One of the biggest challenges we were up against in getting the president to move was the conventional wisdom that coming out in support was still politically perilous. For some time now, national polls were showing support for the freedom to marry at greater than 50 percent. Yet shifting the conventional wisdom in D.C. is hard.

To help us with this task, we sought to line up a bipartisan dream team of pollsters. We needed validators who were respected enough by those on both sides of the aisle that they would draw the attention of political journalists, pundits, and ultimately the Obama campaign. We reached out to Joel Benenson, the Obama campaign’s lead pollster, and Jan van Lohuizen, the lead pollster for George W. Bush, asking them to analyze trends on the freedom to marry and write a joint memo that we’d release to the press. I honestly didn’t think either would say yes, given the public role we were asking them to play. But they both agreed. They’d evaluate publicly available polling since the late 1990s and write a memo on their findings.

On Wednesday, July 27, Benenson and van Lohuizen presented their findings to assembled media at the National Press Club, with Evan Wolfson providing context and talking about the path forward. The pollsters highlighted the fact that growth in support of this cause was historically remarkable; neither had seen support grow like this, from 27 percent in 1996 to a solid majority in 2011, on any other social issue. And, they argued, this wasn’t just a phenomenon of younger voters overwhelmingly supporting the freedom to marry. It also reflected a reevaluation by voters in nearly every cross-section of society they’d looked at: Democrats, Independents, and Republicans; people at all age levels; people in most religions; and so on.

They debunked the idea that our opponents would be more motivated to go to the polls because they cared much more, highlighting that “supporters of marriage for gay couples feel as strongly about the issue as opponents do, something that was not the case in the recent past.”

Finally, they emphasized that given the demographics, support would move in only one direction. “As Americans currently under the age of forty make up a greater percentage of the electorate, their views will come to dominate.”

The effect was exactly what we’d hoped. Politico ran a story titled “Bush, Obama Pollsters See ‘Dramatic’ Shift toward Same-Sex Marriage.” It began, “In a new polling memo intended to shape politicians’ decisions on the question of same-sex marriage, the top pollsters for Presidents George W. Bush and Barack Obama jointly argue that support for same-sex marriage is increasingly safe political ground and will in future years begin to ‘dominate’ the political landscape.”

