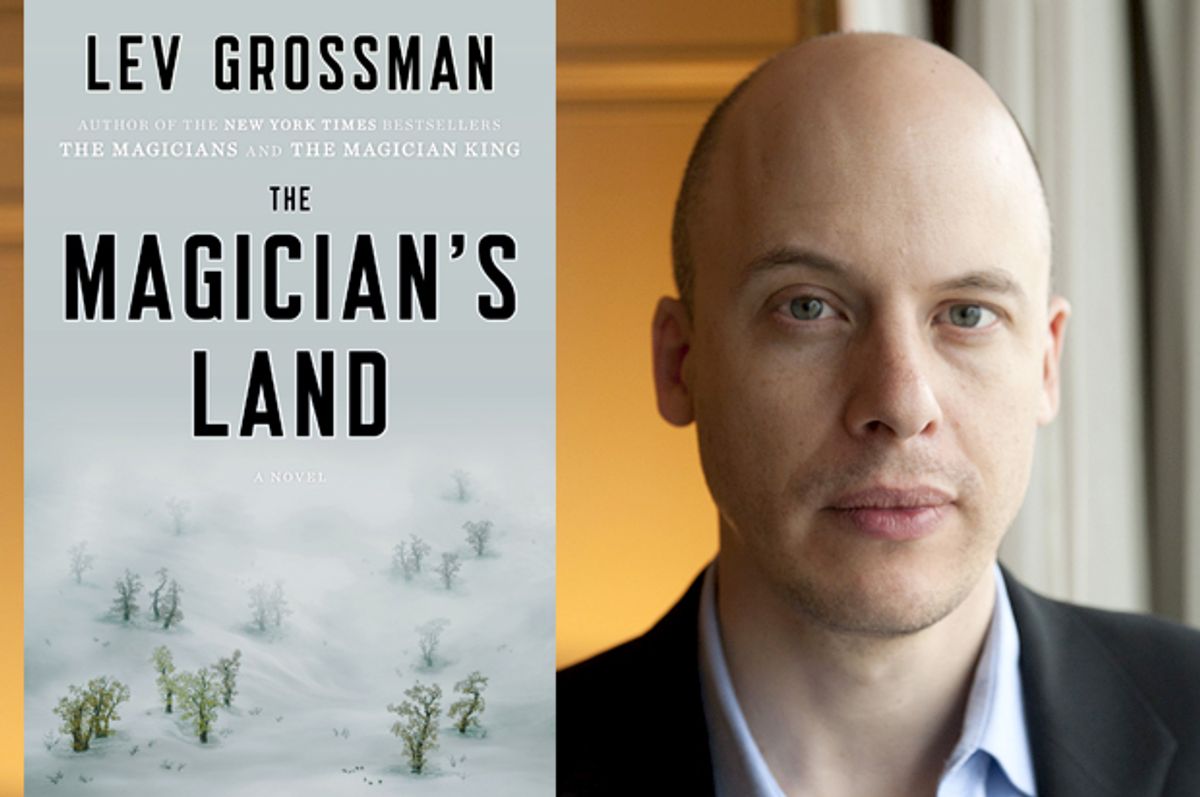

The final novel in Lev Grossman's bestselling, genre-bending trilogy, "The Magician's Land," landed in the No. 1 spot on the New York Times Bestseller list this week, following on more than one enthusiastic review. But when Grossman published the first book, "The Magicians," in 2009, he felt some trepidation. Although it told the story of a young man, Quentin Coldwater, whisked from anomie in contemporary Brooklyn to a secret wizardry university in upstate New York, the novel was written in the sort of wised-up, self-conscious tone literary writers use to convey stories of tottering marriages and waylaid careers. Would it be too realistic for fantasy readers and too fantastical for fans of realism? Grossman, a book critic for Time magazine, describes himself as "risk-averse," but he gambled, and it paid off. The Magicians trilogy has won a sizable and devoted readership, and a pilot based on the first book is currently in production for the SyFy channel. I recently spoke with Grossman about breaking the rules of the fantasy genre and the similarities between magic, writing code and clinical depression.

The Magicians trilogy takes two bodies of source material in children's literature -- the Chronicles of Narnia and the Harry Potter books -- and transfigures them by moving them into adult fiction, with an adult perspective on the world. What were you up to with that?

I thought of it as having a conversation. I believe Harold Bloom's "Anxiety of Influence" theory about authors needing to define themselves through rebelling against a forerunner. In a weird way I really felt that I was talking to J.K. Rowling and C.S. Lewis and trying to tell them about how my life was different from the lives of their characters. I had to explain to C.S. Lewis how poorly I'd been prepared for some of the challenges of early middle age by my obsessive childhood rereading of the Chronicles of Narnia. There was nothing in there about quarterly estimated taxes and midlife depression. And really nothing useful in there at all about sex. I felt like I needed to say, "It's wonderful what you did. I love it and I always will, but I have to tell you there are some gaps here and I'm going to try to fill them in."

