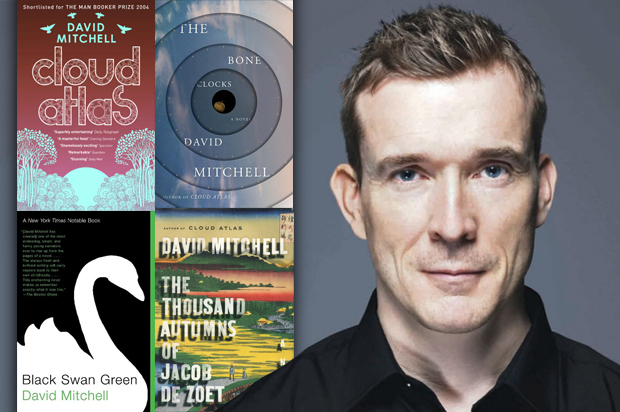

David Mitchell is simultaneously one of the most beloved and critically acclaimed novelists alive and a writer whose new book has been met by sharply — even harshly — mixed reviews. Besides his shimmering coming-of-age novel, “Black Swan Green,” — a book that’s hard to imagine being improved even a little bit — his work ranges widely across continents and centuries, blending character-based “literary” fiction with science-fiction, fantasy and adventure stories. He manages, in books like “Cloud Atlas,” to muse on the nature of storytelling itself without lapsing into arid academic theorizing.

His latest novel, “The Bone Clocks,” draws from the smalltown English milieu of “Black Swan Green,” the continent-leaping of “Cloud Atlas” and “Ghostwritten,” and amps up the genre content in a way that has split critics. “‘The Bone Clocks’ — a perfect title for a novelist who’s always close to the soil and orbiting the heavens in the same breath — is a typically maximalist many-storied construction,” Pico Iyer writes in the New York Times Book Review. “Mitchell writes a crunchily grounded, bitingly Anglo-Saxon prose that somehow makes room for the supernatural, as if D. H. Lawrence were reborn for the digital age.”

But many readers have been less charitable about “The Bone Clocks,” which begins with the pub-owner’s daughter Holly Sykes, 15, fleeing across South England from her parent’s house because of a fight over a boyfriend.

“David Mitchell’s new novel enthralls, soars and crackles, but in the end, it lets you down,” William O’Connor wrote in a The Daily Beast review, the headline of which calls the book “Fun But Mostly Empty Calories.” Salon’s Laura Miler judged the book a great ride until it comes crashing down in its fantasy-infused fifth section. “This new novel represents an uneasy attempt to fuse the disparate veins of Mitchell’s work, the brilliant prose mimic and genre buff with the quieter literary observer of the human condition. Other writers have made such crossover gambits work, but Mitchell, alas, stumbles.”

We spoke to Mitchell about the future, the past, his critics and Talking Heads while he was visiting New York for a reading.

I just finished “The Bone Clocks,” and I’m thinking about your storytelling. You seem like the kind of jazz musician who can go up and play chorus after chorus after chorus without breaking a sweat. Is storytelling easy for you? It seems to be like a melody that just keeps unfolding.

Oh, thank you. Bless you. I sweat. I think all jazz saxophonists do. It’s also my job to conceal the fact that I’m sweating, and for that to be gone by the time it reaches the reader. So yeah, I go wrong and I go down blind alleys and bark at trees and follow red herrings. But I have to fix what goes wrong and rewrite and disassemble and re-assemble so that by the time it reaches your hands, it looks effortless. But no, it isn’t. It’s craft and graft over.

Interesting. There’s a fair bit of science in your work. There’s a bit of religion. There’s a bit of myth and folklore. There’s sometimes what seems like spirituality, especially in the new book. It makes me think of an Arthur Clarke line where he said any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic. I wonder if that phrase ever crossed your mind while you were working on this book. Is it science we’re seeing here? Is it religion? Is it myth? What is it you’re doing exactly?

It is a great line. I do remember thinking ‘You can’t get involved in the particle physics of fantasy.’ You can take it down to a certain level but if you get too involved in the particle physics then it’s not [useful] to continue. So I guess we have a branch of science that even its practitioners do not understand, that they may as well call magic. But that does have its own laws, like the laws of thermodynamics, like the laws of science, it’s just — I guess I know what those laws are but they never have to be stated in the book. So I try to keep character as part of the Venn diagram, with science and magic, and then in the middle they intersect.

