In the need for some climate optimism? Look no further than Emiliania huxleyi, or Ehux, a “globally important” phytoplankton species that, new research suggests, can evolve fast enough to outpace the dramatic impact global warming is having on the world’s oceans.

Coccolithophores like Ehux are already known to be a hardy creatures: they’re able to thrive nutrient-poor environment, giving them an advantage over other phytoplanktons. Their kryptonite is their calcite scales. The carbon dioxide we’re pouring into the atmosphere is being absorbed by the oceans, altering their chemistry in a process known as ocean acidification. Like oysters, crabs and other shelled creatures, coccolithophores risk dissolving in rapidly acidifying waters.

But the single-celled, microscopic species has another trick up its sleeve. According to a study published Sunday in the journal Nature Climate Change, Ehux can thrive in waters as warm and acidic as they’re predicted to be in the mid-2100s. When exposed, in a lab, to what researchers called “the most stressful future ocean scenario,” populations of the coccolithophores evolved so rapidly — they’re capable of producing nearly 500 generations in one year — that they were able to fully adapt and recover. For some reason, they fared best when exposed to the combination of acidity and warmer temperatures: an added advantage, seeing as how they can anticipate both in the real world.

Here’s how the adapted species did after a year of adaptation, as compared to a non-evolved control:

“What they found basically gives us a little bit of hope that some organisms may be able to adapt — to some degree,” Debora Iglesias-Rodriguez, a University of California at Santa Barbara biological oceanographer who was not involved in the study, told Climate Central. And speaking with Reuters, Thorsten Reusch, one of the study’s authors, was careful not to fall in the trap of suggesting that his findings somehow indicate that global warming isn’t going to be as bad as we think. This was only one species, after all, and it only proved able to adapt in laboratory conditions, free from other threats like predators and disease.

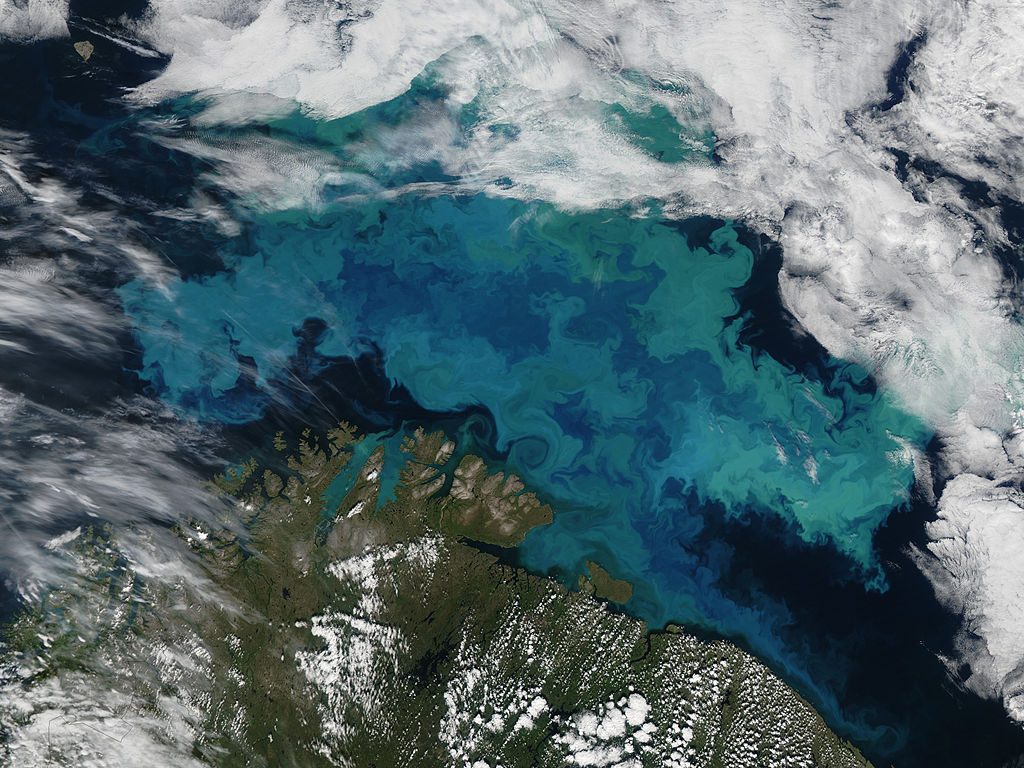

So it’s not the most encouraging news we’ve ever gotten. But coccolithophores are important: Not only are they a major source of food for other marine life, they also absorb carbon dioxide. As NASA rather charmingly put it, “each time a molecule of coccolith is made, one less carbon atom is allowed to roam freely in the world to form greenhouse gases and contribute to global warming.” It’s likely the species won’t be able to outrun climate change forever, says Stephen Palumbi, a professor of biology at Stanford University. Still, he added, “perhaps these abilities will give some important marine life a few more decades than we previously thought.” At least it’s something.