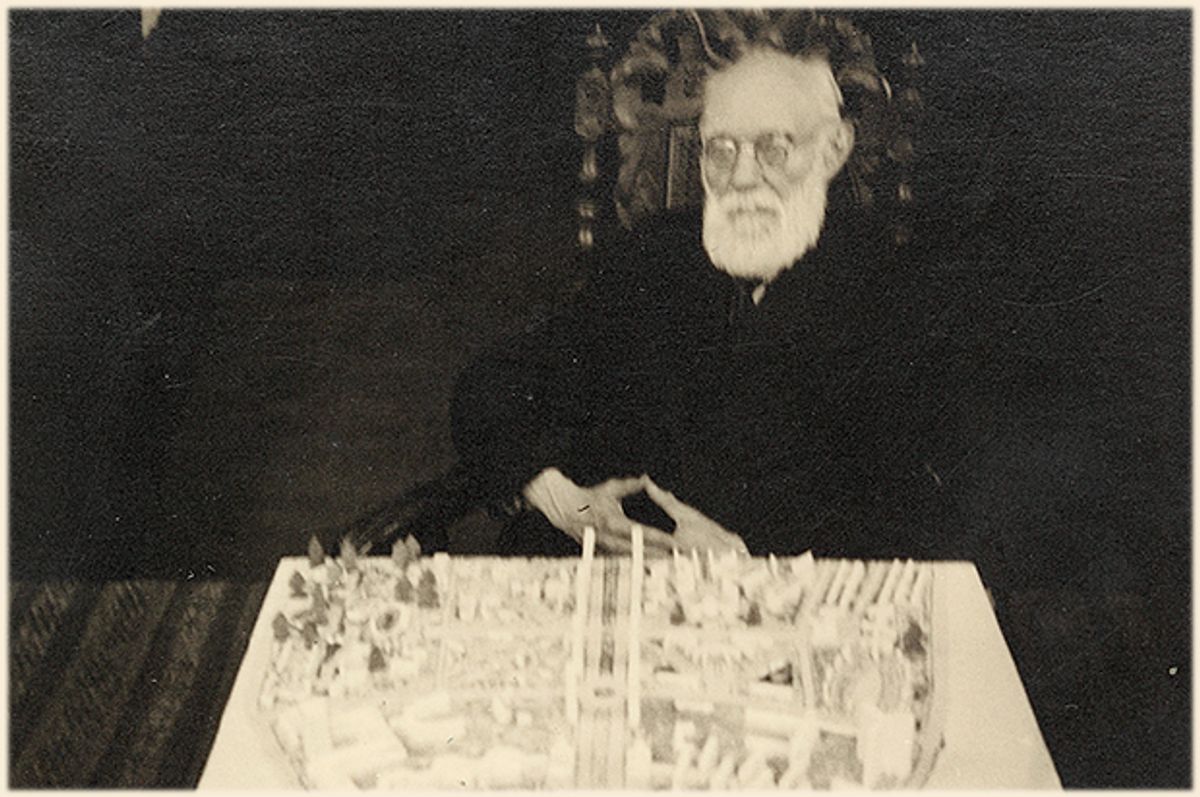

Otlet with model of the World City, 1943 © Mundaneum, Mons, Belgium.

Today, the role that Otlet envisioned for the Mundaneum falls largely to for-profit companies like Google, Yahoo, Facebook, Twitter and Amazon, who channel the vast majority of the world’s intellectual output by exerting an enormous asymmetric advantage over their users, exploiting their vast data stores and proprietary algorithms to make consumers dependent on them to navigate the digital world.

Billions of people may rely on Google’s search engine, but only a handful of well-paid engineers inside the Googleplex understand how it actually works. Similarly, the Facebook newsfeed may sate our appetite for quizzes and cat videos, but few of us will ever plumb the mysteries of its algorithm. And while Amazon may provide book readers with easy access to millions of titles, it is hardly a public library: The company’s primary goal will always be to drive sales, not to support scholarly research.

Otlet saw the network not as a tool for generating wealth, but as a largely commercial-free system to help spur intellectual and social progress. To that end, he wanted to make its contents as freely available and easily searchable as possible. He created an innovative classification scheme called the Universal Decimal Classification, a highly precise system for pinpointing particular topics and creating deep links between related subjects contained in documents, photographs, audio-visual files and other evolving media types.

Otlet coined a term to describe this process of stitching together different media types and technologies: “hyper-documentation” (a term he first used almost 30 years before Ted Nelson invented the term “hypertext” in 1963). He envisioned the entire scheme as a kind of open source catalog that would allow anyone to “be everywhere, see everything … and know everything.”

Overview of Otlet’s cataloging scheme, 1930s © Mundaneum, Mons, Belgium.

Instead of knowing everything, we now seem to know less and less. The sheer mass of data on the Internet — and the difficulty of archiving it in any coherent way — imposes a kind of collective amnesia that makes us ever more reliant on search engines and other filtering tools furnished mostly by the private sector, placing our trust in the dubious permanence of the so-called cloud.

Otlet’s ideas about organizing information may seem anachronistic today. In an age of billions of Web pages, the idea of cataloging all the world’s information seems like a fool’s dream. Moreover, the premise of a single, fixed cataloging scheme — predicated on an assumption that there is a single, knowable version of the Truth — undoubtedly rankles modern sensibilities of cultural relativism.

Otlet’s empirical, top-down approach was rooted squarely in the 19th century ideals of positivism and in the then-prevalent belief in the superiority of scientifically advanced Western culture. But if we can look past the Belle Epoque trappings of these ideas, we can find a deeper, more hopeful aspiration at work.

This is why Paul Otlet still matters. His ideas are more than just a matter of historical curiosity, but rather a kind of Platonic ideal of what the network could be: not a channel for the fulfillment of worldly desires, but a vehicle for nobler pursuits: scholarship, social progress and even spiritual liberation. Shangri-La indeed.

Alex Wright is the author of "Cataloging the World: Paul Otlet and the Birth of the Information Age."

Shares