It really is like having a conversation with your parents. You love your parents, but they're absolutely maddening and you despise them. It's a both-and situation. One of the primal reading experiences of my life was "Watchmen" by Alan Moore, which was this utterly scathing demolition of the superhero story and all the conventions it stood on -- and at the same time the greatest superhero story that had ever been written. So it is possible to write a critique and a loving homage at the same time in one work and that's what I was trying to do.

To my mind, the most innovative aspect of the Magicians trilogy is that you have this particular type of fictional material -- Fillory [a magical land resembling Narnia], a school for wizards -- that's typically written about in an earnest, somewhat naive voice, which makes sense given that the books that inspired you were for kids. But you've brought to this stuff a voice that is sophisticated, contemporary, adult, like the voice of, say, a Jonathan Franzen novel. There's a metaphor I underlined near the end of "The Magician's Land," where someone is looking at the Castle Whitespire, all lit up before an impending battle, and compares it to a Manhattan high-rise filled with high-powered attorneys pulling an all-nighter. I laughed out loud when I read that. That's as huge a violation of the conventions of the genre as anything else you do. In a way, you're reminding people of the world they're trying to escape by reading about castles.

I'm afraid this may sound kind of glib, but the guiding principle that I use to generate more Magicians prose is to be very tightly focused on how people would actually experience it. When I was an academic for three unsuccessful years, I was really interested in the modernists, the way they very minutely described and itemized this shattered, commodified, disenchanted world we live in. I loved what they wrote, studied it and was very moved by it.

At the same time the modernists were doing that, the fantasists -- Lewis, Tolkien, T.H. White -- were off writing their things. So you had this funny schism in the first few decades of the 20th century. There were these writers who anatomized the world around them and had characters with very rich inner lives. And on the other hand, there were the fantasists, who are not that interested in the intricacies and moment-to-moment psychological experience of their characters and who place them in an imagined, idealized world. It's not so much an external world that's being observed, but the character's internal world that's being projected around them.

So I thought, what if I crossed the streams and tried to write about a fantasy landscape and the character's experience of it the way a modernist would, rather than the way a fantasist would. How would Virginia Woolf describe magic? How would a James Joyce character react to seeing a castle all lit up at night? His associations would be very different from what they should be in a fantasy novel. He'd bring all this stuff to it that you're not supposed to be allowed to bring to a fantasy novel. For some reason I found crossing those streams very satisfying.

Me too, but I can see how it might outrage other readers, because the writing of those fantasists was originally conceived as a repudiation of the modern and many people who enjoy those books enjoy them for that reason.

It's true, and it's horrible, the way I've soiled these wonderful utopian visions with reality. The problem with them is that, 70 or 80 years down the line, they're just not convincing. They just didn't feel real to me. I guess I just didn't believe in them anymore. But I wanted to believe in them! So I felt that I had to bring to them all this stuff that I was so conscious was being airbrushed out of them.

There's always the danger that it could be seen as simply a snarky attack on the genre.

People had to get to know me a little bit. Fantasy is a genre, but it's also a community. If you have a sense that some outsider is coming in and critiquing your genre, you want to know what his qualifications and motivations are. I've been going to conventions, and they've been a great chance to get up in front of people and let them hear me talk, to sort of sniff me to see if I smelled right. It takes about six seconds after people meet me for them to realize "Oh, he's just a fantasy nerd like me."

The flip side of that is an evening I recall when both of us were invited to have dinner with some critics and the novelist Edward St. Aubyn, whose books we both love. He asked about your book and you had to tell him you'd written a fantasy novel, and I thought, "God, I'm so glad I don't have tell Edward St. Aubyn that." He's the quintessential snob.

Yeah, we still talk about that dinner quite often. That was a fucking experience. Probably there will be nobody to whom it will be harder to say, "I wrote a fantasy novel."

Have you encountered much skepticism about what you do from the literary world?

There are still people who believe fantasy isn't a valid form of literature. I used to be much testier about it. I used to have a bit of chip on my shoulder. Really not as much anymore.

Do you feel like you have to make a case for it? Or do you just say, "This is what I do?"

I don't offer explanations unsolicited, but if people want to talk about it, it's my favorite thing to talk about. I talk about the history of realism and the fact that we equate realism and literary fiction as if they were the same thing. But you don't have to go very far back past 1700 to reach people like Shakespeare, Spenser, Dante and Homer. Literature before 1700 was fantasy. There wasn't any difference. It was all gods and monsters, witches and fairies. If you set it in a wider context, then people think, oh, right: Fictional worlds don't have to look like our world in order to mean something.