We’ve heard over the years about your influences from other writers, from Japanese novelists to Ursula Le Guin to others; I wonder if film has been an importance influence on your writing, especially for “The Bone Clocks.”

I think film has been an importance influence on any novelist born from the 1940s onwards. It sort of altered how novelists edit things and it’s altered how we do dialogue. Something like “Game of Thrones” is altering how we think of long-form narratives, polyphonic symphonic structures with multiple strands. And we look at these things in editing, and we think “How can we do that?” I think a number of writers do, so yeah.

Are there filmmakers that interest you or have shaped you more than others? You must have gone through a Japanese film geek-out at one point or the other.

I haven’t really had a binge watch session but I’m really interested in the filmmaker Hirokazu Koreeda at the moment. He had a beautiful film called “I Wish” and there’s a more recent one called “Like Father, Like Son.” And these are non-violent for the most part, non-magical. Very realist, very straight, but quite exquisite, deep, subtle character portraits. I’m very into him at the moment, and Kurosawa, of course, it’s mythic. Sometimes a dream-like quality that I’m not sure to what degree I kind of see him, and am influenced by him and wish to emulate him. I don’t really know that. Anything you see that impresses you, does influence you in that sense. It reminds you how high the bar needs to be. So more indirect than direct.

You write in a lot of different voices in this book and in all of your books, you specialize in kind of first-person voices that range from different genders, different nationalities, people living in different centuries, even. I wonder if it’s more fun for you or easier, how they compare, writing characters like you, characters different from you, and also characters who are despicable. There’s a kind of narcissist bastard in at least each of the books I’ve read of yours. Are those more thrilling egos to channel than perhaps the more humble characters?

That’s a good question. There are different pleasures to be had writing different kinds of personalities. If it’s hard work, it’s usually a bad sign that you haven’t got the voice right. But the nature of the pleasure changes. Of course, any actor will tell you about the pleasures of playing the villain, the pleasure to be had in creating a character who violates the moral rules that you at least inform to yourself. Yet there’s also a different kind of pleasure to be had from just creating someone who’s morally decent and put in difficult situations where his responses are restrained by his or her decency.

It’s interesting to write a character that’s different from yourself. It’s more of a technical challenge, of course, you need to select or imagine someone and the further away from home you go in terms of gender and ethnicity and time and class. But then the rewards of making it work are also greater. So in a way, you can’t go wrong. They’re all interesting to do, but they’re interesting in different ways.

With Holly, you have your first female character that I can think of who you speak through for so much of a single book.

Yeah that’s right. The trick with Holly, of course, she’s on the other side of the gender divide with me. There were kids like her in my school that I admired from afar.

My wife helped very much with Holly. I think the right way to do a female character is not to over do it. Not to be seen to be making a point about talking about specific, basic, anatomical differences. Not to be seen to make a point of putting in things only women would know. You need to do it more subtlety than that, otherwise you look like a prize turkey.

[laughs]

Well you do, don’t you? There’s a line from a well-known British writer I won’t mention that’s kind of infamous. It’s where a first-person female narrator is going outside on a cold day —and it’s really embarrassing and I’m driving in a car with two women and I’m always embarrassed to say what I’m about to say — but this writer actually says … I can’t believe I’m saying this, ”A gust of cold air made her nipples hard.” That’s just an embarrassing pile of crap. You can’t say that without looking like a prize turkey. So I apologize to you but it was an example of how you have to watch out as a man writing female protagonists; you can’t do that kind of thing.

You have a literary agent in the book say that “a book can’t be half fantasy any more than a woman can be half pregnant.” And yet your book is half, or at least in some ways, part fantasy and half something very different. I wonder if you were, with that line, anticipating the reception this book might receive.

Is that a subtle way of suggesting I’m trying to inoculate my book against every negative criticism by Internet critics and cutting them off at the knees?

Perhaps.

I’m not… I’m not naive enough to write a book ahead of time against criticism. The moment you put your head above the ramparts you expose yourself to a good stoning or a volley of tomatoes. But I don’t think about genre. This is how I live professionally. This is what I do. I like to test lines like that, whether they’re true or not. And it’s justified by the text. It’s not just me being smarmy and post-modernist. It is something a literary agent would say, so it’s justified by the text, I feel.