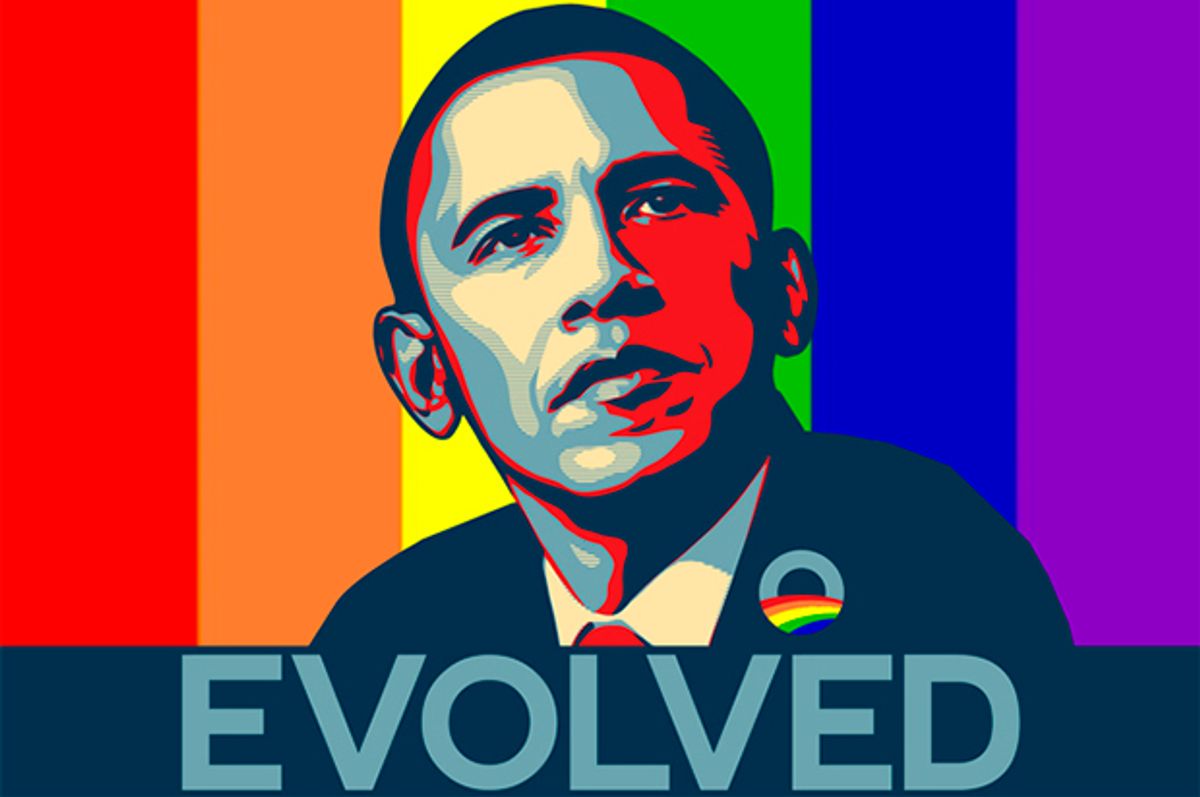

We followed up with an off-the-record media salon hosted by lesbian political commentator Hilary Rosen, featuring Joel Benenson and Evan, and attended by some of the top D.C. political reporters and columnists: Washington Post’s Ruth Marcus, National Journal’s Ron Brownstein, and a host of others. In a subsequent column entitled “The Good Politics of Gay Marriage,” Marcus wrote that “the data ought to give comfort that Obama would not commit political suicide were he to complete the evolution he clearly knows is inevitable. In the politics of 2011, survival of the fittest does not compel opposition to marriage equality.”

*

On December 14, Evan went to the White House for a second meeting with Valerie Jarrett. This time, he was full of thanks, for the administration’s embrace of heightened scrutiny and strong stand on the unconstitutionality of DOMA, and for backing the Respect for Marriage Act—the bill to repeal DOMA—when it was introduced earlier in the year. But Evan wasn’t there simply to congratulate. He was there to make the case that the president needed to finish the job and come out for marriage.

“With all respect, until you do it, you’re not going to get credit,” Evan told Jarrett.

She continued to push back, highlighting the president’s record on matters LGBT, including the bold actions on DOMA.

“You’re going to stop here?” Evan asked. “You won’t even get full credit for this amazingly wonderful thing.”

Evan shared the Benenson–van Lohuizen analysis and said that he believed strongly that supporting marriage would be to the president’s electoral advantage. He’d motivate younger voters who wanted to be with him but had become disillusioned over the last four years. And he was already too pro-gay to get the votes of those for whom opposition to marriage was a deciding issue.

He also said that, more than a year after the president said he was evolving, he was now coming across as inauthentic. That couldn’t be politically smart during the election season.

Jarrett bristled at the characterization of inauthenticity.

Evan then shifted to a hypothetical of how the president could come out for marriage if he decided to. “Would I love you to have the president come to some kind of Freedom to Marry event? Absolutely,” Evan said. “Or have me into the Oval Office and come out with a joint statement? Of course. But that’s not what you should do.” “What the president should do,” Evan asserted, “is sit down in an interview, in a conversational tone, with a reassuring message, and explain to the American people.”

Talk about the gay and lesbian couples in his life and the love and commitment they share, Evan suggested. And talk of the journey the president and first lady have taken and why they’ve resolved their own inner conflict in favor of the freedom to marry. This would be authentic, and it would model for the American people the journey that so many of them are on.

Jarrett listened carefully and engaged with Evan. Yet she didn’t show her cards on what she’d be encouraging the president to do.

The pollster memo and subsequent press made a splash, but as fall turned to winter in 2011 and the election grew closer, it still wasn’t at all clear if the president would come out in support prior to the election. The Democratic operatives I knew thought the president wouldn’t do it. After all, he was cautious by nature. And the word I got from one insider was that the campaign was most concerned about courting blue-collar white Democrats in rust belt states such as Ohio, Michigan, and Pennsylvania—not exactly our best demographic.