In a recent Vanity Fair article about critics who disapprove of the popularity of Donna Tartt's "The Goldfinch," the terrible trend of readers who want too much pleasure from reading fiction was blamed on a culture in which adults read Harry Potter.

Yeah, there are very good things about "The Goldfinch," but they're not the things that literary critics generally prize. I think literary critics -- of whom you're one and I'm another -- are much better at describing beauty on the sentence level than we are at talking about the grace of a narrative twist or wonderful pacing or the thrilling tension that a well-put-together narrative gives you. I feel like we're not very good at praising that. We don't have a good critical language for it. I think that's why books with that kind of narrative flare lag behind the more non- or anti-narrative novels in critical reputation.

When you're writing about something like magic, you're trying to make the reader believe -- for a while, at least -- in something that literally doesn't exist. Your readers can't draw on their lived experience to imagine magic, what it feels like or looks like or smells like. In a way, by perceiving it, your characters have a seventh sense that real people don't have. How do you get readers there? Do you base it on, say, electromagnetism?

I think about this a lot. It was one of the areas where I felt I was free to explore because Rowling, for example, doesn't describe her magic in great detail, the way a modernist like Woolf would. I wanted to make sure that when someone cast a spell, you always know what it smells like. The magic in "The Magicians" is cobbled together out of nonmagical things. Definitely electromagnetism. One of the characters, Julia, compares the smell of Quentin to the smell of a Van de Graaff generator, which is something that made a big impression on me at the Boston Museum of Science when I was a kid. Likewise I had the typical suburban teenager's obsession with fireworks. The smell of gunpowder and what it's like waving this tube around when you're not sure what's going to come shooting out of it and which end it's going to come shooting out of and maybe it will blow your hand off.

And music, as well. I was pretty serious about the cello for about 10 years. That sense of this thing in your hand that's producing harmonics and buzzing and you're struggling to get it just right so you get this perfect effect, even though it's this imperfect device and your body is imperfect. A lot of that experience went into magic.

Computer programming is another element of your magic.

Absolutely. With Julia, it's hard to tell where the coding ends and the magic starts.

I often think that we have such a surge of interest in magical narratives now because we're surrounded by all these digital objects, technology that every day demonstrates that old Arthur C. Clarke adage by being indistinguishable from magic. Yet we know that there are wizards who make these devices do what they do, even if we don't understand it ourselves.

That's a good point. Magic is a language that, when you say it, affects the real world and makes things happen. Computer code is like that, too, a language that makes things happen. It's important to me that my magic be a little bit inconsistent, too. It behaves in a pseudo-orderly fashion. It's like a language, and with a language there are all sorts of rules you can come up with to try to describe it, but there's always exceptions. It always escapes being completely codified and quantified.

Including magic in a story always invites people to think of it as a metaphor for something. I remember after I read "The Magicians" I thought that Brakebills was like the Ivy League, this sought-after, elusive place that once you get out of it you hit a post-graduation slump into decadence and indecision about what you should do with these powers bestowed on you. What are some of the things other readers think it stands for?

The big ones that I get are definitely writing, which is completely fair. A useful skeleton key whenever you're reading fantasy is if you're wondering how the author feels about literature and writing, watch how they describe magic. But the other ones are addiction -- Julia's experience of magic has a lot to do with drug addiction and drug culture. But most of all, people identify magic as being about depression and the struggle to recover from it. If there's a demographic I reliably do well with, it's people who have dealt with depression. I hear from them about it a lot. I find that very gratifying because I was struggling with depression when I wrote "The Magicians." Much less so now. But at the time I was really in the grip and looking for a way to write about it.

But the magic itself doesn't represent depression surely? Depression seems so disempowering.

When you're depressed, when you're in bed and feel like you can't get out, you can't imagine doing work or accomplishing anything or anybody loving you. So when you look around you and you see these things happening to other people, they look like magic to you. They look that exotic, that strange, that impossible. And when you begin to crawl out of the pit and reengage with the world, it seems very magical. It felt as though getting out of bed yesterday was impossible, but now you're doing it. Just by returning to daily life, you're a magician.

It can't be easy to reconcile the worldly outlook of the Magicians trilogy with the sense of wonder that many readers turn to fantasy to experience, the same naive joy that Quentin reencounters at the end of the "The Magician's Land" and that makes the ending of this book so satisfying. It's hard to do that with damaged, testy and cynical adult characters.

I see the cynicism and testiness as the flip side of this very hopeful sense of wonder. People with that kind of cynicism, and I've got a lot of it myself, it's a way of managing the un-Narnianess of the world around us and our disappointment with it. That particular currency is backed with a deep longing for a truly fantastic world which never appears. Janet and Eliot [two of Quentin's friends who end up as king and queen of Fillory] are the ones who end up really putting in the years running Fillory. They're the ones, because they're cynical and angry, who need Fillory the most.

Shares