After spending much of the past few years as one of the handful of companies who could justifiably regard the Great Recession as a blessing, the company that gave the world the Happy Meal, Ronald McDonald and those iconic "golden arches" was rudely reminded earlier this month of what life's been like for most everyone else: After posting some paltry numbers for third quarter revenue, income and earnings, McDonald's saw its stock drop by as much as 58 cents. And it sure doesn't look like the company's new slogan — "Lovin' Beats Hatin" — is going to be of much help.

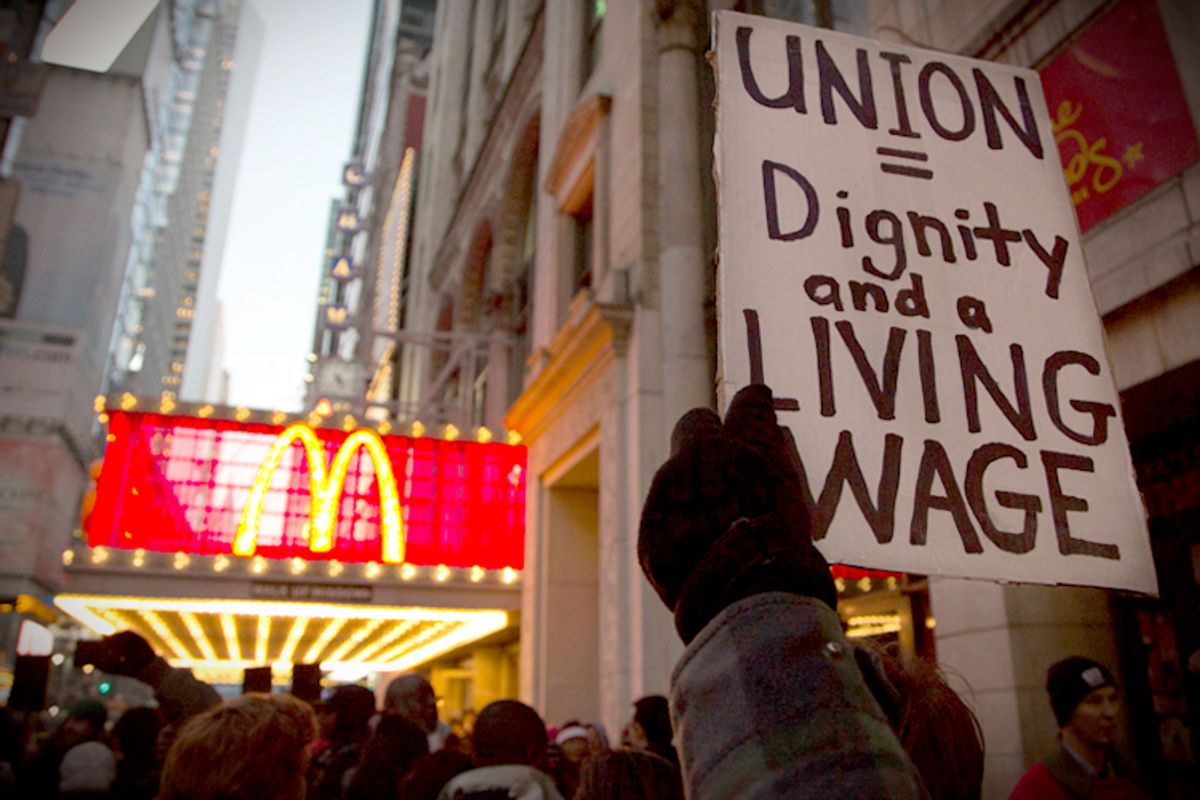

But while the rough patch being experienced right now by McDonald's and some other global fast-food titans is primarily due to rising pork prices, the stubborn resilience of the nationwide protest movement being waged by fast-food workers is certainly doing the industry no favors. With so many protestors no doubt feeling the exhaustion of running a multi-year campaign, and with the fast-food companies themselves in no position to dismiss their workforce's persistent (and popular) demands, you'd think now would be a time for leaders on both sides to start thinking about engaging in real negotiations.

At the very least, that's the question Harvard Law professor and On Labor contributor Ben Sachs has been raising as of late. And although the lack of union representation is one of the major points of contention between protestors and fast-food management, Sachs believes there may be a model for how negotiations can go forward nevertheless. Earlier this week, Salon called Sachs to discuss his idea and the fast-food workers movement in general. Our conversation is below and has been edited for clarity and length.

So let's set the stage for anyone who hasn't been keeping up with the fast-food protest movement. What's the state-of-play right now in the struggle between workers and these global fast-food corporations?

We’ve had a [fast-food workers] campaign that’s been going for almost two years. The central demands of the campaign are for an increase in wages, up to $15 an hour, and for a union...Part of the reason, in my view, that the campaign has gotten so much attention is that it’s raising issues that are pretty central to our economy and our society: wages, jobs, the future of the labor movement; all in some ways going to a broader theme of equality.

So the state of play is that we have a mobilized workforce making demands through public demonstrations. We have management responding through press releases and silence, but there’s no dialogue between the two sides, and that's what I see as sorely missing.

And that's why you've written a few posts at On Labor recommending both sides embrace a negotiation mechanism that you're calling a workers council. What will that look like?