I, on the other hand, could not imagine how the president could go into the election still “evolving” on the issue. During a campaign, he wouldn’t be able to escape media interviews, debates, and the like. Would he really say, in a presidential debate with the Republican nominee, that nineteen months later he was still evolving? That would come off as not at all credible. Also, another powerful narrative was taking hold: that younger voters who were crucial to the 2008 victory and whom Obama needed in 2012 were disillusioned and might stay home rather than vote at all. Unlike any other issue, marriage equality appeared to inspire younger voters. So if the president enunciated a position of support before the election, it would help counter the cynicism that was seemingly at the heart of younger voters’ reticence to go to the polls. I believed he would move our way. I even wagered cocktails with a Huffington Post reporter that he would announce his support by the spring.

It seemed to me we needed another major public push. So I came up with an idea that wouldn’t target the president directly but would put pressure on him nonetheless: a freedom to marry plank in the platform ratified at the Democratic National Convention. I knew that most leading Democrats—including those in the LGBT community—would not want to put direct pressure on the president. Now was the time to rally around him and get him reelected, not push him to do more. But the platform was an indirect target; we were pushing the party, not the president. Of course, since the Clinton years, the party platform for the Democrats had been largely under the control of the Democratic nominee. The campaign would want to ensure it was in sync with the candidate’s position, at least on a high-profile issue such as this. So I knew it would be a pressure point.

I also knew that we could wage a serious, robust campaign that could make things difficult for the Obama campaign and the Democratic National Committee (DNC). There would be an official process for approving a platform. It would likely include field hearings around the country, and then a Platform Drafting Committee would make recommendations to a full Platform Committee, which in turn would recommend a platform for ratification to the 5,556 delegates. Polling showed that 70 percent of Democrats were with us, and I figured that, of the active Democrats who would be delegates to the convention, that number would be closer to 90 percent. Stopping an aggressive effort for a plank would come at real political cost; the Obama folks would really have to put their foot down on something the vast majority of delegates would want and something that younger voters overwhelmingly supported.

It was also the case that the Democratic National Convention was looking to be a real yawner. The press would be searching for any kind of controversy or drama. This could be it, and the press would eat it up.

My main hesitation was that it could hurt the president, whom I supported and who had done so much good for our cause. Freedom to Marry had done our own polling and electoral analysis, even using Obama’s lead pollster, but if the Obama campaign’s much more intricate research showed it would be harmful for him to come out in support—an argument that many people, including many in the gay community, were making—we’d be boxing him into an uncomfortable place. He’d have to either reject something that much of his base—gay and straight—cared a great deal about or do something that could hurt him electorally. Also, I’d lived through the 2004 presidential election, when the marriage movement was scapegoated for John Kerry’s loss. If Obama were to lose by a small margin to our Massachusetts nemesis, Mitt Romney, soon after Obama had endorsed marriage equality, I could see the finger-pointing coming at us again. That was nerve-racking.

I thought long and hard about it, I spoke with a few confidants, and Evan and I batted it around. I concluded that, based on everything I knew, it was politically smart, even necessary, for him to come out in support. During the campaign, he couldn’t hide from the question. And the evolving line was simply untenable. What’s more, he’d already taken so many proactive steps on LGBT equality that anyone who would say they were voting against him because he supported the freedom to marry would almost assuredly already be against him. And finally, my mission was to drive the cause forward; the president and his team would have enough firepower to push back if they wanted to. Evan concurred, and so we moved.

I figured this idea would be controversial enough that we wouldn’t be able to get elected national Democrats to sign up right away. So our plan was to create momentum for the plank on social media with online petitions, Facebook ads, and the like. We’d then go to elected Democrats beginning with our closest allies to sign them up as well as enlist couples, parents, clergy, and other good spokespeople to testify at field hearings throughout the country and talk to the media closer to the summer’s official platform meetings. We’d use multiple pressure points on those serving on the committees working on the platform, and then target individual delegates through a variety of means, building a drumbeat up to the convention.

