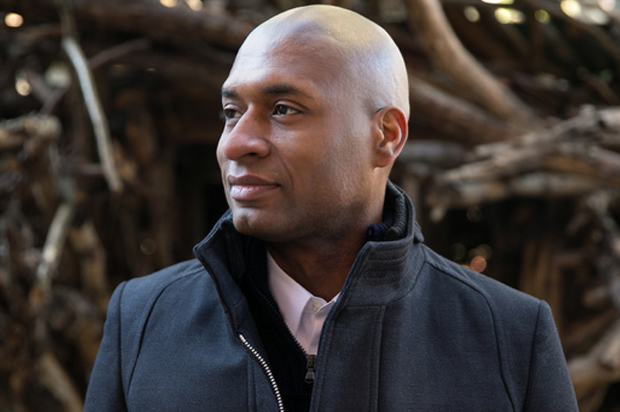

Prior to this weekend, most people, including even the most avid readers of the most influential opinion section in the world, knew New York Times columnist Charles Blow for his thoughtful but measured pieces on American politics and society. But after an adaptation from his upcoming memoir, “Fire Shut Up in My Bones,” went viral, millions of readers discovered that Blow is much more than simply an accomplished pundit. He’s a survivor — and one who proves that survival can be much more than simply not giving up.

A raw, intense and often powerful book, “Fire Shut Up in My Bones” is Blow’s story of how he grappled with the anguish, confusion and rage that grew out of a terrible childhood sexual assault. But it’s also the story of how he was able to ultimately confront his psychic injuries and spiritual demons and build a rich and full life for himself, one in which he understands who he is, what he believes, and how to find peace and love in the tumult of memory and experience that makes up life.

Salon spoke with Blow recently about his memoir, his motivations for publishing it and how writing it forever changed the way he sees his past as well as himself. Our conversation is below and has been edited for clarity and length.

Engaging in the kind of public self-reflection that’s inherent to a memoir can be a really harrowing and vulnerable experience, I’d imagine. What made you want to share something as intimate as your life story — particularly its most painful chapters — with such a large audience?

I started writing the book probably nine years ago, and I wasn’t writing a book, that I could tell. I had a long commute — I was commuting to D.C. — and I was writing scenes from my life that I thought I could package as short essays and maybe sell to magazines or something. It was just things that I thought were interesting … The more I wrote, the more it started to feel like it was a book, although … because I didn’t start with the idea of writing a book, I didn’t have a narrative worked out in my mind.

But in 2009, all that changed. There were two little boys, both of them were 11 years old. One of them was in Boston, and one was in Atlanta; and they both hanged themselves, 10 days apart from each other, because they had both endured a tremendous amount of homophobic bullying. I immediately thought, “This can’t happen.” And I know that feeling [they felt]. I know that feeling of despair, tremendous despair, ostracism, feeling like there is no way out, being too young to even have the language to know how to express it.

And knowing that I did have that language, and that I did at least share some of the experience of bullying and feeling like suicide might be a way out, and that I could write about that sort of pain, and what a life looked like if you walked up to that precipice, but didn’t go over it; and what the rest of that life was going to be like. There would still be struggles, and there would still be questions, but you could survive. That was the genesis of the book.

Once I realized that’s what I was writing, then I think this particular form, memoir, demanded a certain level of unflinching honesty. I don’t think you can half-write a memoir, because the reader, in my mind, recognizes when you hold back. So either you do it or you don’t do it. That’s the way I look at it. And I decided to do it.

Did writing the book cause you to reevaluate some of your memories? I find that sometimes what I recall from my childhood is not what others who were older and there at the time remember.

Oh, absolutely. And in fact, the manuscript opens with misremembrance, which is that I thought that my great-grandmother had died because she turned to see a gift that wasn’t there. In the process of writing, of asking my mom, relatives, friends, everybody about things as they happened, I asked my mom about that story. She said, “No, that’s not how it happened. We had gathered because we knew that she was dying.” I thought that that actually made the manuscript better, because it’s real that children will misremember things. So writing that it had been misremembered, in the manuscript, I think actually made it stronger, and vouches for the intent for absolute honesty in the telling of it.

