It makes sense that thriller authors would occasionally get the urge to set their novels in the book publishing world -- write what you know, etc. -- and besides, so many readers today are aspiring writers that the realm of big-ticket publishing has taken on some of the wish-fulfillment glamor of locales like Paris and Hong Kong. A seven-figure advance on royalties is, for some of us, far more alluring than James Bond's Aston Martin zipping over the cobblestones of Monte Carlo.

On the other hand, the book business isn't exactly thrilling, and efforts to gin up the sort of tension required to fuel a good suspense novel tend to lead to ludicrous excesses. Take Joel Dicker's "The Truth About the Harry Quebert Affair," published in English in the U.S. earlier this year after attaining bestsellerdom in French. (Dicker is Swiss.) In 2012, "Harry Quebert" won a major literary prize in France (the Grand Prix du Roman, awarded by the Academie française) and its American publisher, Penguin Books, reportedly shelled out a handsome advance for the rights in hopes that it might become the next "The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo." No one can accuse Stieg Larsson of crafting deathless works of literature, but for sheer, unadulterated silliness, Dicker has the Swede beaten, hands down.

I know a few publishing people who fume over "The Truth About the Harry Quebert Affair," peeved at the acclaim it has achieved overseas despite both its hamfisted prose and its dopey depiction of the American book business. The novel tells the story of a once-successful but now blocked young novelist trying to clear his literary mentor of the decades-old murder of a teenage girl in New Hampshire while dodging his publisher's demands for a second book. To judge by the Amazon reviews, stateside readers have proven harder to win over than the French, no doubt because Dicker's impression of American culture is peculiarly skewed, as if it's been run through the conceptual version of Google Translate. (He believes, for example, that the Monica Lewinsky scandal was motivated by Americans' puritanical horror of fellatio. He has, apparently, never heard of fraternities nor seen a Farrelly Brothers or Apatow movie.)

But "The Truth About the Harry Quebert Affair" is so deliriously, hysterically idiotic that, far from hating it, I have found it an endless and even endearing source of mirth. It's the "Showgirls" or "Plan 9 from Outer Space" of literary thrillers, so ineptly executed and preposterous that it achieves a perverse splendor. If a 12-year-old boy self-published his fantasy about becoming a bestselling author, with perhaps a little editing help from his too-doting mom and some plot points cribbed from Grace Metalious' scandalous 1956 small-town potboiler, "Peyton Place," he might produce a book like "The Truth About the Harry Quebert Affair." But only if he also grew up in Switzerland.

Dicker's hero, Marcus Goldman, kicks things off by informing us that not only has his first novel "made me the darling of American letters" but it has also sold "one million copies" and made it impossible for him to "walk the streets of Manhattan in peace," without being mobbed by fans. Among the "new rights I’d been granted by celebrity" he savors "the right to buy anything I liked; the right to a VIP box in Madison Square Garden to watch the Rangers; the right to share the red carpet with pop stars whose albums I had bought when I was younger; the right to make every man in New York jealous by dating Lydia Gloor, the star of the country’s top-rated TV show." Lydia Gloor! But before we get sidetracked by the fabulously bizarre names Dicker gives his characters (including a tough, black, small-town New Hampshire cop called Perry Gahalowood), need I point out that this level of fame has been awarded to exactly zero contemporary novelists, ever? The pièce de résistance comes when Marcus is recognized by the clerk in a convenience store at a highway rest stop: "We sold your book here last year," the fellow chirps. "I remember now -- your face was on the back." You have to wonder if Dicker has ever even been to America.

Marcus has a kvetching Jewish mother, as imagined by someone who once read a Philip Roth novel while under the influence of hallucinogens ("I’ve been thinking again about that Natalia you introduced us to last year. She was such a sweet shiksa. Why don’t you call her?"), but his real problem is that a whole year after the publication of his first novel, he still hasn't written a second one. Now his publisher, barking at him like one of the tyrants who ran the old Hollywood studio system, is threatening legal action: "You need to pull a rabbit out of your hat. Write me a great book, and you can still save your career. I’m giving you six months. You have until the end of June." Unfortunately, Marcus hasn't written a word.

Of course, any real publisher lucky enough to have signed a million-copy-selling debut novelist would be handling that talent with kid gloves. We are apparently meant to think that Marcus writes literary fiction (he supposedly wants to be a "cross between Saul Bellow and Arthur Miller," who was a playwright, but never mind). With literary novelists, a five-year gap between books is not unusual. Suing an author to regain even a large advance is very, very rarely done. It's a form of extreme, last-resort bridge-burning likely to scare off other writers and not the way any canny publisher would treat the probable producer of a future cash cow, let alone the author of a current one. A year after the publication of a title as popular as Marcus' debut, most publishers would be wheedling the author to do publicity for the paperback edition; it's much easier to sell more copies of a book that's already a hit than it is to launch a new one.

