Recently, the author Andrew Solomon, while describing the Amazon reader reviews for his monumental book, “Far From the Tree: Parents, Children and the Search for Identity,” recounted that one reviewer objected to having to pay more that $9.99 for something that consisted of nothing more than electronic bits. “What about the 11 years of my life it took to write it?” Solomon asked plaintively. “What about the months my editor spent working on it?”

That’s a particularly egregious example of how writing remains a form of invisible — or at least translucent — labor. Solomon’s research for “Far From the Tree” encompassed, among other things, interviews with over 300 families; you can see every hour he spent on the book right there on the page. But no matter how infatuated our culture has become with the digital, we still have a hard time appreciating the value of immaterial creations. Consumers who demand that the price of e-books be slashed to less than half the hardcover list price reveal a belief that the work and expertise of a writer are worth less than a handful of paper and cardboard.

And, oh, that poor editor! (“It’s Nan Graham,” Solomon explained in an email. “And I value her more than gold and silver and precious stones.”) If most readers do grudgingly admit that someone must write the books they purchase, they are less willing to concede that the vocation of helping to bring someone else’s writing into the world has much merit. “You are uninformed in that technology is making many of the functions of editor and publisher obsolete,” one commenter posted to a New York Times story about the publishing industry. “Writers should need little to no editing when computers check spelling, etc.”

Even readers who claim to value non-automated editing have little sense of a editor’s actual responsibilities. The familiar grouse that “no one edits anymore” is usually followed by lamentations over the typos, grammatical errors and misspellings someone has found in traditionally published works. But correcting that kind of micro-mistake is the job of a copyeditor (or in some cases a proofreader), not the editor. So if the editor is not in charge of fixing “spelling, etc,” then what does an editor do?

There’s an expression (taken from “Hamlet”) most often used to refer to a good rule that is frequently broken: honored in the breach. But the phrase might be better deployed to describe a mission whose value we appreciate most when it fails. Like a counterterrorism operative, a good editor had done her best work when you don’t realize she’s done anything at all.

It is only when editors fail — as was the case with, say, the three New York Times editors who gave a pass to Alessandra Stanley’s now-infamous “Angry Black Woman” article on Shonda Rhimes — that their importance becomes evident. The same could be said for A.O. Scott’s much-discussed New York Times Magazine essay, “The Death of Adulthood in American Culture,” which was much-discussed in large part because the through lines of Scott’s argument were muddled by the deployment of too many examples that didn’t really fit his thesis. In both cases, a more culturally knowledgeable editor would have invisibly fixed the problem before the piece ever saw print.

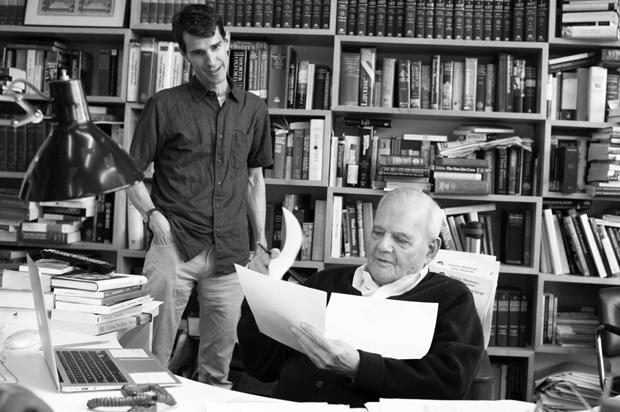

Martin Scorsese’s new film, “The Fifty-Year Argument” (currently being shown on HBO) is a rare tribute to another part of the editor’s job: Making writing happen in the first place. A documentary about the history of the venerable New York Review of Books, the film mostly focuses on the Review’s stellar contributors: Joan Didion, Zoe Heller, Daryl Pinckney, Daniel Mendelsohn, and many more. But interspersed with those interviews are quiet scenes that show the NYRB’s 85-year-old editor-in-chief, Robert Silvers, calling up writers and proposing assignments. It’s not great cinema, but it’s far more relevant to the Review’s stature than the more exciting archival footage of Norman Mailer shouting at the audience during a 1971 panel discussion on feminism.

“I needed him so much,” Didion tells the camera, recounting how Silvers had persuaded her to cover several Democratic and Republican conventions “not so much to walk me through it as to give me the confidence I could walk myself through it. … Bob involved me in writing about stuff I had no interest in.” As perverse as this strategy might sound, it does often work. That has been my own experience, particularly with Salon’s founding editor, David Talbot, who was always persuading me to tackle subjects (Michael Jackson) or to cover stories (a murder trial) that I considered off my beat; as a result I learned more than I would have if left to my own devices. Whatever the merits of my own stuff, the culture would be a lot poorer without Didion’s reporting on domestic politics. It shone in large part because, as someone who considered herself uninterested in the topic, she was able to bring a fresh, smart perspective to bear.

