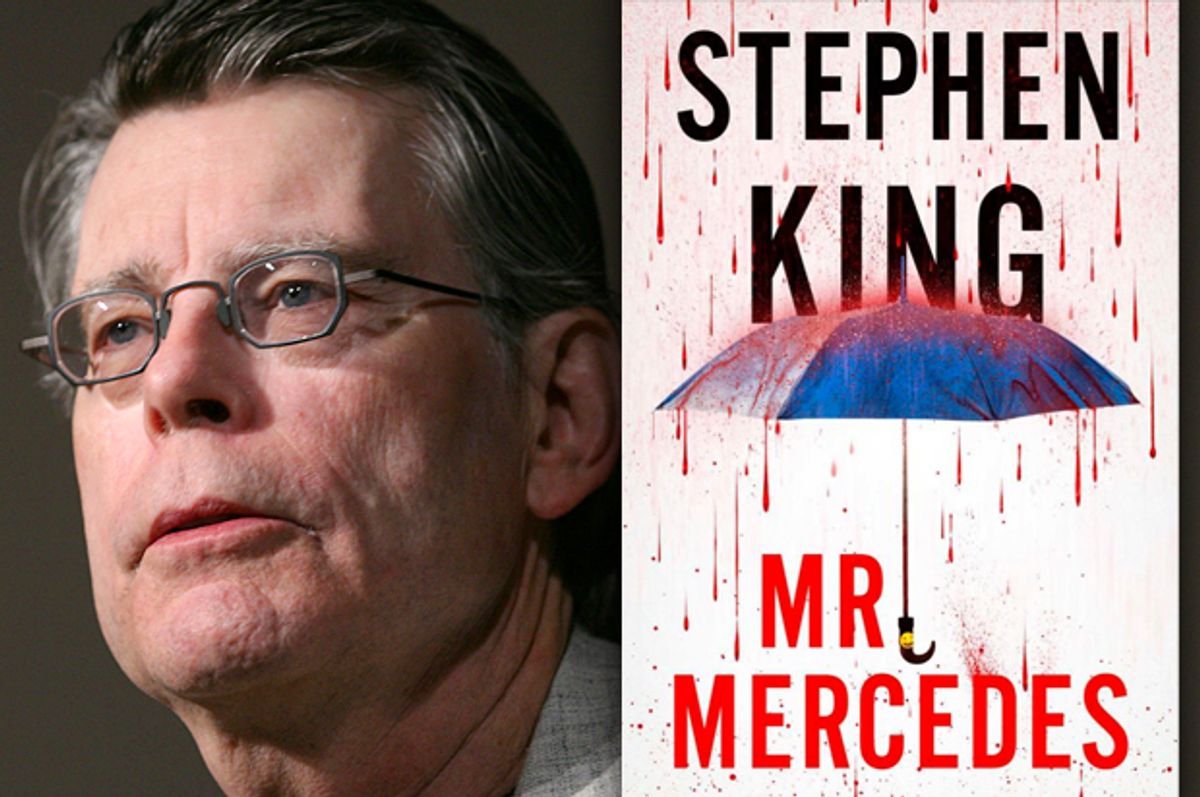

Set in 2010, after the start of the Great Recession and before the Boston Marathon bombings, Stephen King’s latest non-supernatural thriller features a mass murderer whose solipsism and misanthropy inspire him to drive a stolen Mercedes-Benz into a crowd of job seekers at a career fair. Having evaded capture after his first exercise in homicide, Brady Hartfield, the seemingly mild-mannered mid-20s killer, devises a plan to kill and maim thousands more – at a boy-band concert attended primarily by teenaged girls and their parents.

The timing of the release of "Mr. Mercedes” could hardly be less propitious (until we remember that “Black House,” King’s long-awaited second collaboration with fellow horror writer Peter Straub, arrived in stores on September 11, 2001). The novel’s publication date comes a little more than a week after Elliot Rodger stabbed three people to death in his apartment near UC Santa Barbara, killed three others in drive-by shootings, ran down pedestrians in his BMW and then fatally shot himself with his own gun. In the wake of the Isla Vista tragedy, this straight-ahead thriller now makes for uncomfortable reading, in a way Mr. King undoubtedly did not intend.

The protagonist of “Mr. Mercedes” is Bill Hodges, a retired Midwestern homicide detective who, somewhat unconvincingly, is contemplating killing himself out of boredom and regret. Spending his days sitting in an armchair, watching TV and fiddling with a Smith & Wesson revolver, Hodges is pulled from his existential funk by a long, taunting letter from “The Mercedes Killer,” who claims credit for the vehicular massacre that killed eight people and wounded 15. The letter writer also threatens to orchestrate an even more diabolical attack in the near future.