Evan gave Valerie Jarrett and Brian Bond a simple heads-up that we were launching this effort. These were our friends whom we wanted to push, not our antagonists.

On February 13, we launched the campaign, which we called “Democrats: Say I Do!” We released specific platform language that we hoped to see adopted and got a few news stories, mainly in the LGBT press, about the effort.

Our slow-build plan was immediately overtaken by events. That night, Chris Geidner, a reporter with MetroWeekly, a D.C. LGBT newspaper, reached out to House Democratic Leader Nancy Pelosi’s office and asked if the leader supported the initiative. Her staffer contacted us to learn more and let us know that the leader did support it and was likely to say so publicly. The next evening, Geidner ran a short piece that quoted her spokesman as saying, “Leader Pelosi supports this language.” This was huge: Pelosi was disciplined and took seriously her role as a party leader. To have her on board would signal to others that this was an acceptable position to take.

The following week, the Obama campaign announced a list of thirty-five co-chairs of the campaign. Nearly everyone on the list—from Massachusetts Governor Deval Patrick to Los Angeles Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa, California Attorney General Kamala Harris, and New Hampshire Senator Jeanne Shaheen—was an outspoken supporter of the freedom to marry. This was a perfect list to mine and get as many as possible to take a stand in support of the marriage plank and then release that to the press.

I reached out to Senator Shaheen’s staff, whom I’d gotten to know well through the marriage campaign in New Hampshire. I knew they’d felt as though she’d never gotten the kind of recognition she deserved for her leadership on marriage. That, combined with her importance as a senior lawmaker from a swing state, made her an attractive and potentially motivated first senator to embrace the platform initiative. She was in, enthusiastically.

“If we look historically at the Democratic platform,” Shaheen told Huffington Post after we announced her support, “it has really been a vision document for where we’d like to go in the Democratic Party. Certainly I think this is a place where most of us believe we need to encourage the Democratic Party to go.” There was no question that now this was going to turn up the heat on the White House and the campaign.

Chris Johnson, a reporter with the LGBT publication the Washington Blade, saw the power of this story and reached out to all of Shaheen’s Democratic colleagues in the Senate to ask them if they, like Shaheen, supported the marriage plank. The subtext was, do you want to be left off a list when it goes public?

We piggybacked onto the Blade effort, making the case to senators, sharing the plank language, and telling them that the Blade would soon be calling and writing a story listing senators in support.

On Friday, March 2, the Blade ran its story. Titled “22 U.S. Senators Call for Marriage Equality Plank in Dem Platform,” the Blade explained that it had solicited written statements from all fifty-three Democratic senators and had received twenty-two in support. It quoted from each. John Kerry wrote, “I think this is an historic moment for the Democratic Party in our commitment to equal opportunity and our opposition to discrimination.” Senator Chris Coons of Delaware said simply, “Of course marriage equality should be a part of the Democratic Party platform.”

Los Angeles Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa had been appointed the chair of the Democratic National Convention. One of the first questions he was asked was whether he supported the plank initiative. A stalwart support, his answer was that he did.

The week of March 5, both Obama campaign manager Jim Messina and White House Press Secretary Jay Carney were asked at press briefings about the initiative. Neither had much to say, but I loved it. There was no way the White House and Obama campaign weren’t paying attention now. We needed to keep the pressure and momentum going.

The following week, Huffington Post ran a long feature article on its home page about the pickle the Obama campaign was in with the platform initiative. Titled “Barack Obama, Gay Rights Groups Struggle over Democratic Platform,” the article spoke of conversations with “more than a dozen party officials and activists.” It said, “The wave of support to make it a component of his convention has both surprised aides and set off a private push to keep emotions and expectations in check.” It spoke of the campaign and the DNC “searching for ways to split the difference: showing support for equality but stopping short of a full-fledged endorsement.” The article cited sources who said “that the DNC has been asking advocates for patience, worried that more sweeping platform language would put the president in an awkward bind.”

We’d created a legitimate controversy, and the White House and campaign were coming to know that there would be a cost for the party—and the president—to not embrace the freedom to marry.