While this happens less often with books (it’s difficult to convince anyone to spend that much time working on a subject not of their own choosing), it does occur, albeit sometimes indirectly. James Baldwin’s “The Fire Next Time,” for example, although eventually published in book form, originated as an assignment to write about the Nation of Islam for Norman Podhoretz at Commentary. Editors also convince writers to bail on misbegotten projects and switch to more promising ones, or persuade them to reshape and recast books that aren’t working. Daniel Handler was struggling with a “mock-gothic novel for adults called ‘A Series of Unfortunate Events,'” when his agent sent his first and yet-unsold adult manuscript (“The Basic Eight” — highly recommended) to a children’s book editor, Susan Rich. She suggested he try writing for a younger audience, and Lemony Snicket was born.

Literary history celebrates many such cases, as well as instances when aggressive editorial “fat trimming” secured an author’s fame. The hierophant/editor Gordon Lish pared Raymond Carver’s short stories down to the bone, and even if Carver was not happy with this transformation, Lish’s scalpel played a major role in Carver’s exultation as the king of minimalism. Ezra Pound, in an unofficial capacity, performed the same wizardry on T.S. Eliot’s “The Waste Land.”

Maxwell Perkins, the editor who fought for (and with) such writers as Ernest Hemingway, F. Scott Fitzgerald and Thomas Wolfe, is regularly held up as the pinnacle of the editorial profession in years past. This praise is inevitably followed by the complaint that no one even tries to follow his example anymore. But then again, how would we know? It’s not a profession that attracts many spotlight hogs, and besides, the mystique of the solitary genius is so much more romantic than the reality that most good books are the result of a collaboration. I recently found myself sitting with three very talented, highly acclaimed novelists, so I asked them about their editors. “It amazes me,” said one. “They work so hard on our books, and then we get all the credit.” The other two writers nodded in agreement.

If editors like Perkins seem rare today, well, they were probably rare in the 1920s, as well. Not every writer gets the Maxwell Perkins treatment, but then again not every writer is F. Scott Fitzgerald. Furthermore, if every bad book can be held up as evidence that editors are falling down on their jobs, then every good book ought to be admitted as evidence to the contrary. (That includes every book from Gabriel Garcia Marquez, Alice Munro, Zadie Smith, Hilary Mantel and Don DeLillo, to name just five novelists.) It’s in the very nature of editing that the people who do it are doing it best when we forget all about them.

But surely the most endangered editorial role is, not coincidentally, also the most ineffable. In a recent post, Kent Anderson of the Scholarly Kitchen, a blog about academic publishing, reports that scientific and scholarly journals are now spoken of as if peer-reviewing were the only significant part of their editorial process: “one of the most important roles — that of the editor-in-chief or senior editor — seems to have been lost.” Of late, some journals have even been launched without any main editor at all; editorial and advisory boards, combined with peer review, have been deemed sufficient. There is no leader to be held personally accountable for the journal’s choices, and the publication loses something else, as well: vision, character, a personality all its own.

Anderson argues that in scholarly publishing — although the same goes for journalism and book publishing — a good editor-in-chief provides much that is crucial if also intangible. An EIC can be a martinet, a glad-hander, a guru or a sort of veiled prophet, only emerging from her office to utter baffling, oracular pronouncements. The best make their readers, contributors and staff feel like they’ve been invited to the greatest party ever, with the most scintillating, intelligent, profound and witty guests. They attract commercial authors who want to rub shoulders (or bindings) with literary greats, thereby helping to fund the continuing publication of literary greats, and they deploy their charm and expertise to get the best work out of major talents. Gifted younger editors want to work with them and in turn bring in new voices.

While the personality of a journalistic publication is usually clear to its readers, most book buyers are at best dimly aware of the distinct characters of the hundreds of large and small book publishing companies out there. (This includes smaller divisions of big presses, known as imprints, that are frequently named after the individual editors who run them.) Authors, booksellers and other industry types know exactly what each house stands for, but no publisher has had the equivalent of a Steve Jobs, someone whose role is to embody a coherent identity to both insiders and the public at large. For decades, this state of affairs has suited everyone just fine. Now that debates over what an e-book should cost — ultimately, a quarrel over the value of the labor invested in it by everyone other than the author — have gone public, that may no longer be enough.

Further reading

Margaret Sullivan, the New York Times’ public editor, on Alessandra Stanley’s article about Shonda Rhimes

A.O. Scott for the New York Times Magazine on “The Death of Adulthood in American Culture”

HBO’s page for Martin Scorsese’s “The Fifty-Year Argument”

Kent Anderson for the Scholarly Kitchen on “The Editor — A Vital Role We Barely Talk About Anymore”