Well, the issue I’m getting at is that your book has been very warmly and enthusiastically received by a lot of people. Some readers have thought the fifth section, which I won’t spoil for readers, is a departure in some ways, perhaps a culmination in other ways. But it’s different in style than the rest of the novel. I wonder if the book would work — if the narrative, the logic of it, the plot of it, would work if that part hadn’t been in there or had been much leaner and thinner.

It’s as lean and as thin as I could possibly make it and still give some coherence to who the Horologist are and who the Anchorites are and why they are at war with each other. I could have left even more of it out but I think I would’ve had more question marks than clarity there. You were right that there are readers who will be fine with parts on through four, who will get to part five and think “I don’t do the paranormal; I don’t do fantasy.” But I certainly hope they’re a minority.

I look at books like “The Master and Margarita,” which to me is one of my top-five novels, not my top-three novels, not my top novel, and that blends politics and fantasy. And I kind of think “Well, yes, it would be commercially safer to not do what I did but then it wouldn’t be the book that I wanted to write.” And it’s a big commitment to write a novel, it’s four years of your life. Those years won’t be coming back. And you better be damned sure it’s a book you do want to write. You need to write it for yourself and not for the imagined sensitivity of certain critics and readers who won’t go there.

And I don’t believe it’s that unusual. I don’t think I’m that outlandish and I trust the majority of my readership to come along with me and to be moved by and hopefully to be entranced by what moves and entrances me. So I detected risk, but what’s art without risk? I think the answer is “anodyne.” And as you can hear from what I’m saying, I almost didn’t have a choice. I had to write “The Bone Clocks” the way it is. Unfortunately, I hope a minority of readers kind of won’t be able to digest part five but I have faith a majority will — and I hope time proves you right.

You write somewhere in the book that the future looks a lot like the past. Tell us what you mean by that?

I mean, most of what we do, we do because of electricity that has its origins in fossil fuels.

We’re having this conversation now is because of oil. I’m in a car that’s moving because of oil. I’m in North America because I flew in an airplane powered by oil. The clothes I wear were made in factories powered by oil, brought from China in container ships powered by oil, distributed in the UK and Ireland by trucks powered by oil. The food in my stomach was brought to the shops from the wholesalers all because of oil.

It was grown in the first place, whatever crop it was, thanks to oil as a means of turning oil into food — the pesticides, the fertilizers. It’s all about oil. And they’re not making any more of the stuff. And the reserves that are left are costing ever more quantities of oil to extract and it’s becoming ever more expensive.

Our civilization is magnificent: We can do things that even in the last 15 couldn’t have been imagined 100 years ago. It’s exponentially miraculous. I’m having a conversation on a smart phone that wouldn’t have existed 10 years ago. But, it’s all powered by technology —with the exception of nuclear fission, which has problems of its own as people in northeastern Japan can affirm. It’s all being powered by 1940s technology: oil-driven, fossil-fuel-driven power stations. And we do not own to this as a civilization and it’s on pace — it’s OK for me, I’m in my 40s, I’ll probably be OK by the end of it — but we are running up a terrible bill that our children and our grandchildren are going to have to pay.

So as I put my futurologist hat on and try to pre-construct a world set in the 2040s, I just wanted to, I have to do – Holly’s still alive then — to show the world she’s living in. And that is, I fear, what the world may well look like.

On that cheery note, my last question. You use music as an indicator of time and place and other things throughout the book. Talking Heads is a band that seems to work through this novel and others. I noticed you named a dog Zimbra [from the Talking Heads song, “I Zimbra”] near the end. Why do the Talking Heads keep coming back to you and your characters?

Oh wow. What a hip association. I hope David Byrne won’t mind me hanging onto his coat tails. But they’re in this book because most people who know about music will be able to relate to Talking Heads and the “Fear of Music” album: It’s so good, Jonathan Lethem wrote a book about it.

It sounds better now even than it did in the 1980s. It’s a tidy piece of work and it made an intelligent [reference] when Vinny gives Holly that record as a love gift in the early days of their brief courtship. It seemed like an intelligent choice. And there’s something relevant about the lyrical content as well. “Heaven” is a song about the ambiguous nature of heaven and the cyclical nature of eternity — that is eternity is kind of a trap rather than a broad expanse.

“I Zimbra” is a piece of music written in a made-up language. And communication and non-communication is one of the themes seeping through everything I write.