In some ways, it’s just amazing — to me, anyway — that we have these huge national corporations with tens of thousands, sometimes millions of workers, and there’s literally no way for management to communicate to the workers as a group. That mechanism just doesn’t exist. When there’s a union we do have that mechanism, but we have unions in less than 7 percent of the private-sector today, so for the vast majority of people employed in the United States, there’s just no way for workers to talk to management.

That, in essence, is what a workers council [provides]. It’s a way for workers to elect representatives and to communicate through those representatives with management.

Some of the most successful companies in the world operate with workers councils. Volkswagen is a great example. The management at Volkswagen speaks about its workers councils in glowing terms. They use the phrase ‘constructive cooperation,’ that is to say, a workers council gives management and workers a way to be constructively cooperative with one another about the running of their operations.

It sounds like a very sensible idea. Common sense, even. So why don't McDonald's and the other big fast-food giants have workers councils already?

It's complicated. Part of the problem in the United States has been a legal problem. We have a labor statute which was drafted in 1935 to facilitate unions and, in facilitating unions, that statute sort of outlaws other forms of labor-management interaction and cooperation, which has made it difficult to set up workers councils.

The other answer is that, very often, unions have been opposed to workers councils and management has been opposed to workers councils, even though the workers themselves wanted one.

I can understand why management would be opposed, but can you tell me about why, historically, unions would be hesitant?

I think everyone would share your intuition [about management], but I think part of the reason to to think about Volkswagen and how corporations in other political and economic cultures [work] is to say that U.S. corporations should get enlightened about this question and understand that workers councils are actually in their best interests, too. A vehicle for constructive cooperation makes sense for both the management side and the labor side.

The reason that the labor [unions] have been an obstacle to workers councils is because there’s an association [between them and] company unions. There’s an association with the kinds of labor-management cooperation structures that were in place in the early 1930s, which were often a sham and were often a way management asserted even greater dominance over its workforce.

So there’s some remnants of skepticism of any kind of labor-management organization that’s not a traditional union, [and] that comes from the experience with company unions. (Just to be clear: We should not have those today, either! That is not what I’m advocating for.)

Sticking with the Volkswagen example, then, how should we interpret what happened earlier this year between Volkswagen, the UAW and those factory workers in Tennessee? Any reason to see it as a foreboding sign in regard to getting workers councils off the ground?

The salient fact about Volkswagen in Chattanooga, from this perspective, is that the workers council question was tied to the question of joining the UAW. The parties in Chattanooga believed, at least for a time, that the only way to have a workers council there was to first have the UAW organize the plant. The fight there was about the UAW, not about the workers councils.

What I’m suggesting for McDonalds is that they do a workers council now, that they don’t need to wait for the conclusion of a unionization campaign that workers may or may not ever get. This way, workers and the employer can sit down at this table and begin to talk about these issues together, rather than battling it out in the street.

Is there a specific potential future issue you're trying to anticipate with the workers council? Do you worry that the protest movement could fizzle out, or something like that, if it doesn't lead to a more concrete form of negotiations soon?

I don't think it makes any sense to have an indefinite protest movement when what is ultimately needed is negotiations. We need to create the forum for those negotiations to take place.

I don’t want to hazard a guess about what happens in two years if we don’t have a table; we’re going to need a table. Eventually, if the movement continues, if workers continue to mobilize, there’s going to be a moment when the two sides need to sit down and talk. And when that moment comes, I want to make sure we have the forum for those negotiations.

I want the negotiations to be democratic. I want the workers to have an elected representative voice to express their demands and negotiate with management. That’s part of the virtue of the idea of a workers council; and from management’s perspective, being able to engage productively with the workforce potentially brings of a lot of added value. It’s a much more productive resolution to this than just a continuing string of protests.

I should say: I am not in any sense advocating an end to the mobilization; you don’t replace the mobilization with the workers council. Workers need [mobilization]. Consumer support, political support and their own mobilization — that’s the source of their power. It’s just that we need a way of channeling that [mobilization] into constructive dialogue.

And to return to something you mentioned in the beginning of our conversation, about why these protests have gotten so much attention, what is it about the fast-food workers' demands that you think makes them resonate and makes this more important than a simple labor dispute within a particular industry?

Fast-food is emblematic of a lot of different sectors in the American economy. We have what [Boston University economics professor and head of the Department of Labor’s Wage and Hour Division] David Weil calls the fissured workplace, where the chains deny employment authority over the workforce and instead say that it’s the franchises that have that authority. That kind of fissured employment relation exists across a lot of the retail industry. (We see it in Über, for example.)

Fast-food is also emblematic in the sense that we see people working at extremely low wages — and by extremely low I mean not sufficient to support their families — so that people end up working full-time and yet still needing public benefits (which we see that not just in fast food but with Walmart employees, too). And then you layer on top of that the extreme difficulty of organizing traditional unions in all of these settings.

So the question is, what do we do? There’s no single answer; there’s no magic solution to all this stuff. What we ought to want to strive for is some mechanism that can, number one, increase economic and political equality in the country; and, number two, give workers a collective voice in the terms and conditions of their work lives. Workers councils are one possible way of moving forward, and you can do it in all of these setting. We could have a workers council at Walmart; we could have a workers council at Über; we could have a workers council at McDonald's.

Whether the workers councils would be the first step in something broader or the be-all and end-all remains to be seen, but what we know is that it would give workers who don’t have a collective voice in setting the terms and conditions of their work that kind of collective voice, and it would give management a way of engaging, as Volkswagen says, in constructive cooperation with their workforces.

Shares