“The Good Wife” has, for the entirety of its run, reveled in gray areas — the space in between absolute truth and absolute fiction, between innocence and guilt. In part that’s because the showrunners, Michelle and Robert King, seem drawn to the drama and humor of the middle ground — that space most of us live in most of the time, lofty ideals or basest desires aside. And in part that’s because its protagonists — the lawyers and politicians of Chicago — exist in a sphere that is almost entirely gray, while aping the rhetoric of the black-and-white. Voters don’t want to hear that crime enforcement is complicated; they want to hear that criminals are going to prison. Juries don’t want to untangle the threads of what it means to be complicit in our world; they want to rule whether a defendant is innocent or guilty.

That nuance is brought to bear with heartbreaking force in last night’s episode of “The Good Wife,” “The Trial,” where name partner Cary Agos of the newly minted law firm Florrick, Agos & Lockhart ends an episode of long deliberation by choosing to plead guilty for a crime he didn’t commit. With that, Cary takes a plea bargain for a four-year prison sentence, which will likely shake out to two years in prison. He’ll be a convicted felon for the rest of his life. He might still be able to practice law in Illinois, but with markedly less credibility; and that is, of course, if the myriad risks of prison don’t get to him first.

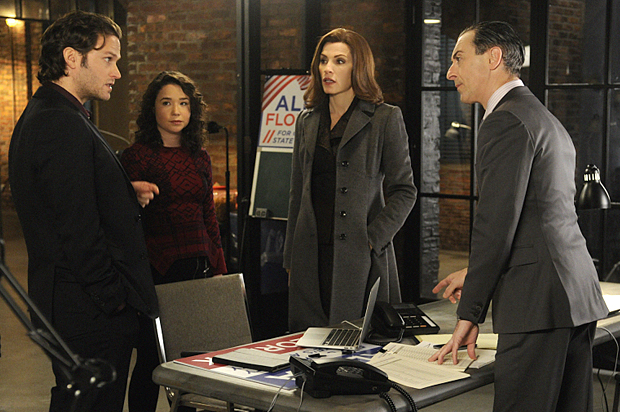

This half-season of “The Good Wife” has been a little inconsistent. “The Good Wife” is a show that’s always very enjoyable in the moment, thanks to fantastic directing and acting, as well as a writing style that privileges the present tense over either the past or the future. Above all, this is a show that is about getting through the day-to-day hustle of being a working person. Struggles with technology, parenting, HR, bureaucratic red tape, and the general absurdity of other people are “The Good Wife’s” bread-and-butter.

In this season, Cary’s prison plotline has come out of nowhere and persisted without a ton of explanation; the state’s attorney’s motives for arresting him weren’t totally clear, and their pursuit of him has felt both vindictive and scattered, as if they know they’re the bad guys but they keep forgetting why. It doesn’t totally feel like “The Good Wife’sa’ typical subtlety. On top of that, it’s gone on for a very long time. “The Trial” should have been a climactic episode; instead it feels a little like a letdown coming after “Sticky Content,” which moved a lot faster, and took a lot more risks, at least from a storytelling perspective.

To use just the most obvious example: In “Sticky Content,” Alicia discovers her husband is sleeping with another woman, and that knowledge impels her to make a move on her friend Finn Polmar. “The Trial” downshifts them back to small talk so fast it’s a little startling; it’s established that something “weird” happened, but it’s not even appreciably awkward. Alicia is not shown dealing with the fallout of Peter’s infidelity, either. The story literally ends up revolving around a poorly worded joke that Alicia writes out for her daughter. And while that is funny — because Julianna Margulies can sell anything, and the editing on this show makes even the barest inflections of irony hilarious — it’s not really a story; it’s fluff, used as a sideshow. (Longtime viewers will hear me when I say that any Grace plotline is immediately a weak one. Alicia’s younger child seems to exist mostly to facilitate frustrating story conventions. Which is my way of saying that she’s really annoying.)

So, purely as a 10-episode arc, I have my doubts about this season to date, and despite Matt Czuchry’s fantastic work as Cary in “The Trial,” these doubts weren’t assuaged.

But more generally — in terms of the themes that “The Good Wife” is playing with — this might be the most ambitious season yet. Something lingering at the back of my mind throughout this whole season is the uncomfortable truth that Cary is at least a little bit guilty: He’s not guilty of what the prosecution is charging him with, but he’s been helping a drug dealer make more and more money over the past several years, along with his partners at the law firm. It’s not outright illegal, no. But in a world where guilt and innocence are merely questions of rhetoric, our lawyer protagonists have found it pretty easy to ditch moral absolutes in favor of what’s most convenient.

One of the consistently most maddening things about the cast of “The Good Wife” is that all seem to be relatively good people who would never admit to standing for any particular good thing; all the more maddening because it bears a shocking resemblance to real life. Alicia is typically the show’s most vivid canvas for moral reckoning, as she’s got a strong value system she can barely articulate but often acts on. This season’s state’s attorney’s race is, for her, a moment to try to stand for something, even if she has no idea what that is most of the time.

For Cary, this is his first time in the show’s limelight. Up till now, we haven’t had much of a glimpse of his values, aside from winning as much as possible. He’s a man that feels things strongly; it’s telling, I think, that as he’s making up his mind in “The Trial,” he touches the shoulder of everyone on his legal team in a personal, quiet goodbye. He’s been half in love with Kalinda for years without articulating it, but he never really needed to, because it was pretty obvious to everyone else. Alicia is his sometime rival and sometime older sister; Diane is his mentor.

And he has to make one of the hardest decisions he’ll ever make in his life without any of them involved, because it’s a decision he alone can make: whether to accept a plea bargain, which makes him confess to something he didn’t do, or fight the case, which could lead him to a much harsher sentencing. Lemond Bishop, the drug dealer who got them into all this trouble in the first place, offers him a third option: flee the country and become his man in Europe.

The three choices are literally: white, black, gray. White: Do the “right” thing. Maintain your innocence. Go down with the ship. Black: Double down on your “guilt.” Take the free ticket. Become a criminal. Gray: Choose neither. Admit that you are guilty of something. Admit that this is terrible. Do your time. Never, hopefully, speak to Lemond Bishop again.

It’s very fitting to “The Good Wife” that Cary would choose the middle option, the option that most people take most of the time. Plea bargains are a controversial tool for prosecutors; Cary would know, as he’s brokered hundreds, maybe thousands, as both a private lawyer and an ASA.

But what “The Good Wife” often elides in its storytelling is the human toll of this flawed legal system; our lawyers are the ones playing the game, not paying the price. Cary’s trial flips that dynamic. For the first time, it feels like the legal decisions being made in the high-ceilinged conference rooms formerly of Lockhart Gardner actually matter. These aren’t just numbers; these are the numbers for this person, whom we know, whom we will have to watch go through this. Cary’s face in this episode — again, brilliantly played by Czuchry — is in slow collapse, from exhaustion and fear and paranoia and anger.

And his very intense struggle is contrasted, in “The Trial,” with a fascinating narrative framing device: distraction. Repeatedly, throughout the episode, Cary’s trial is depicted as something the major players are not fully paying attention to. The prosecutor, Geneva Pine, is sleeping with one of the witnesses, and her husband just walked into the gallery, so her mind is elsewhere. The judge is trying to get Neil Diamond tickets. One of the jurors has trouble understanding words when he’s stressed out. We, as people, have such limited abilities to see beyond our own dramas into another person’s. That’s the real tragedy, somehow. Cary’s defeat, when he admits it, is less about the cruelty of the world that would convict him, and more about its blatant, blank indifference.