Rather than do the sensible thing -- take the letter to his former police colleagues -- which would end the book after a chapter and a half, Hodges embarks on a personal, covert crusade to identify and capture the Mercedes Killer. The two of them begin communicating via Blue Umbrella, an anonymous messaging system, and each attempts to manipulate the other into making a fatal mistake.

Hodges is aided in his quest by Janelle Patterson, the sister of the woman whose luxury car was stolen and used as a weapon in the City Center Massacre, as well as by Holly Gibney, her anxiety-ridden female cousin, who’s tougher than she seems. And then there’s Jerome Robinson, Hodges’ teenaged African-American neighbor, who’s adept with computers and high tech, yet inexplicably leaves notes written in dialect (“I has mowed yo grass and put de mower back in the cah-pote”) and talks jive in a way not heard since Lionel Jefferson was yanking Archie Bunker’s chain on “All in the Family.”

Let’s get some things out of the way quickly: In terms of quality, “Mr. Mercedes” ranks squarely in the middle of King’s oeuvre, nowhere near the pinnacle of “The Shining” but well away from the abyss of, say, “Dreamcatcher.” Although svelte in comparison to its author’s usual overstuffed page counts, “Mr. Mercedes” is nearly 500 pages of the kind of cat-and-mouse maneuvers that Donald Westlake or Lawrence Block could have handled neatly in 250. It contains some eyebrow-raising supporting characters, a few twists that stretch credulity to the snapping point and an oddly anticlimactic climax. Before May 23, most Stephen King fans would have likely found it flawed but enjoyable.

King understands that genre fiction often succeeds or fails on the appeal of its antagonists, and over the course of his career he has created some masterful ones. At one end of the spectrum are the avatars of supernatural evil, epitomized by Randall Flagg, the Walkin’ Dude, who marshals the forces of darkness after the Apocalypse in “The Stand.” A shit-disturber of the first order, Flagg may be the ultimate King bad guy, appearing in multiple forms in multiple books, always self-amused and ready to spread his cheerful malevolence far and wide. No rationale needs to be given for his behavior. It’s just how he rolls.

At the other extreme are the human bad guys, the sociopaths, creeps and other assorted damaged souls, perhaps best represented by Annie Wilkes in “Misery,” one of the author’s most assured novels. King has had personal experience with “number-one fans” and other brands of stalkers, including the gentleman who used to drive a van festooned with claims that it was actually Stephen King instead of Mark David Chapman who shot John Lennon. Bipolar, hatchet-wielding Annie Wilkes inspires both pity and terror, and King makes her completely and horrifyingly human -- more complex, powerful and sympathetic than most occult nemeses.

Brady Hartfield in “Mr. Mercedes” at first seems to be one of King’s least interesting villains. The chapters from his perspective -- set in such prosaic locations as a failing big-box electronics store, a Mr. Tastey ice cream truck and, of course, his basement lair at his mother’s house -- are something of a slog. Although he keeps it hidden from the outside world, Hartfield is an equal opportunity hater: racist, misogynistic, contemptuous of nearly everyone and everything. There’s nothing of the political extremist or religious fanatic in him. He tells himself that he’s motivated to mass murder by a need to achieve a “high score” and posthumous glory.

There is, however, something in Hartfield’s hateful banality that resonates with what we know about Elliot Rodger. Neither killer, fictional nor real-life, “snapped.” Their atrocities were a long time brewing. Their desperate sense of entitlement and their hatred and fear of women are unmistakeable and gut-churning. Almost despite himself, King gets his portrayal of a mass murderer correct.

King has previous experience with writing fiction that hews a little too close to bloody reality. “Rage,” the high school kidnapping potboiler written when King was in his teens and first published in 1977 under his pseudonym Richard Bachman, is suspected to have inspired school shootings in California, Kentucky and Washington. The novel has been allowed to fall out of print, which King deems “a good thing.”

“Rage,” which can be misread as a celebration of the violence it actually condemns, was written by a young author not fully in control of the tools of his craft. “Mr. Mercedes” is the product of an old hand, an accomplished writer of popular fiction who generally knows what he’s doing. There’s really no need to fret that the book might inspire further mayhem.

But while it can’t be claimed to be either predictive or prescriptive, “Mr. Mercedes” proves to be more nuanced than it first appears. Perhaps it can make its readers think a little more closely about the heart of darkness in American culture.

Shares