Individual racism kills quickly and loudly. It’s used whips, nooses and guns to abruptly end black lives. But institutional racism kills slowly and quietly. It underfunds black schools, concentrates blacks in poor neighborhoods, limits black people’s economic opportunities, and packs black people into prisons. Institutional racism kills by making life harder for black people.

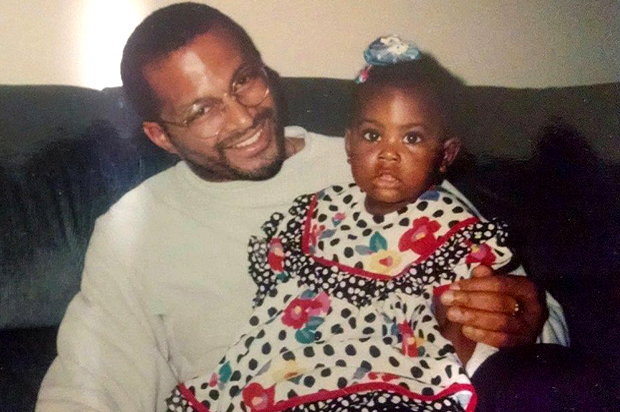

My cousin, Charles Goodridge, was a victim of both types of racism. His life was ultimately ended by a police officer’s bullets, but racism had already been killing him for a long time.

In a prior piece here at Salon, I said that I didn’t want to tell you about my cousin because I was afraid that if I did, you’d focus on his individual story instead of on an institutional crisis. I’m sharing his story now because I believe that it sheds light on the structural obstacles that all black Americans face.

On July 9, my cousin, an unarmed black man, was shot and killed by a police officer in Harris County, Texas. According to police, Charles had been evicted from his apartment but was spotted in one of the apartment complex’s common areas by Francisco Ruiz, an off-duty police officer who lived in the apartment complex and was working a second job as a security guard. According to police, Ruiz got his gun and handcuffs from his apartment and tried to arrest Charles for trespassing. Charles resisted and fled but Ruiz caught him and shot him twice in the stomach.

I believe that if Charles had been white, the officer who killed him would not have been so quick to arrest or shoot him. But that’s not the only way that racism killed my cousin. In fact, if it weren’t for years of institutional racism, Charles probably never would have been in the situation that sparked his deadly encounter with police in the first place.

Institutional racism started killing my cousin in 2005 when his employer of 10 years, Hewlett-Packard, transferred him from Boston to Houston with the promise of a promotion and a raise. While he was given a new title, he never received a raise. Things deteriorated from there until finally, in 2007, Charles filed a racial discrimination lawsuit against HP. He claimed that he was underpaid compared to his white co-workers, passed over for promotions, and that his supervisor called him and other black employees “boy.” He filed a second suit in 2008, alleging that he and other employees were not appropriately compensated for overtime.

Charles’ experience at HP is extremely common for black workers. In fact, racial discrimination lawsuits are the most common complaint brought against American employers every year. Blacks are routinely paid less, promoted last, and fired first. And while coroners don’t site “underpayment” as a cause of death, it certainly hastens our demise.

Charles’ cases ended in 2009 with a settlement that appears to have awarded him less money than his lawyer and left him jobless at the height of the recession. Despite his skills and experience, Charles was never able to find stable employment again. In this respect, Charles’ story is also tragically representative of that of many black Americans. The black unemployment rate is consistently double that of whites and, once unemployed, blacks remain unemployed for longer. The struggle with joblessness was, and is, slowly killing many black people, not just Charles.

Years of underemployment caught up to Charles. His savings dried up and, unable to make ends meet, he was forced out of his apartment. Charles’ experience with housing is also devastatingly common for black Americans. (Since blacks are underpaid while employed and more likely to lose their jobs, it should come as no surprise that, like Charles, black people are more likely to lose their homes because of financial hardships.)

So, on the night that he was killed, the fact that Charles’ presence in the apartment complex could be construed as some sort of violation was the result of a series of systemic injustices to which millions of black Americans are subjected every day. One structural problem (discrimination in the workplace), led to another structural problem (unemployment), which led to another structural problem (financial insolvency). He had once lived in the apartment complex where he was killed. In the past, the officer who killed him would have had no grounds to tell him to leave. But years of institutional racism changed that.

Other recent black victims of police violence have also suffered from institutional racism. Though it was a police chokehold that ultimately killed Eric Garner, institutional racism arrested him dozens of times and eventually led to him selling untaxed cigarettes to feed his family. And while police bullets ended Michael Brown’s life, institutional racism assigned him to live in a low-income neighborhood that was frequently patrolled by heavy-handed police.

Perhaps because it is so widespread and common, we have become desensitized to institutional racism. But If we want to create an equal and just society, we must be just as outraged at the commonplace, institutional racism that surrounds us every day as we are at the most shocking instances of individual racism. It’s important to hold individuals accountable for their actions. I want the man who killed my cousin to be held accountable. But I don’t want accountability to stop there. Systemic racism had been killing my cousin for a long time; that system must be held accountable as well.