On March 25, 2012, I was watching the Sunday morning talk shows, and my ears perked up when I saw George Stephanopoulos turn to the platform initiative as he interviewed Obama senior advisor David Plouffe. Several months before, I had heard Stephanopoulos give a talk, and in response to a question, he’d said he seriously doubted that the president would come out in support of marriage prior to the election.

“I want to show the first sentence right there,” Stephanopoulos said to Plouffe, showing him the language we’d developed. “It says ‘the Democratic Party supports the full inclusion of all families in the life of our nation, with equal respect, responsibility, and protection under the law, including the freedom to marry.’ Now, the president has said he’s evolving on the issue of gay marriage, but he’s still opposed. Does that mean that he’s going to fight the inclusion of this plank in the Democratic platform?”

Plouffe was extraordinarily astute at staying on message and avoiding questions he didn’t want to answer. “We don’t even have a platform committee yet, much less a platform,” he responded. He then went on to focus on the differences between the president’s record and the Republicans’ on all matters of equality for the LGBT community.

Stephanopoulos kept pushing. “Why can’t he say what he believes on this issue?”

“He has said what he believed,” Plouffe responded, in a very unconvincing way. “As he said, it’s a very—this is a very important issue. It’s a profound issue. He’s spoken to this, you know, at—with great detail. I don’t have anything to add to that.”

This exchange only confirmed this story had serious legs. We needed to keep pushing.

I reached out to Steve Grossman, who was the chair of the DNC under Bill Clinton and was now the elected treasurer of Massachusetts. Steve had been a tireless supporter during the Massachusetts marriage campaign, and now I asked him to sign on to our effort and to enlist other former DNC chairs.

Steve knew the campaign wouldn’t be crazy about it, but he said, “This is the right thing to do.” He’d be happy to help and agreed to reach out to a list of former chairs. By April 4, we’d lined up four of them: recently retired chair Howard Dean as well as Clinton DNC chairs Don Fowler and David Wilhelm joined Steve in calling for a marriage plank. Steve penned an op-ed in the Capitol Hill newspaper, The Hill, explaining his reasoning. “From my vantage point,” Steve wrote, “today’s most crucial civil and human rights battle is how we treat our gay, lesbian, bisexual and transgender citizens. Doing the right thing here is at the core of what our Party should stand for. That’s why I am joining Freedom to Marry, 22 Democratic senators, Leader Nancy Pelosi, and more than 35,000 Americans in urging the Party to include a freedom-to-marry plank in the platform that will be ratified at the Democratic National Convention in Charlotte this September.”

*

On Sunday morning, May 6, the phone at Michael Lombardo and Sonny Ward’s home rang very early. Sonny turned over in bed and saw that it was his mother calling from Mississippi. She must have forgotten that Los Angeles is two hours earlier, Sonny thought. So he let it ring. When he saw the voice mail hit, he picked it up to listen.

“Your aunt Linda just called,” Sonny’s mother said excitedly. Linda had told her she’d been watching "Meet the Press" and Joe Biden had been on. The vice president had been talking about Mike and Sonny, Linda had said.

Sonny was sure it was a mix-up, a classic crazy story that seemed to happen often in his home state of Mississippi, where his mother and aunt lived. His mother knew they had hosted the vice president, and she’d shared the news with the family. Through some version of the telephone game, word must have come back that Biden had talked about them on national TV.

After listening to the message, Sonny couldn’t fall back to sleep so he got out of bed, went online, and found the "Meet the Press" transcript. He scrolled through the conversation to a part about marriage equality.

DAVID GREGORY: You know, the president has said that his views on gay marriage, on same-sex marriage, have evolved. But he’s opposed to it. You’re opposed to it. Have your views evolved?

VICE PRESIDENT BIDEN: Look—I just think—that—the good news is that as more and more Americans come to understand what this is all about is a simple proposition. Who do you love? Who do you love? And will you be loyal to the person you love? And that’s what people are finding out is what—what all marriages, at their root, are about. Whe—whether they’re—marriages of lesbians or gay men or heterosexuals.