In other words, absolutely everything about this motivating scenario is wrong, wrong, wrong. But to have Marcus simply run short of money (and perhaps the affections of Ms. Gloor) like any other wastrel of a writer would be too leisurely for Dicker, who instead opts to turn his hero into a hunted man. Marcus seeks the counsel of Harry Quebert, his mentor and the author of a novel that also just happened to sell a million copies. (Dicker loves that number more than Dr. Evil.) It is Harry's sage advice to his protégé that finally rockets "The Truth About the Harry Quebert Affair" into the stratosphere of camp absurdity:

It’s just a mental hang-up, Marcus! Writer’s block is as senseless as sexual impotence. It’s just your genius panicking, the same way your libido makes you go soft when you’re about to play hide-the-salami with one of your young admirers and all you can think about is how you’re going to give her an orgasm that can be measured on the Richter scale. Don’t worry about genius -- just keep churning out the words. Genius comes naturally.

I would like to propose a drinking game. Every time someone tells Marcus he's a "genius," "brilliant" or "a great writer," take a drink. Also, whenever Marcus' agent, Doug, uses the word "shit" in an hysterical phone call ("We're up shit creek"; "Barnaski is going apeshit"; "He'll sue the shit out of you"; "Barnaski is shitting bricks"). By the time you get to the most inane specimens of Harry's wisdom ("You don’t write a masterpiece. It writes itself") you'll find yourself plastered enough to laugh off the number of copies this novel sold in Europe: almost -- but not quite -- a million!

Not all depictions of publishing in thrillers are so utterly clueless, but even the best-informed ones must overcome some foundational challenges. Chris Pavone, a former editor married to a powerful Penguin Random House executive, does a credible job of portraying a certain slice of the book business in his recent novel, "The Accident." A literary agent receives a manuscript from an anonymous source. It turns out to be an exposé on the scandalous past of an Internet and cable-news mogul who plans to run for the Senate. The mogul, who has a mysterious hold over a government operative, tries to get the project squelched. This isn't easy, given the viral way "properties" spread through the media ecosystem, surreptitiously photocopied by editorial assistants and subsidiary rights agents and aspiring film producers. Soon the operative is forced to start killing off everyone who's read the thing.

Pavone gets dozens of finely observed little touches just right -- "the stacks of manuscripts and contracts and reports and things to be filed, the piles that haunt publishing people for their entire careers" unless they quit and deed them to their successors; the hypey way "people in the book business are constantly claiming 'I couldn't put it down' or 'it kept me up all night' or 'I read it in one day'"; the crucial and endangered role of the neighborhood bookstore as the place "where readers discover authors, where kids discover reading." But, unavoidably, when it comes to the main attraction, "The Accident" is unbelievable. If someone wants to make a world-shaking revelation these days, they don't do it in book form. Whether it's the Abu Ghraib photos or the documents leaked by Edward Snowden, they take it to the press or the Internet. And moguls don't need to murder everyone who dares to speak out against them. Campaigns of misinformation and discrediting are equally effective and far less prone to arouse suspicion.

