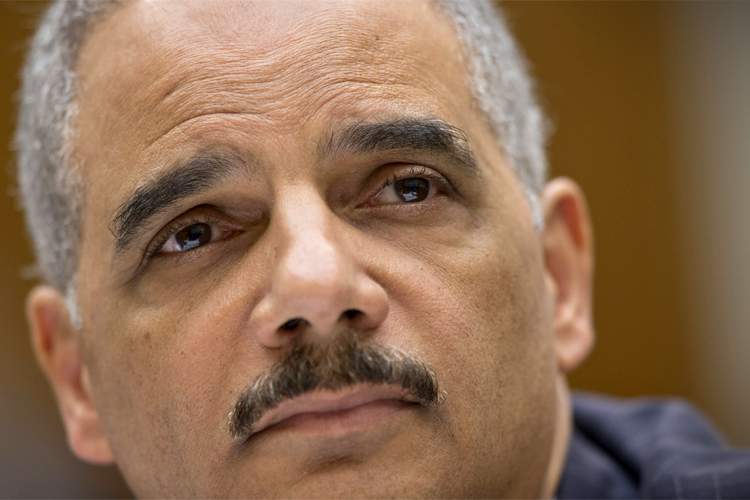

The Wall Street Journal’s Dorothy Rabinowitz wrote recently that Eric Holder has “become, in all, the most racially polarizing attorney general in the nation’s history.” Um, really? Let’s put aside the implications of declaring America’s first and only Black attorney general the “the most racially polarizing” in our nation’s history. Is there any evidence to suggest this extreme charge has an iota of truth?

Rabinowitz, a member of paper’s editorial board, provides three reasons for describing Eric Holder as the most racially polarizing attorney general in American history:

- Eric Holder “charged that the American people were ‘a nation of cowards’ in their dealings with race”

- Eric Holder “would go on to attack states attempting to curtail voter fraud”

- Eric Holder would “refuse prosecution of members of the New Black Panther Party who had menaced white voters at a Philadelphia polling place.”

By way of contrast, here’s the competition for the title of “most racially polarizing attorney general” in U.S. history:

- The attorney general who denied Black people citizenship and upheld the imprisonment and enslavement of free Black sailors. Roger Taney, attorney general under Andrew Jackson, would later become notorious as Chief Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court for authoring the Dred Scott decision, in which he declared Black people “unfit to associate with the white race” and rejected a slave’s attempt to sue for his freedom. Even during his time as attorney general, Taney vehemently argued that Black people could not be citizens or travel freely. Taney delivered a formal position supporting South Carolina’s Negro Seamen Act, a law that called for free Black sailors entering South Carolina to be imprisoned and sold into slavery unless a certain amount was immediately paid for their release. As attorney general, he declared: “The African race in the United States even when free, are everywhere a degraded class, and exercises no political influence… They were not looked upon as citizens…”

Was Taney “racially polarizing”? One senator called him “more thoroughly abominable than anything of the kind in the history of courts.” Eric Holder may have called America a “nation of cowards” on race, but Roger Taney attacked Northern abolitionists for their “wild passions” and for not being “in a condition to listen to reason.” The recipient of his letter? Yet another U.S. attorney general, Caleb Cushing, an enthusiastic endorser of Taney’s Dred Scott decision.

- The attorney general who permanently barred Chinese from coming to the U.S. The uniquely named Philander Knox, Theodore Roosevelt’s attorney general, led legal implementation and enforcement of the most extreme of all the Chinese Exclusion Acts. In the late nineteenth century, large swaths of the North American public began to blame citizens and residents of Chinese ancestry for cheap labor and social ills. This New York Times article attacked Chinese residents for opium smoking and supposedly seducing “young white girls”; others attacked the practice of substitutes being hired to take the place of wealthy Chinese criminals. Racial hatred turned into massacres and laws against Chinese entering the United States. Philander Knox led the passage of the most extreme of these laws, the early 1900s permanent ban upon Chinese ever coming to the United States. Newspapers heralded Philander for this ban against any travel to the U.S. of “any person descended from a Mongolian ancestor which ancestor is now, or was at any time subsequent to the year 1800 a subject of the Emperor of China.”