DAVID GREGORY: Is that what you believe now? Are you—

VICE PRESIDENT BIDEN: That’s what I believe.

DAVID GREGORY: And you’re comfortable with same-sex marriage VICE PRESIDENT BIDEN: I—I—look, I am vice president of the United States of America. The president sets the policy. I am absolutely comfortable with the fact that men marrying men, women marrying women, and heterosexual men and women marrying one another are entitled to the same exact rights, all the civil rights, all the civil liberties. And quite frankly, I don’t see much of a distinction— beyond that.

To Sonny, it sounded so much like what Biden had said at their home a couple weeks before. Biden even gave the same shout-out to Will and Grace, saying that it “probably did more to educate the American public than almost anything anybody’s ever done so far.” Sonny kept reading.

VICE PRESIDENT BIDEN: I—I was with—speaking to a group of gay leaders in—in Los Angeles—LA—two, two weeks ago. And one gentleman looked at me in the question period and said, “Let me ask you, how do you feel about us?” And I had just walked into the back door of this gay couple and they’re with their two adopted children. And I turned to the man who owned the house. I said, “What did I do when I walked in?” He said, “You walked right to my children. They were seven and five, giving you flowers.” And I said, “I wish every American could see the look of love those kids had in their eyes for you guys. And they wouldn’t have any doubt about what this is about.”

Sonny was shaking and had goose bumps. Aunt Linda was right; the vice president was talking about their family on national TV.

Biden had seemed so real, so genuine with them. He had mailed photos to them after the event and signed the one to Josie, “Next time we’ll play out in the back yard,” referring to her offer of playing tag. The fact that they’d really had this big impact and he was talking about their family was one of the craziest and most powerful things he’d ever experienced in his life. Tears flooded his eyes.

I hadn’t watched "Meet the Press" that morning, but as soon as the Biden interview aired, I was barraged with e-mails about what Biden had said. I read the transcript carefully, and while Biden hadn’t said explicitly that he supported marriage for same-sex couples, the meaning was clear and it was certainly far closer than the careful words the president had always used. I talked with Evan Wolfson about what to say, and not surprisingly to me, he wanted to be assertive, thanking Biden for his support. So we quickly put out a statement from Evan: “The personal and thoughtful way [Biden] has spoken about his coming to support the freedom to marry reflects the same journey that a majority of Americans have now made as they’ve gotten to know gay families, opened their hearts and changed their minds. President Obama should join the Vice President, former Presidents Clinton and Carter, former Vice Presidents Gore and Cheney, Laura Bush, and so many others in forthright support for the freedom to marry.”

The White House immediately went into full damage control. “The vice president was saying what the president has said previously—that committed and loving same-sex couples deserve the same rights and protections enjoyed by all Americans, and that we oppose any effort to roll back those rights.” But in fact, everyone knew he’d gone further.

Later that day, the New York Times decided it. Its headline was “A Scramble as Biden Backs Same-Sex Marriage.” This was huge; it wasn’t just Freedom to Marry asserting that the VP backed marriage. It was now the New York Times.

At the White House daily press briefing on Monday, spokesman Jay Carney was bombarded with questions. Carney’s position was firm; Biden had said nothing new, and the president didn’t have anything new to say. Adding to the White House challenge was Education Secretary Arne Duncan’s definitive statement in response to a question on the MSNBC morning show Morning Joe that he supported the freedom to marry. ABC News’s Jake Tapper questioned Carney especially aggressively, stating that he didn’t “want to hear the same talking points 15 times in a row” about the president’s record on gay rights. After the briefing, Tapper said on the air, “Probably his mind has been made up, [so] why not just come out and say it and let voters decide? It seems—it seems cynical to hide this until after the election.”

That same day, we announced that Caroline Kennedy—one of the crucial early supporters of President Obama’s campaign in 2008 and co-chair of Obama’s search committee for vice president—had joined the campaign to call on a marriage plank in the Democratic Party platform. Sean Eldridge had reached out to her, and she was proud to stand with us.