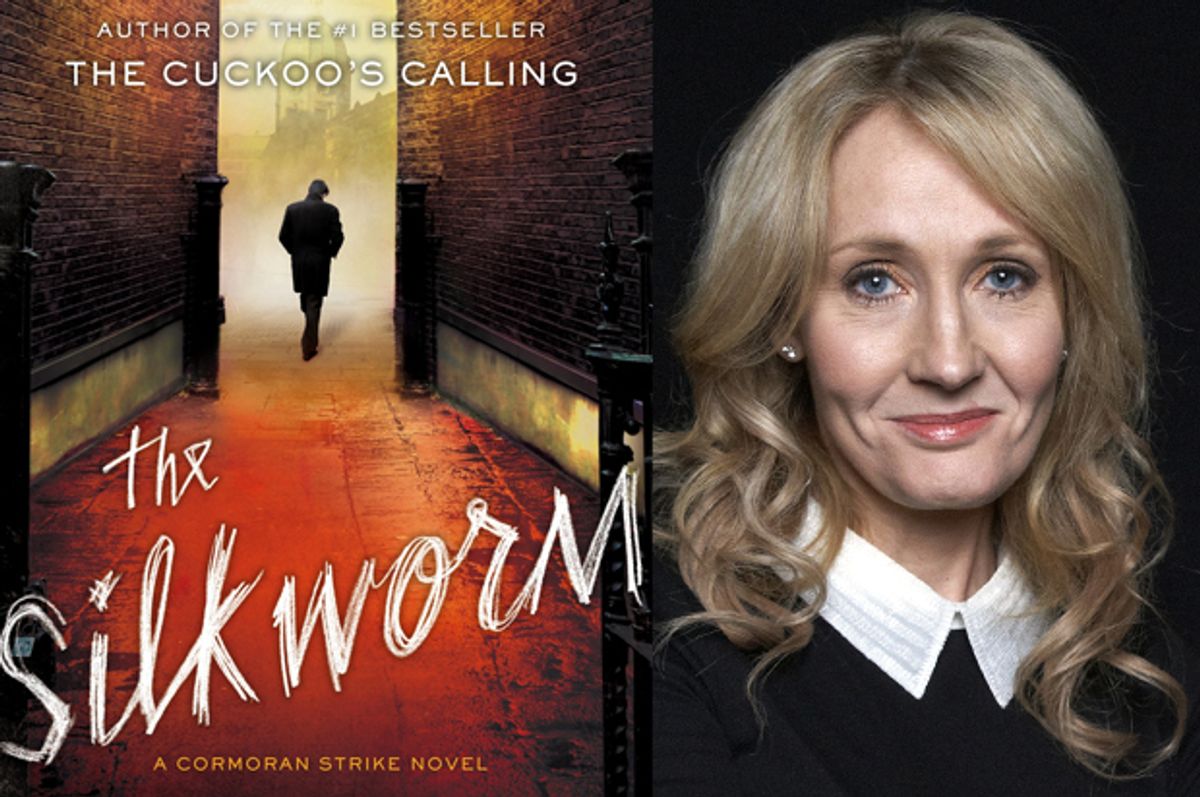

The sorry truth is that a thriller requires life-or-death stakes, and nothing about book publishing rises to that level of urgency. That doesn't mean that writers, those narcissistically myopic creatures, don't sometimes feel as if they're embroiled in such consequential concerns. The author who ditches the agent who whipped her manuscript into publishable condition, the so-called friend who made good but refuses to supply that essential blurb, the critic who wrote that snarky review: such offenders as these can seem tantamount to murderers in the overheated, claustrophobic little world of a literary community. Perhaps that's why the milieu seems best suited to a simple murder mystery, which is surely why J.K. Rowling selected it in her second pseudonymous Comoran Strike novel, "The Silkworm."

Rowling, who writes the Strike novels under the name of Robert Galbraith, may be the only novelist in the world who'd prefer to receive less attention. (Her first Galbraith novel, "The Cuckoo's Calling," sold only modestly, despite excellent reviews, until its author's true identity was exposed.) "The Silkworm" is set among the London literary circles that Rowling must know only from the outside and, in a way, above. Her detective, a veteran turned P.I. who lost his leg in the Afghanistan War, is hired by the wife of Owen Quine, an obnoxious and not especially successful literary novelist, to find her missing husband. Quine turns up gruesomely slaughtered in a fashion that mirrors the ending of his final work, "a perverse 'Pilgrim's Progress' set in a folkloric no-man's-land in which the eponymous hero (a young writer of genius) sets out from an island populated by inbred idiots too blind to recognize his talent, on what seemed to be a largely symbolic journey."

As much Swift as Bunyon, the novel, "Bombyx Mori" (the Latin name for the silkworm), savages all of Quine's associates, depicting them as rat-eating vampires trying to suck "a dazzling supernatural light" from his nipples in sadomasochistic sexual games or cannibal pederasts with rotting genitals. "If anyone's going to touch 'Bombyx Mori' now, it won't be me," one publisher tells Strike. "We're a small outfit. We can't afford court cases." Yet even under the notoriously plaintiff-friendly libel laws of Britain, surely a work as allegorical and satirical, as flagrantly fictional, as this one would not be vulnerable to legal action. You can only libel someone by making statements of fact, which a novel, by definition, is not. That's why someone like, say, Ian McEwan or Martin Amis -- two obvious models for an unpleasant character in "The Silkworm" -- are not going to be seeking damages from Rowling herself.

In the years since Rowling completed the Harry Potter series, she's revealed herself to be a native satirist. It seems to come to her more naturally even than fantasy. "The Silkworm" is not a great detective novel, and Rowling herself is not a particularly great writer. But she is a great storyteller, which means that the skeletal structure of her books -- the reasons why characters behave the way they do and everything that makes a reader care what happens next -- always feels fundamentally authentic, however grotesque the trappings. In this novel, she zeroes in on the vanity, the rivalry, the long-nursed resentments, the wounded pride and the despised and festering love that seem to be the ruling passions in certain literary lives. Just because the stakes are small, doesn't mean the feelings don't run high.

"The Silkworm" features a minor character, Quine's mistress, who has self-published an "an erotic fantasy series called the Melina Saga," and promotes her work with a website "decorated with drawings of quills and a very flattering picture." "A lot of it's about how traditional publishers wouldn't know good books if they were hit over the head with them," Strike's assistant reports. In the pathos of those quills and the huffiness of that reproach Rowling captures the fragility and the vanity of all writers, constantly finding ways to assure themselves that what they do matters, in a world that's always insisting otherwise.

Shares