During the brief movement to draft Philander as a presidential candidate, he was lauded as the man who “successfully defended the Chinese exclusion act from renewed attacks upon its constitutionality” and who “upheld the Chinese Exclusion Act.” What were the “renewed attacks” upon its constitutionality? This may be a reference to the Supreme Court decision in U.S. v. Ju Toy (resolved after Knox’s promotion to Secretary of State), which held that an apparent US citizen of Chinese descent who had traveled outside the US could be barred from returning. It would be forty years until the absolute bar against Chinese immigration would be repealed.

- The attorney general who urged the Supreme Court to order enslaved Africans back to their slave-owners. Henry Gilpin, the attorney general under Martin Van Buren, argued the sensational Amistad case in the Supreme Court. A group of kidnapped and enslaved Africans had overthrown a Spanish slave-ship and escaped to the US. Gilpin urged them to be returned to their Spanish slave-owners. This case was sufficiently controversial (and “polarizing”) that former President John Quincy Adams argued on behalf of the escaped slaves, lambasting the Van Buren administration (including both Gilpin and his predecessor as attorney general, Felix Grundy) for trying to send the escaped slaves to “be tortured, and . . . lives forfeited and consumed by fire” in Cuba. John Quincy Adams described the attorney general’s office as representing the side of “utter injustice,” castigated the administration for “Liliputian trickery,” and declared that he could not read allowed the attorney generals’ arguments “to the Court without astonishment, that such an opinion should ever have been maintained by an Attorney General of the United States.”

The Amistad case was hardly Gilpin’s only racially polarizing act. On another occasion, Henry Gilpin wrote a legal opinion as attorney general that steamboats carrying slaves along the rivers of the United States did not violate the laws against transporting slaves, an opinion he stuck to in the face of a barrage of letters from senators. Other opinions included that “some mistakes [were] committed” in allowing Black people to testify in a court-martial, and regarding the manner of removing Chickasaws from their homeland.

- The slaveholding attorney general. John Berrien, who served under President Andrew Jackson, stands out among attorney generals of the United States for owning slaves. One surviving document testifies to his purchase for three hundred and sixty-two dollars and fifty cents “the negro slaves hereinafter described, that is to say, one woman named Lucinda, about thirty-[illegible] years of age and her male child, about fourteen months old, one girl, named Aun, about eight years of age, and one girl named Kitty about seven years of age…”

Berrien repeatedly represented slave-owners, and reversed past US legal policy finding some acts of slavery to unconstitutional. Berrien represented the government of Spain in urging the Supreme Court to return to Spanish slavers the three hundred chained slaves found on board an illegal slave-trading ship. Berrien reversed the official opinion of a previous attorney general, William Wirt, who had concluded that South Carolina’s Negro Seamen Act (imprisoning and enslaving Black sailors entering South Carolina waters) was unconstitutional. In doing so, Berrien also went against the brave legal decision of a US Supreme Court justice who was handling circuit cases in South Carolina, and had also declared the law illegal and was viciously attacked for it. Despite outrage from British diplomats and ship captains, as well as Northern ship captains and sailors, Berrien declared that such states as South Carolina and Georgia, could imprison and enslave free Black sailors as part of their “regulat[ing of] its own internal police.” John Berrien was also closely involved in the other “racially polarizing” issue of the day: he “strenuously defended” Andrew Jackson’s forcible resettlement of Native Americans onto distant reservations.

The above motley list does not even include such attorneys general as John Crittendon, who argued for fugitive slave laws, and proposed extending slavery across the southern United States as a “compromise” between North and South. Or Francis Biddle, who authorized the Japanese internment camps of World War II. Or Thomas Gregory, attorney general under Woodrow Wilson, whose speech praising the Ku Klux Klan concluded: “Did the end aimed at and accomplished by the Ku Klux Klan justify the movement? The opinion of the writer is that the movement was fully justified…”

So was Eric Holder the “most racially polarizing attorney general in this nation’s history”? Perhaps someone should do a little more studying of this nation’s history first.