On December 3, just hours after a New York grand jury refused to indict Officer Daniel Pantaleo for the murder of Eric Garner, hundreds of protesters took to the streets of Washington, D.C., to raise their voices in anger at yet another police murder of yet another unarmed black man.

One young black woman, speaking to a crowd blockading the intersection of 18th and Columbia, confronted white and middle-class allies who had expressed discomfort with the tenor and tactics of that night’s march. Here’s what she told them:

“I don’t have to censor myself to make you comfortable. If you haven’t made anyone uncomfortable by what you have to say, then you aren’t being real. You’re not telling the truth. I’m not here for respectability politics. I don’t give a shit. What I care about are my black people.”

With megaphones in hand and their bodies in the streets, these protesters rejected respectability to articulate a new mode of direct-action politics.

Two days later, I joined a crowd roughly 500 strong as it left D.C.’s Chinatown to march in a broad circuit, shutting down major intersections throughout the city. Streaming through the streets around suddenly gridlocked traffic, we were able to talk to people in their cars. Some honked in support. Others honked in anger. Some high-fived us, others flipped us off — and a few tried to run us over. But, a surprising number seemed happy to have been caught up in something larger than themselves; swept up in something more real and important than whatever destination they had once been rushing off to. Nonetheless, through confrontation and disruption, we would make certain that people heard us even if many weren’t yet willing to listen.

The very act of blockading traffic with one’s body demands a certain liberation from the stifling constraints of respectability. In Ta-Nehesi Coates’s memorable phrase, the politics of respectability is “the politics of changing the subject” from police killings of unarmed black men to the behavior of black victims of police brutality.

As a politics, respectability has long shaped negotiations across the color line. In exchange for a promise to morally police the behavior of poor and working-class black populations, potential white allies validate the leadership of middle-class and elite African-Americans. It also marginalizes those not willing to check their anger, or those who don’t (or refuse to) use proper language to express that anger. In effect, the politics of respectability accepts the exclusion of those deemed unrespectable from the protections of first-class citizenship.

This strategy originally developed alongside the advance of Jim Crow at the end of the 19th century. Respectability politics publicly accepted the principles of disfranchisement and segregation and sought to redraw the racial exclusions of the new Jim Crow order along the lines of class and gender instead. In the face of an implacable white supremacy, it represented an attempt on the part of black elites to preserve some measure of political power by trying to convert white paternalism into a genuine interracial politics. When confronted with disfranchisement in 1899, Georgia’s black leadership declared themselves willing to defend the purity of the ballot against “ignorant black voters” just so long as those restrictions applied to black and white alike. In so doing, they attempted to forge an alliance of black and white elites to uplift the unrespectable, unwashed masses of both races.

However, these sorts of negotiations across the color line have always been problematic. For one, those white allies are in no way obligated to reciprocate. Even worse, this politics of respectability powerfully reinforces racist stereotypes of black depravity and criminality, justifying the murders of Trayvon Martin, Michael Brown and Eric Garner. As unrespectable black men, they were asking for it.

Earlier in the 20th century, this same discourse encouraged black elites to defend both disfranchisement and segregation as a means of eliminating the “unqualified” from politics and the “unrespectable” from public space. Some even urged the formation of interracial lynch mobs to hunt suspected black criminals, whose failure to conform to middle-class standards of respectability they felt endangered the reputation of the race.

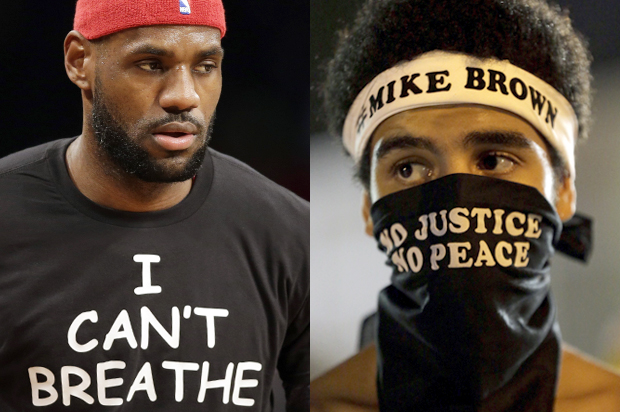

Over the course of my march through the streets of D.C. it became evident that the rupture with respectability politics had begun to create a space – even if momentarily – for a new kind of politics. Indeed, one of the most popular chants of the evening was “We Shut Shit Down.” The crowd also chanted “If We Can’t Breathe, You Can’t Breathe!,” words that carried the promise of retaliation, of pushing back, of not turning the other cheek, of resistance. Another call and response made this threat of retaliation even more explicit. It began with a demand: “What do you want? Justice! When do you want it? Now!” And ended with a threat: “And if we don’t get it? Shut it down! Shut it down!”

This was not an exercise in race relations, nor was it an attempt to convince a broader audience that black victims of police murder were deserving of help and charity. It was a demand to potential allies that they listen to black anger and act in solidarity. This rise of direct-action politics is directly linked to the failure of the power of respectability to inhibit protest.

This is not a new story. It was the collapse of respectability politics in the aftermath of the Atlanta Race Riot of 1906 that opened the space necessary for black voters in Atlanta to embrace a more oppositional politics. At the nadir of Jim Crow, the city’s black elites embraced respectability as a shield to defend themselves against both white supremacist violence and the worst indignities of segregation. However, the partisans of that year’s fiercely contested gubernatorial race whipped white supremacist voters into a frenzy, with each candidate campaigning on how best to disfranchise black Georgians. In late September 1906, a month after the election, white mobs went on a three-day rampage, murdering 25 black Atlantans. The pretext was a fictional black crime wave that had been fabricated by supporters of incoming governor Hoke Smith. While the black “criminal class” was the one supposedly responsible for Atlanta’s crime, the overwhelming majority of the victims were precisely those members of the black middle class who had embraced respectability as a shield against such violence. A morally upright life and a promise to “police” black criminals had not protected them.

In the aftermath of the riot, a section of Atlanta’s black leadership rejected the politics of respectability in order to embrace a more oppositional stance toward the city’s white elites. In 1919, the fighting grassroots of the early NAACP organized a voting bloc powerful enough to force the city to build Booker T. Washington High School, the city’s first publicly funded high school for black students. After years of being asked to vote for municipal bonds to build schools their children could never attend, black voters exploited a loophole in the state’s disfranchisement laws to defeat three bond referenda over the course of 10 months. By holding the entire city budget hostage, they compelled the city fathers to invest $1.5 million in black public education. This marked a dramatic shift away from an earlier politics of respectability that once sought to convert white paternalism into a genuine interracial politics. This rejection of respectability provided a new cultural foundation for urban black politics upon which black Atlantans could finally contend – and not merely negotiate – for their rights.

Those protesting the murders of Michael Brown and Eric Garner have used their bodies to shut down the circulation of goods, people and services. Similarly, Atlanta’s black voters used their votes not as expressions of individual political choice but rather as an instrument of collective power they used to shut the city down in 1919.

Given the intransigence and impunity of police power in this country, we need to apply the lessons of Atlanta. We must use our votes like we are using our bodies, not to put yet another equivocating candidate in office to speak in our place, but rather to interrupt business as usual. We must learn to cast our votes like monkey wrenches into the gears of the municipal machinery, disrupting the regular functioning of cities, counties and states until our message is heard. If we can’t breathe, you can’t breathe.

Jay Driskell is assistant professor of U.S. history at Hood College in Frederick, Maryland. He is the author of “Schooling Jim Crow: The Fight for Atlanta’s Booker T. Washington High School and the Roots of Black Protest Politics.”