There are many smaller instances of having to do emotional archaeology, where I go to the same places over and over and over in the course of many years, like the old house where we grew up — because it was still standing at the time — and I would just sit in the room that I used to sleep in … It helped me both in my remembrances, but also kind of setting scenes. I could be in the space and make sure that the way I remember it was in fact the way that it was.

Going to the graveyard and to the church and to the school and going back over and over many, many times, and looking at every photograph that my mother had … She has many photo albums, and I would just pore through them to make sure that the way I remember things looking was in fact the way they were captured in photography. So checking a memory, I think, is part of the memoir-writing process, because we are humans, and humans are fallible, so you need to back up what you remember with actual evidence.

Did those revisions ever go so far as to cause you to take a second look at the narrative of your own life you’d been carrying around all these years? Were there any realities or contrary memories that you came across that were especially inconsistent with your life story, as you knew it?

It wasn’t as much as an inconsistency as memory … I think we remember how we feel more than we remember the actual activities. How something makes you feel sticks with you. And my feeling about things had hardened.

As I was writing … and I could see it on paper and make connections between things, I think I gained a lot more empathy for people in some cases. And in other cases, where I thought people infallible, I saw them as more human, and saw that they could make mistakes and I could still love them — and that I could make mistakes, which I think is probably even more important, and that I could acknowledge and write those mistakes, and see them in the context of an entire life and realize that that is the human experience, too. No character has to be perfect in order to be human. In fact, our foibles are part of what make us human.

One of the parts of the book that I found most harrowing and I expect will inspire much discussion is your treatment of your time in a fraternity, both in terms of the close bonds you forged but also the really intense amount of hazing and bullying you were made to endure. Looking back, do you think Greek life does enough good things for students that it’s worth saving and reforming — or do you think it might not be worth the trouble?

It’s a complicated issue, because … most of my best friends are still the people who I met in that experience. At the same time, I’m a 44-year-old man now. I can look back at that experience and realize just how wrong we were — how tragically wrong we were — in thinking that hazing was not just the only way to have people develop relationships, but that it was kind of a compulsory part, it was a traditional part of it — that we needed to do it because there was some architecture of history that was compelling us to do it.

Even today, trying to get kids to back away from that idea is very difficult, because the hazing process, as I experienced it, was this enormous group trauma. And because it was so traumatic, it did exactly what they said it was going to do: The victims of the trauma bound together. But I am convinced that there are better, safe, easier ways to build relationships, because I see it happen as an adult, and I can see myself having strong relationships with people completely separate and apart from experiences like that.

It’s not necessary, and it is not just dangerous to the people who submit themselves to that process, it is also dangerous, I think, in a way that we don’t talk about as much, to the people who administer hazing, because I think it’s morally corrosive. If we have so many young people who are participating in something that is so deadening to the soul, I don’t know what that says about who comes out of that.

And these are not the slacker kids; they’re the kids who actually go to college. In many cases they’re the kids who are exceeding in college and likely to be our future leaders. And I really think that trying to get at that and unwind that and show that there’s a better way forward and a better way to make real, lasting relationships is absolutely necessary.

A lot of people think of Greek life on a college campus as a completely frivolous thing, and I wanted to treat it seriously, because I actually believe that the issue of hazing doesn’t get treated seriously enough. There are so many kids who take part because they just assume that it’s just part of a rite of passage.

Another element of the book that I found interesting, and which touches on something I think has always distinguished you from some of your fellow columnists at the Times, is your relationship with the South, which is much more complicated than I think many coastal New York Times readers might expect. How do you conceive of your Southernness and what effect does it have on your work?

I actually celebrate it. One of the things about a group of columnists is that you actually want to be different in some ways, to be like an orchestra. Everybody plays a different instrument, but together it sounds good.

For a very long time, I tried consciously to erase all remnants of my Southern upbringing, and becoming a columnist has allowed me not only not trying to erase it, but in fact celebrating it and embracing that idea, because it is the sound, or the rhythm, or the beat of my writing that is most authentically and uniquely me. And I think that it separates me to some degree from many of the other people who write at the Times, and also in other places.

So now I relish the idea that I’m from the South, and I try to think about the great Southern storytellers when I’m trying to tell a story; and I try to think about the people who I would have known in the South when I’m telling a story, as if I’m telling it to them. It’s a complete turnabout for me, and one that I love.