*

On Wednesday morning, May 9, Evan called me and told me that he’d gotten a call from Brian Bond at the White House. The president would be making an announcement that day, Brian had told Evan. He wouldn’t tell Evan what it was, but it had to be about marriage. We immediately prepped a statement to release if the president did what we hoped, and we flipped on the television in our conference room in the office. In the early afternoon, I joined Evan and others on our staff in front of the TV as Diane Sawyer and George Stephanopoulos interrupted the scheduled show for an ABC News Special Report.

“This is an historic political and cultural moment in this country,” Sawyer said.

They went to Good Morning America anchor Robin Roberts, showing an excerpt from a longer taped interview that would be running later that night. Roberts was seated with the president face to face in the White House as the president spoke:

Well you know, I have to tell you, as I’ve said, I’ve—I’ve been going through an evolution on this issue. I’ve always been adamant that gay and lesbian Americans should be treated fairly and equally. And that’s why in addition to everything we’ve done in this administration, rolling back Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell so that you know, outstanding Americans can serve our country. Whether it’s no longer defending the Defense Against Marriage Act, which tried to federalize what has historically been state law.

I’ve stood on the side of broader equality for the LGBT community. And I had hesitated on gay marriage—in part, because I thought civil unions would be sufficient. That was something that would give people hospital visitation rights and other elements that we take for granted. And I was sensitive to the fact that for a lot of people, you know, the—the word marriage was something that evokes very powerful traditions, religious beliefs, and so forth.

But I have to tell you that over the course of several years, as I talk to friends and family and neighbors. When I think about members of my own staff who are incredibly committed, in monogamous relationships, same-sex relationships, who are raising kids together. When I think about those soldiers or airmen or marines or sailors who are out there fighting on my behalf and yet, feel constrained, even now that Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell is gone, because they’re not able to commit themselves in a marriage.

At a certain point, I’ve just concluded that for me personally, it is important for me to go ahead and affirm that I think same-sex couples should be able to get married.

I looked over at Evan and for the first time since I’d worked for Freedom to Marry, I could tell he was deeply, profoundly touched.

For me, I had several reactions. On a tactical, professional level as an advocate, I felt really great about the effort we’d waged to get the president on board before Election Day. There were many naysayers; nearly everyone I spoke to told me they thought he’d never come around before the election. Others were angry that we were even trying, concerned that we were hurting the president’s chances for reelection. So I felt vindicated in taking this risk and driving hard. I also felt that, with the platform initiative in particular, we’d run a really great campaign.

I also was gratified to see the president talk about the freedom to marry using the messaging frame that we had developed and that Evan had, in one of his meetings with Valerie Jarrett, recommended the president use when this time came. In a relaxed, one-on-one conversation, Obama spoke of the gay and lesbian couples in his life and of their love and commitment. He talked of how he wanted to be a good role model for his children. He spoke of Christ and the lessons of his faith, talking of how it comes down to the Golden Rule for him. This would reverberate around the country in a big way.

On a deeper and more personal level, I had an abiding feeling of peace, this feeling deep inside of myself that I as a gay man was okay, was a full citizen and a full human being in this country. The president is one man, but the presidency represents more than anything else the official voice of the nation, and I felt, in a profound way, as a gay man living in America, that all was all right.

ABC News went back to Sawyer and Stephanopoulos. Stephanopoulos talked of how there were many people within the White House who didn’t want to see this happen before the election. “But,” he continued, “he was forced into a bit of a corner.” He talked of Biden’s comments and the fact that the president would be getting questioned until the election. “And probably the big key,” Stephanopoulos concluded, was that “already his convention chairman, the Democratic leader in the House Nancy Pelosi, [and] a majority of Democrats were trying to put into the platform at the Democratic convention support for gay marriage. So the president [was] also facing a big fight at his convention that he did not want to have.”

That was great to hear, from one of Bill Clinton's former top operatives, someone who had his ear to the ground and knew how D.C. and the White House operated better than just about anyone else.

Excerpted from "Winning Marriage" by Marc Solomon. Published by ForeEdge, an imprint of the University Press of New England. Copyright © 2014 by Marc Solomon. Reprinted with permission of the publisher. All rights reserved.

Shares